In part 1, we discussed "He said, she said" reporting. In part 2, we did a little philosophical analysis. We asked, "Will burning less coal in power plants save lives?" The key issue for government regulation of coal power is whether it's within the government's proper purpose of protecting people. Read the previous parts first. This is the conclusion.

Coal has fans and haters. Electricity has proponents and opponents. Progress in general can be divisive. Some people see potential, others see new dangers. Some see improvement, others see disruption. The potential, new dangers, improvement and disruption all exist. Many people reply that we have to compromise. But we don't.

Burning less coal not only won't protect people, it would hurt people. It's a huge mistake for the government to push for it.

Philosophy is important here because it's the field which addresses fundamental issues like progress and compromise. Compromise and limiting progress are popular bad philosophy. Those mistakes make it hard to clearly see the value of coal. Bad philosophy helps enable mistakes for specific issues like industrial progress, abortion, emotions, dating and parenting.

Coal is mistakenly seen as a compromise with substantial negatives because everyone expects and seeks out compromises. A compromise is an outcome where some problem wasn't solved; it's a partial solution. People think that's the best you can do. Better philosophy explains how genuine full solutions to life's problems can be possible and should be sought. (If you are interested in more about full solutions, look over my archives or ask here.)

Progress (including industrial and scientific progress) is not a compromise. Progress looks like a compromise because it brings with it new dangers. But people have misunderstood the human condition.

The human condition is one of infinite problems. This is a good thing. It means there is infinite improvement possible, life can always be better. Whenever you make life better, it raises new problems – new opportunities. There is no way to avoid problems. If you do nothing, you will die. If humanity tries to live a "sustainable" lifestyle indefinitely, everyone will die. A meteor or plague may come, or something else. The only defense against the unknown potential problems of the future, like new diseases, is progress. The more progress we make, the more we can increase our general purpose problem solving power, giving us a chance against new problems.

Progress brings new problems, but they were coming anyway. Since that isn't avoidable by any means, it isn't a downside. And it doesn't make life bad, it's part of a good active life.

In broad outline, coal electricity, like other progress, brings massive benefits and some new problems. It has transformed life for the better. If you selectively look at the dangers it has brought (e.g. radioactivity in the smoke created), those may seem scary, and coal can look like a compromise. But if you look in a more broad way, instead of selectively, you can see the massive dangers coal solves (like working yourself to death with manual labor), as well as that new dangers are a part of life whether we use coal or not (so coal isn't really to blame).

Examining specifics, electricity makes life better with features like electric lights, computers, phones, stoves, refrigerators and motors. Electric lights give you more usable time, effectively extending your life. Computers automate tasks, saving time and effectively extending human lives. Phones enable friendships that would otherwise be impossible, making life better. Stoves make cooking safer by not having to burn wood or dung (comparing to coal plants, remember smoke is a lot worse when it's right next to you). Refrigerators reduce food poisoning. Electric motors help with transportation and factories. Factories allow mass production, which allows you to have products cheaply (meaning you work fewer hours, effectively extending your life) which help make your life better – example products include medicines, safe portable foods, tools that let you work more effectively, and luxuries that people value.

The massive benefit to human life is a theme of progress, and should be kept in mind as the main issue. People are too eager to dismissively say, "Sure there are benefits, but why not do it in moderation? Let's look at the downsides." Selectively focusing on the downsides of progress, while glossing over the upsides of progress and the downsides of non-progress, results in a biased non-objective understanding of reality.

People are worried the oceans might rise. Some lowland areas may flood. So what? That's way better than dying of cholera like people did before industrial progress. If it were a compromise, it'd be a great deal. But why compromise? Thanks to having an industrial civilization, we are powerful enough to solve problems like increasing temperatures or rising ocean levels. We can build walls, fans, or air conditioning. We can put mirrors in space or moisture in the atmosphere to reflect light. We have a lot of options.

The problems from industrial progress are speculative potential problems. It wasn't long ago that we were warned about global cooling due to industrial progress. But even if they are right, an industrial civilization is so much more able to solve arbitrary problems than a non-industrial civilization. Problems are always a concern, and technologies like coal power plants give us much better ways to solve them, including ways unthinkable to a pre-industrial civilization.

By attacking coal power, the Obama administration is making a huge mistake. Rather than protect people, it's endangering the future. Rather than try to solve the problems associated with coal, Obama wants to avoid them. But there is no such thing as a problem-free technology. Coal alternatives have plenty of problems too.

When should we switch? When other technologies work better. The government, which ruined the cleanest power industry – nuclear – needs to stop micromanaging. People will buy stuff with no coal involved on their own when it's the best option for their lives. Instead, taxpayers work to better their lives and the government takes a cut and uses it to subsidize technologies that can't stand on their own, because the Obama administration thinks its smarter than the rest of us. Obama wants to control people rather than protect people.

(This post has some ideas inspired by the book The Beginning of Infinity. I recommend reading it.)

Elliot Temple

| Permalink

| Messages (0)

Bad Scholarship by Cato Institute

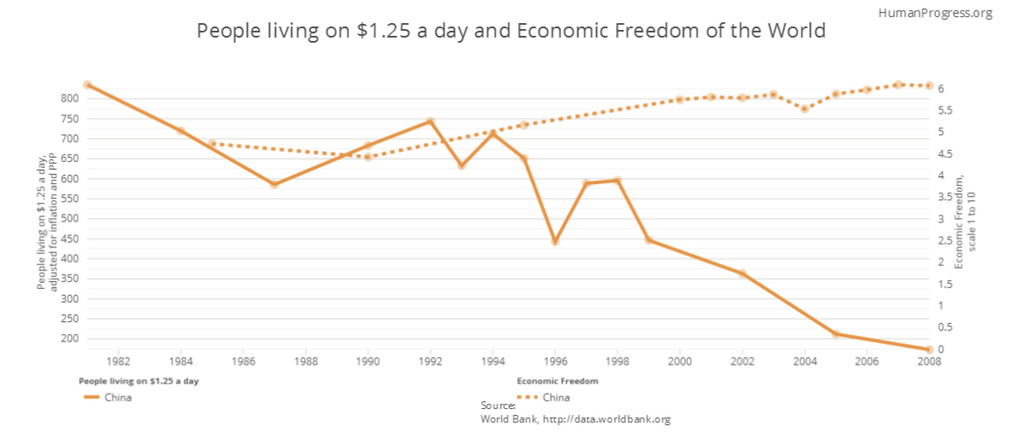

Cato tweeted a graph from their Human Progress project:

This graph is dishonest lying with statistics in several ways.

On the left, the numbers go from 200 to 800. These are millions of chinese people living in some definition of poverty. What happened to 0? They designed the graph so the change goes from above the top to bellow the bottom. A more accurate graph would show numbers from 0 up to China's population size (now around 1.35 billion). Cato cut off around 40% of the numbers on the left to make the graph look bigger, and leaving out 0 is a well known dirty trick.

On the right, it's even worse. The right side shows some kind of economic freedom number, from 1 to 10. But they numbered their graph from 0 to 6. They made the bottom actually go lower than is possible with their own metric. Why? To make the change from around 4.75 to 6 look way bigger than it is and to have it reach the top of the graph. A 6 out of 10 should not be at the very top of the graph! And the graph shouldn't go down to 0 when dealing with something that can only start at 1.

The graph title also suggests the graph has to do with economic freedom for the whole world by using the phrase "Economic Freedom of the World", but the graph is only about China (I think, going by how the two lines are both labelled as being for China only).

Overall, Cato is trying to show economic freedom going up and poverty going down. Eyeballing it, it looks to me like poverty went down more than economic freedom went up, using these metrics. Rather than discuss how correlated they are, or try to explain the right way to think about the issue, Cato created a grossly dishonest graph to mislead people. Cato is prioritizing shiny publicity over truth.

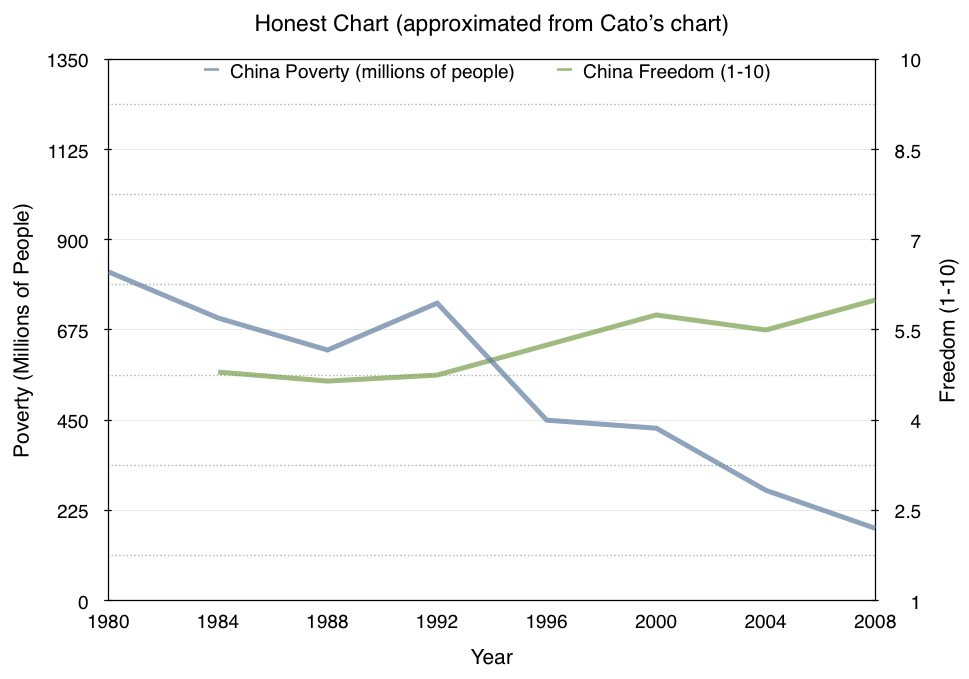

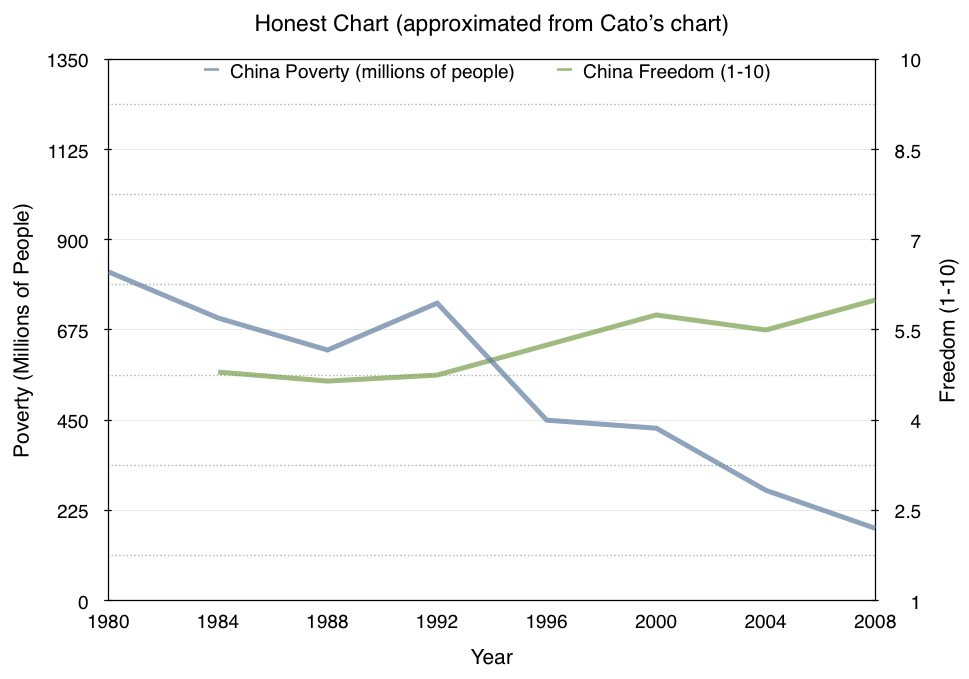

I also made a better chart so you can compare. For the data points, I eyeballed them from Cato's chart (not all of them, that's why it's smoother). Don't it super seriously as a fact about the world, I just wanted to see how it looked with the left and right axes fixed.

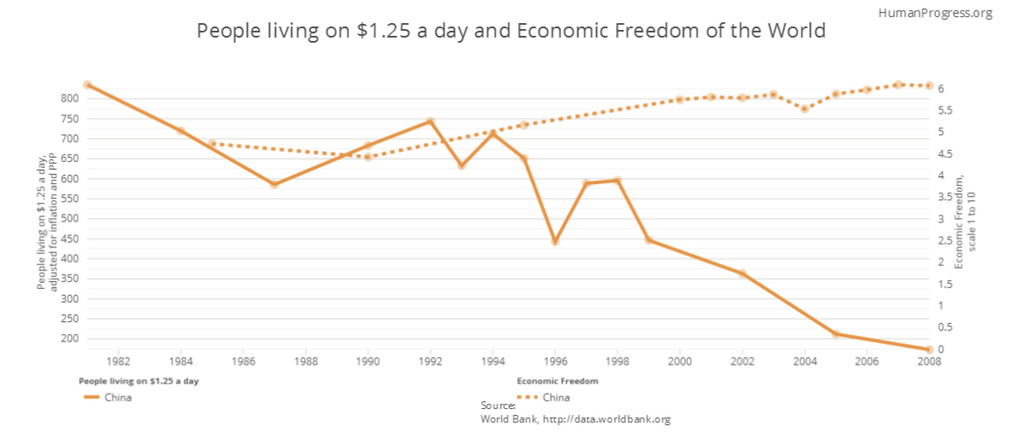

This graph is dishonest lying with statistics in several ways.

On the left, the numbers go from 200 to 800. These are millions of chinese people living in some definition of poverty. What happened to 0? They designed the graph so the change goes from above the top to bellow the bottom. A more accurate graph would show numbers from 0 up to China's population size (now around 1.35 billion). Cato cut off around 40% of the numbers on the left to make the graph look bigger, and leaving out 0 is a well known dirty trick.

On the right, it's even worse. The right side shows some kind of economic freedom number, from 1 to 10. But they numbered their graph from 0 to 6. They made the bottom actually go lower than is possible with their own metric. Why? To make the change from around 4.75 to 6 look way bigger than it is and to have it reach the top of the graph. A 6 out of 10 should not be at the very top of the graph! And the graph shouldn't go down to 0 when dealing with something that can only start at 1.

The graph title also suggests the graph has to do with economic freedom for the whole world by using the phrase "Economic Freedom of the World", but the graph is only about China (I think, going by how the two lines are both labelled as being for China only).

Overall, Cato is trying to show economic freedom going up and poverty going down. Eyeballing it, it looks to me like poverty went down more than economic freedom went up, using these metrics. Rather than discuss how correlated they are, or try to explain the right way to think about the issue, Cato created a grossly dishonest graph to mislead people. Cato is prioritizing shiny publicity over truth.

I also made a better chart so you can compare. For the data points, I eyeballed them from Cato's chart (not all of them, that's why it's smoother). Don't it super seriously as a fact about the world, I just wanted to see how it looked with the left and right axes fixed.

Elliot Temple

| Permalink

| Messages (0)

NYT Praises War

The Lack of Major Wars May Be Hurting Economic Growth

Not enough broken windows lately, The New York Times reports some supposed economists saying. Sort of. They claim what they mean is that people get fat and lazy during peace, and the threat of war keeps everyone on their toes better.

Maybe we should start using the death penalty on people who don't produce over $20,000 of wealth per year in order to better motivate them. What do you think?

Explanations of how destruction results in economic harm are easily available. (I suggest Economics in One Lesson.) Advocating war for its own sake, and own intrinsic benefits, is disgusting. The only legitimate purpose of war or other uses of force should be defense (including indirect defense).

These people are advocating death and destruction – literally – because of their half-baked theorizing. They don't think about human suffering, or how the equivalent of whipping people to motivate them might not work well in reality. It's ivory tower "intellectuals" at their worst.

Not enough broken windows lately, The New York Times reports some supposed economists saying. Sort of. They claim what they mean is that people get fat and lazy during peace, and the threat of war keeps everyone on their toes better.

Maybe we should start using the death penalty on people who don't produce over $20,000 of wealth per year in order to better motivate them. What do you think?

Explanations of how destruction results in economic harm are easily available. (I suggest Economics in One Lesson.) Advocating war for its own sake, and own intrinsic benefits, is disgusting. The only legitimate purpose of war or other uses of force should be defense (including indirect defense).

These people are advocating death and destruction – literally – because of their half-baked theorizing. They don't think about human suffering, or how the equivalent of whipping people to motivate them might not work well in reality. It's ivory tower "intellectuals" at their worst.

Elliot Temple

| Permalink

| Messages (0)

The New York Times Lying with Statistics

Tim Cook, Making Apple His Own from The New York Times:

A more meaningful comparison would compare the same time periods. It would also consider the number of employees of each company as well as their salaries. That would have made for better reporting.

The New York Times presents Microsoft's employee culture as being over 1900% more charitable than Apple's, but their own figures make the correct statistic 29%. By comparing absolute numbers from different time periods, they misled their audience by a factor of 65 in terms of the percent difference.

By comparison, Microsoft says that, on average, it donates $2 million a day in software to nonprofits, and its employees have donated over $1 billion, inclusive of the corporate match, since 1983. In the last two years, Apple employees have donated $50 million, including the match.The dishonest implication here is the Microsoft employees donate over 20 times as much money to charity, compared with Apple employees. Over $1 billion compared with $50 million. But the time periods compared are 31 years against 2 years. The per-year figures here (in millions) are over $32m/year for Microsoft against $25m/year for Apple, a much smaller difference.

A more meaningful comparison would compare the same time periods. It would also consider the number of employees of each company as well as their salaries. That would have made for better reporting.

The New York Times presents Microsoft's employee culture as being over 1900% more charitable than Apple's, but their own figures make the correct statistic 29%. By comparing absolute numbers from different time periods, they misled their audience by a factor of 65 in terms of the percent difference.

Elliot Temple

| Permalink

| Messages (0)

Bad Scholarship by Ari Armstrong

http://www.theobjectivestandard.com/2014/06/homosexuality-bible-rational-morality/

http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Deuteronomy+22%3A13-22&version=ASV

What the Bible actually says is she needs to be a virgin when they marry. If a man hates his wife and accuses her of shameful things and says she wasn't a virgin when they married, then she is to be stoned. (Unless it was a false accusation and she actually was a virgin when they married, in which case the man is fined and has to keep her as a wife. I'm unclear on how it's to be decided whether she was a virgin or not using a garment.)

Armstrong said if a women is hated by her husband and a non-virgin (now), then the Bible advocates her murder. But the Bible actually only advocates her murder if her husband hates her and she was a non-virgin when they got married. The difference is her husband's taking of her virginity doesn't count against her.

After finding this scholarship error, I decided to check the other four claims using Armstrong's own links. The witches, children cursing parents, blasphemers, and adultery ones are accurate. The worshipping other gods one is wrong.

http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Deuteronomy+13%3A6-10&version=KJV

This Bible passage is saying if a family member or friend tries to "secretly" "entice" you to "serve other gods", then don't do it and kill him. So it's specifically about people who worship other gods and try to convert you. Armstrong misrepresented it.

To be clear, in none of these cases do I agree with the Biblical position.

Two misrepresentations of the Bible out of six references is a really bad error rate (33%). And this is basic stuff. Did Armstrong click on the links he gave, and read them? I'm not even sure. I don't think Armstrong should tell people they "must discard" a Bible he misrepresents and misunderstands.

Armstrong claims to offer Objectivism as a rational alternative to the Bible. But bad scholarship is irrational. Reason demands using methods of scholarship that are good at avoiding error and finding the truth. Armstrong linked this on twitter. I've tweeted him back informing him of the problem, and will update my post if he fixes his mistakes.

The fact that the Bible advocates the murder of homosexuals (as well as the murder of “witches,” of those who worship other gods, of blasphemers, of children who “curse” their parents, of adulterers, and of non-virgins whose husbands hate them—among others) indicates that the Bible, far from being a guidebook for morality, is largely an absurd book of mindless and evil prohibitions and commandments rooted in nothing more than ancient superstitions.In the original, six of those claims about the Bible saying to murder people are linked with sources. One is non-virgins:

http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Deuteronomy+22%3A13-22&version=ASV

What the Bible actually says is she needs to be a virgin when they marry. If a man hates his wife and accuses her of shameful things and says she wasn't a virgin when they married, then she is to be stoned. (Unless it was a false accusation and she actually was a virgin when they married, in which case the man is fined and has to keep her as a wife. I'm unclear on how it's to be decided whether she was a virgin or not using a garment.)

Armstrong said if a women is hated by her husband and a non-virgin (now), then the Bible advocates her murder. But the Bible actually only advocates her murder if her husband hates her and she was a non-virgin when they got married. The difference is her husband's taking of her virginity doesn't count against her.

After finding this scholarship error, I decided to check the other four claims using Armstrong's own links. The witches, children cursing parents, blasphemers, and adultery ones are accurate. The worshipping other gods one is wrong.

http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Deuteronomy+13%3A6-10&version=KJV

This Bible passage is saying if a family member or friend tries to "secretly" "entice" you to "serve other gods", then don't do it and kill him. So it's specifically about people who worship other gods and try to convert you. Armstrong misrepresented it.

To be clear, in none of these cases do I agree with the Biblical position.

Two misrepresentations of the Bible out of six references is a really bad error rate (33%). And this is basic stuff. Did Armstrong click on the links he gave, and read them? I'm not even sure. I don't think Armstrong should tell people they "must discard" a Bible he misrepresents and misunderstands.

Armstrong claims to offer Objectivism as a rational alternative to the Bible. But bad scholarship is irrational. Reason demands using methods of scholarship that are good at avoiding error and finding the truth. Armstrong linked this on twitter. I've tweeted him back informing him of the problem, and will update my post if he fixes his mistakes.

Elliot Temple

| Permalink

| Messages (0)

Alex Epstein Scholarship Problem

Alex Epstein wrote:

Sourcing your assertion to someone else's unsourced assertion isn't scholarship. It's how lies spread.

I've investigated this topic. Several studies have been done about electronic device usage in U.S. households. However, none of them would be acceptable sources. All the ones I found have a large methodological error. For example:

There is an additional problem here. When the surveys use a specific list of devices, they change it over time. Today we would expect smartphones to be on the list. Thirty years ago, they would not have been. Changing the list of which devices count means the surveys from different years are not comparable because they measure different lists.

When you pretend what's being measured is "(consumer) electronic devices", then it would make sense to compare studies from different years, because they appear to measure the same thing. But really one survey is about list A and another survey from another year is about list B, and calling the two lists by the same name doesn't make them the same thing. Epstein's comparison between the present and thirty years ago, using two different surveys of two different things, is a mistake.

I informed Epstein of these scholarship errors and he did not fix them. He should not repeat unsourced claims from Youtube that are presumably based on misusing the readily available invalid research. The truth matters.

In the US, 30 years ago the average household had 3 electronic devices—today it has 25, overwhelmingly thanks to fossil fuels.For a source, he linked this youtube video from "Alphanr" (Alpha Natural Resources). It's titled "Did You Know" and has no description. It's 89 seconds long and packed full of factual claims including the one Epstein asserted, but lacks sources. It ends with a link to their website. Searching for "Did You Know" on the site to try to find extra details results in an error. Their site says, "Alpha is a leading global coal company and the world’s third largest metallurgical coal supplier". I doubt they have expertise at surveying household electronic device usage.

Sourcing your assertion to someone else's unsourced assertion isn't scholarship. It's how lies spread.

I've investigated this topic. Several studies have been done about electronic device usage in U.S. households. However, none of them would be acceptable sources. All the ones I found have a large methodological error. For example:

Of the 37 CE [Consumer Electronic] devices surveyed, the average U.S. household owns 24, the same number as last year, and spent $961 on consumer electronics over the past 12 months, down more than $200 from last year. The average adult individually reports spending $552 on CE in the past 12 months, down $100.They are surveying how many devices U.S. households have from a list of 37 devices. That list is incomplete. The number of devices from the list that a household has is different than the number of consumer electronic devices the household has.

There is an additional problem here. When the surveys use a specific list of devices, they change it over time. Today we would expect smartphones to be on the list. Thirty years ago, they would not have been. Changing the list of which devices count means the surveys from different years are not comparable because they measure different lists.

When you pretend what's being measured is "(consumer) electronic devices", then it would make sense to compare studies from different years, because they appear to measure the same thing. But really one survey is about list A and another survey from another year is about list B, and calling the two lists by the same name doesn't make them the same thing. Epstein's comparison between the present and thirty years ago, using two different surveys of two different things, is a mistake.

I informed Epstein of these scholarship errors and he did not fix them. He should not repeat unsourced claims from Youtube that are presumably based on misusing the readily available invalid research. The truth matters.

Elliot Temple

| Permalink

| Messages (0)

Applying Philosophy to Politics

In part 1, we took a look at some "He said, she said" reporting. (Read that first.) It was poor reporting because it didn't do any research into which claims are true, nor did it suggest the reader investigate. It left people to simply listen to the claims of whoever fits their political affiliation. It's not a rational approach to listen to and believe the unargued, uninvestigated claims of Democrats if you're a Democrat, or of Republicans if you're a Republican. But Fox News didn't aim for anything better.

Correctly understanding a political issue like power plant emissions regulations requires philosophical background knowledge. Most political pundits do not have this knowledge and therefore do their jobs incompetently.

A good example of philosophical background knowledge is an understanding of the role of government in society. Without a concept of what the purpose of government regulations is, and when and why they should (and shouldn't) be created, the issue cannot be rationally evaluated.

This raises a tricky issue. Everyone has philosophical ideas. They are not avoidable. Political commentators do have ideas about the proper role of government. The problem is they don't treat their ideas about the proper role of government as a major issue to talk about. So the topic doesn't get an appropriate critical examination. Unexamined (and sometimes even unstated) philosophical ideas are no substitute for ones which are stated clearly, critically considered, and integrated into one's explanations.

I know where my philosophical ideas come from. I know which authors I'm agreeing with, and why. I know the history of ideas I've accepted. I know what the competing philosophical claims are, who advocated them, their history, and why I disagree. This is what it means to take a serious philosophical approach, as opposed to just having some philosophy you picked up somewhere and don't think about much. Everyone should do this, especially people involved in intellectual pursuits like politics. Most people do not do this. (I don't know every detail of everything. But I know a lot about this stuff, especially for issues I write about.)

The proper role of government in society is to protect its citizens from force. That is my philosophical position. Arguing for it in full would take a long time, and I don't want to go into that right now. I want to illustrate how to use this philosophical position to sort through political claims. Fortunately, arguments on this topic have already been written down. If you're interested, you can read The Virtue of Selfishness by Ayn Rand, especially "The Nature of Government". Atlas Shrugged also helps explain. If you read those two books and still have any questions or arguments, contact me and I'll be happy to talk about the issue more.

Now let's look at some of those political claims:

However, this issue is easy to evaluate using an understanding of the role of government. The key issue here is not whether it will create or destroy jobs. The key issue is not whether it will cut bills or cost billions. A more fundamental issue is whether the government is acting according to its proper role.

Creating jobs is not the role of the government. The free market should take care of that. The government is like a giant bureaucratic company with 20 levels of management, except way bigger and with less accountability. The government is huge, heavy-handed and clumsy. I don't mean that as an attack on the government, merely facts (for details, see the books mentioned earlier). That is OK. The government doesn't have to be agile and efficient. It has a particularly hard job to do; as long as it does that job decently then that's good enough. It should not try to do everything well, it should stick to its purpose.

Given this perspective, we can ignore a lot of claims being made. Given that its government action designed to hinder companies from making the choices they think are economically best, I would expect it to do economic damage (that's another philosophical issue, though I've just mentioned it briefly and don't have space to explain today). However, that isn't the point. The government should not be in the business of creating or destroying jobs, raising or lowering bills, or otherwise trying to control the economy. The government should stick to protecting people against force.

The only defense of a regulation is that it protects people against force. The Obama administration does mention this by saying, "save thousands of lives". Saving lives is a legitimate purpose of government. The political commentary should focus on whether the regulation will or will not protect people. (This is complicated because doing economic harm does cost lives in the big picture, e.g. by leaving less wealth left over that can be used for medical research. As emotionally awkward as it may be, saving specific lives in the short term does not have unlimited value.)

So, key issue: Will burning less coal in power plants save lives? Will it protect people? No. (And neither side of the political debate is focusing on arguing this key issue.)

Coal power plants provide electricity which saves lives. Coal-based electricity helps people better control their lives and environment (for example, air conditioning saves lives during heat waves), and do less back-breaking manual labor. It dramatically improves quality of life. Reducing access to electricity does not protect people, it hurts people, so the government shouldn't do it. In part 3, I elaborate more on this view of electricity, and the related philosophy.

Correctly understanding a political issue like power plant emissions regulations requires philosophical background knowledge. Most political pundits do not have this knowledge and therefore do their jobs incompetently.

A good example of philosophical background knowledge is an understanding of the role of government in society. Without a concept of what the purpose of government regulations is, and when and why they should (and shouldn't) be created, the issue cannot be rationally evaluated.

This raises a tricky issue. Everyone has philosophical ideas. They are not avoidable. Political commentators do have ideas about the proper role of government. The problem is they don't treat their ideas about the proper role of government as a major issue to talk about. So the topic doesn't get an appropriate critical examination. Unexamined (and sometimes even unstated) philosophical ideas are no substitute for ones which are stated clearly, critically considered, and integrated into one's explanations.

I know where my philosophical ideas come from. I know which authors I'm agreeing with, and why. I know the history of ideas I've accepted. I know what the competing philosophical claims are, who advocated them, their history, and why I disagree. This is what it means to take a serious philosophical approach, as opposed to just having some philosophy you picked up somewhere and don't think about much. Everyone should do this, especially people involved in intellectual pursuits like politics. Most people do not do this. (I don't know every detail of everything. But I know a lot about this stuff, especially for issues I write about.)

The proper role of government in society is to protect its citizens from force. That is my philosophical position. Arguing for it in full would take a long time, and I don't want to go into that right now. I want to illustrate how to use this philosophical position to sort through political claims. Fortunately, arguments on this topic have already been written down. If you're interested, you can read The Virtue of Selfishness by Ayn Rand, especially "The Nature of Government". Atlas Shrugged also helps explain. If you read those two books and still have any questions or arguments, contact me and I'll be happy to talk about the issue more.

Now let's look at some of those political claims:

The Obama administration claimed the changes would produce jobs, cut electricity bills and save thousands of lives thanks to cleaner air.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce argues that the rule will kill jobs and close power plants across the country.At face value, it's hard to tell who is right. I don't know the details of these proposed power plant regulations, and I doubt you do either. Different prestigious groups are making directly contradictory claims. At least one group must be mistaken. Many people would decide which group is mistaken by political affiliation, but that method is incapable of figuring out the truth.

The group is releasing a study that finds the rule will result in the loss of 224,000 jobs every year through 2030 and impose $50 billion in annual costs.

However, this issue is easy to evaluate using an understanding of the role of government. The key issue here is not whether it will create or destroy jobs. The key issue is not whether it will cut bills or cost billions. A more fundamental issue is whether the government is acting according to its proper role.

Creating jobs is not the role of the government. The free market should take care of that. The government is like a giant bureaucratic company with 20 levels of management, except way bigger and with less accountability. The government is huge, heavy-handed and clumsy. I don't mean that as an attack on the government, merely facts (for details, see the books mentioned earlier). That is OK. The government doesn't have to be agile and efficient. It has a particularly hard job to do; as long as it does that job decently then that's good enough. It should not try to do everything well, it should stick to its purpose.

Given this perspective, we can ignore a lot of claims being made. Given that its government action designed to hinder companies from making the choices they think are economically best, I would expect it to do economic damage (that's another philosophical issue, though I've just mentioned it briefly and don't have space to explain today). However, that isn't the point. The government should not be in the business of creating or destroying jobs, raising or lowering bills, or otherwise trying to control the economy. The government should stick to protecting people against force.

The only defense of a regulation is that it protects people against force. The Obama administration does mention this by saying, "save thousands of lives". Saving lives is a legitimate purpose of government. The political commentary should focus on whether the regulation will or will not protect people. (This is complicated because doing economic harm does cost lives in the big picture, e.g. by leaving less wealth left over that can be used for medical research. As emotionally awkward as it may be, saving specific lives in the short term does not have unlimited value.)

So, key issue: Will burning less coal in power plants save lives? Will it protect people? No. (And neither side of the political debate is focusing on arguing this key issue.)

Coal power plants provide electricity which saves lives. Coal-based electricity helps people better control their lives and environment (for example, air conditioning saves lives during heat waves), and do less back-breaking manual labor. It dramatically improves quality of life. Reducing access to electricity does not protect people, it hurts people, so the government shouldn't do it. In part 3, I elaborate more on this view of electricity, and the related philosophy.

Elliot Temple

| Permalink

| Messages (0)

Attitudes to Criticism

in the social popularity game, criticism is a negative.

in the truth-seeking game, criticism is a positive.

you can get an idea of which game people are playing by their reactions to criticism.

if someone wants public praise and private criticism, they may be trying to play both games. but the games contradict, and the contradiction will destroy them.

in the truth-seeking game, criticism is a positive.

you can get an idea of which game people are playing by their reactions to criticism.

if someone wants public praise and private criticism, they may be trying to play both games. but the games contradict, and the contradiction will destroy them.

Elliot Temple

| Permalink

| Messages (17)