In 2020, I accused Dennis Hackethal of plagiarizing me (and plagiarizing David Deutsch) in his book A Window on Intelligence: The Philosophy of People, Software, and Evolution – and Its Implications (2020). I tried to resolve the matter with him by email even though he published the book without giving me any advance warning. Regarding a part I said plagiarized me, he responded: "it looks like you did tell me that [sentence], in which case the right thing to do is to credit you". He then asked me to send him many issues at once, I did, and he stopped responding without denying plagiarism or communicating any objections to my post. Until 2024, I thought he knew he was guilty and was strategically ignoring me.

In 2024, Hackethal denied plagiarizing me, but he gave no evidence or reasoning. It was just an unargued assertion. In 2025, he gave some reasoning about why he thinks he didn't plagiarize me. (Timeline.)

His 2025 reasoning focuses mainly on straw manning and misquoting my criteria for what plagiarism is, then claiming I'm a hypocrite who is also a plagiarist by those false criteria. He inaccurately summarizes what my accusations say. He doesn't focus on defending his book.

This post will discuss DARVO and Hackethal's defenses against plagiarism. I tried to comment on everything resembling a defense of his book, but he mostly attacked me instead of defending his own actions.

What Is Plagiarism?

Hackethal presents inaccurate information about what I think plagiarism is and he doesn't specify what he thinks it is. I'll clarify:

Plagiarism is taking credit for ideas or knowledge that you got from a source rather than creating yourself.

Or, as I put it in 2020 when criticizing Hackethal's book:

Plagiarism is taking credit for ideas or writing that isn’t yours.

The New Oxford American Dictionary defines plagiarism as:

the practice of taking someone else's work or ideas and passing them off as one's own

The Macmillan English Dictionary defines plagiarism as:

the process of taking another person’s work, ideas, or words, and using them as if they were your own.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines plagiarize as:

to take and use as one's own the thoughts, writings, or inventions of another.

These all say pretty much the same thing. I think it's important to understand that any type of knowledge can be plagiarized, even if it's not in words or doesn't resemble a scientific theory.

DARVO

Yellow blockquotes are from Hackethal and omit links. Italics are in the originals but bold is added.

If I seem nitpicky as you read on, keep in mind that I’m not applying my own standard but his [Temple's] – I don’t consider the examples I give actual plagiarism, and neither should you. I merely want to prove his hypocrisy.

Hackethal's approach is called DARVO: Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender. First he denied plagiarizing me. Then, instead of analyzing his book and trying to defend it, he attacked me. He tried to shift the narrative to reverse who is the victim and who is the offender.

Hackethal's response to evidence of his wrongdoing is to go on offense. Instead of defending his book passages, he says that some of my blog and forum posts don't name David Deutsch while discussing his ideas. But those informal posts don't take credit for Deutsch's ideas. Deutsch was mentoring me while I wrote many of them and, to the best of my knowledge, he thought they were fine (we discussed my posts hundreds of times, he didn't raise concerns, and he often expressed praise, approval and encouragement). Leaving out a citation in an informal context is different than taking credit for inventing an idea. If a reader doesn't know where you got an idea, but doesn't think you invented it, that isn't plagiarism. And I did credit Deutsch hundreds of times.

I don’t consider the examples I give [of Elliot Temple's writing] actual plagiarism, and neither should you.

Hackethal later called me a plagiarist on Twitter with no evidence, reasoning, details or link. If he doesn't think these examples are actual plagiarism, then why is he calling me a plagiarist? When you call someone a plagiarist you should give examples and reasoning. This seems like more DARVO: he's calling me a plagiarist, with zero evidence, because I called him one (with evidence).

Permission to Plagiarize?

One of Hackethal's defenses is that, in one case, I allegedly gave him permission to use some of my ideas without crediting me:

‘Maybe Deutsch gave Temple permission to use those ideas.’ Maybe, but I had Temple’s permission to use examples of his to explain a concept in my writing, yet he claimed I plagiarized it.[3] He conveniently doesn’t mention that in his article.[4] That’s dishonest – see my discussion of honesty below. The fact that I asked for permission shows that I’m considerate, but if he mentions that, people might not believe his plagiarism narrative about me.

I don't know what the first sentence is a quotation of, if anything.

Hackethal's footnote 4 admits that I publicly mentioned the permission in a video. He knows I wasn't trying to hide it.

Hackethal's footnote 3 says:

After helpfully suggesting an improvement to one of Temple’s blog posts, I asked him on 2019-01-30 whether I could use my own translation of his programming examples into another language in my writing. I asked: “With your permission, I’d like to use these examples […] in my paper.” He replied that same day: “Sure.” Temple does not credit me for the improvement, by the way. More hypocrisy. ↩

These quotes are accurate but they don't say what Hackethal seems to think they say. He didn't ask for, nor receive, permission to use my examples without credit. He also didn't ask for, nor receive, permission to use them in a book. If you want someone to be your ghostwriter, you have to ask for that explicitly, and probably pay them. A reasonable person would interpret his question as asking for permission to quote or paraphrase me with credit.

There are cases where asking for permission is unnecessary but people still do it. Asking can be a courtesy. And written permission is a better defense against copyright complaints than fair use.

I thought Hackethal was asking for those two normal reasons (courtesy and greater security against copyright complaints). It didn't even occur to me that he was asking for permission to put the material in his paper with no citation or credit. That would be unusual and it would be unethical even with my permission.

Even if someone gives you permission to use their work without crediting them, e.g. you hire someone to write your essay for school, that is still plagiarism. Permission and fair use are both defenses against copyright infringement but they aren't defenses against plagiarism.

Hackethal doesn't seem to understand plagiarism, or know what is or isn't plagiarism. That makes his denials of plagiarism pretty worthless. It sounds like he would intentionally use ideas without crediting his source – plagiarize – if he thought he had permission. And he apparently thought he had permission from me.

Also, the reason I didn't credit Hackethal for the improvement he suggested is because it wasn't an important, original idea. He suggested changing one tiny detail in order to prevent a potential pedantic complaint. I generally don't credit people for correcting my typos or making small wording suggestions. This is standard practice followed by other authors. For example, I made nine suggestions for Jordan Peterson's book, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos. Peterson thanked me by email and said the book would be changed "asap", but he didn't publicly credit me. That's fine because my contributions were small.

Plagiarism Checkers

I also ran my book through an online plagiarism checker before publication, which came up empty – more evidence that I’m considerate

This is a bad argument. Those checkers are well known to provide lots of false negatives and false positives.

Even if he had done his best to check for plagiarism before publication, his actions after becoming aware of the problem are more important. He didn't say "Sorry, the online checker I used missed it. I'll fix it ASAP." His completely different behavior is what prompted me to publish a blog post.

Also, since Hackethal knew he had recently learned directly from me about topics covered in his book, and he knew my name wasn't in the book, he should have reviewed my material and our interaction history to check for potential plagiarism instead of just using a generic online checker.

When he hired me to teach him or asked for free help on my forum, he didn't disclose that he was writing a book (or planning to write one soon? he still hasn't shared the timeline). He also didn't share any draft material before publication to let me comment, didn't send me a courtesy copy, and didn't even notify me when the book was published.

Cryptomnesia

Even though I avoided Temple’s blog for years to prevent cryptomnesia,

Why did Hackethal stop avoiding my blog? Why did he start reading it again then use ideas that are on my blog for Veritula? He doesn't say. He should stay away. He seems to be admitting that he made an intentional decision to read my blog in the time period leading up to creating Veritula.

Cryptomnesia is when you remember ideas but you mistakenly think they're new thoughts, not memories. This can lead to accidental plagiarism. If Hackethal accidentally plagiarized, he could have apologized and fixed his book. Instead, he refused to discuss the matter, which is why I went public and blogged about it.

Also, he hasn't admitted to any cryptomnesia or accidental plagiarism. This doesn't work as a defense if you don't claim that it happened. He continues to deny me credit on purpose, and repeatedly attacks me, instead of saying he had a memory error and fixing it.

Can Teaching, Organizing or Presenting Be Plagiarized?

I didn’t plagiarize Temple on any of these points [related to Nick Bostrom]. Someone can reasonably claim to have been plagiarized only when they came up with the ideas in question. Those aren’t Temple’s ideas. They’re Deutsch’s. Temple takes credit for Deutsch’s ideas, in an article about how one shouldn’t take credit for other people’s ideas! At first I thought maybe Temple wanted credit for telling me about those ideas (“got from”). That would be unreasonable, even if he did tell me. You don’t need to credit your high-school math teacher every time you write about calculus. (Calculus is so widely known that you wouldn’t need to credit anyone, even its originators, but that’s not the point – it’s that your math teacher didn’t come up with it. You could credit him as a courtesy for teaching you, but it’s not plagiarism if you don’t.)

Teaching methods and ways of organizing or explaining ideas can be plagiarized because they can involve important, original knowledge. In general, any type of knowledge can be plagiarized.

For example, LearnCraft Spanish has a teaching method where they start with prepositions, conjunctions and grammar. They delay teaching nouns, verbs and adjectives until later. That's unusual. Their method also involves mixing English and Spanish words in the same sentence. Although they didn't invent Spanish, someone could still plagiarize their way of teaching Spanish.

If you write a book teaching calculus, you could easily plagiarize your calculus teacher. That's different than writing a book about another topic, e.g. physics, which uses calculus and expects readers to already know it.

Hackethal's book doesn't merely use ideas I taught him; it focuses on teaching or explaining philosophy ideas, and they're often the same ideas I taught Hackethal being explained in similar ways with similar words to how I explained them to him.

Also, in general, secondary sources can be plagiarized. Suppose Emily reads a lot but doesn't come up with any innovative new ideas. She writes a book sharing 50 interesting ideas from 50 different thinkers she read. She cites every idea correctly. Now Jacob comes along and reads Emily's book. He writes a book with the same 50 ideas and copies Emily's 50 citations but doesn't cite Emily. He has plagiarized Emily because he used her ideas and creative work without crediting her. She did thoughtful work to gather and present those ideas, and Jacob copied her results without citing his source. Her selection of 50 ideas had knowledge from her creativity and research, and that knowledge can be plagiarized. Jacob is pretending to have done research that he didn't do but Emily did; he's taking credit for her accomplishments.

Hackethal seems to be admitting ("Someone can reasonably claim to have been plagiarized only when they came up with the ideas in question.") that he would leave out citations for secondary sources, intentionally, because he (incorrectly) thinks that can't be plagiarism. Hackethal's denials of plagiarism don't mean much if he doesn't understand what plagiarism is.

Academics have written about secondary source plagiarism (1, 2, 3, 4), also called bypass plagiarism (5, 6). It's plagiarism to get a quote or fact from a secondary source, then copy the primary source citation from the secondary source without citing the secondary source (unless you get a copy of the primary source, read it yourself, and use material directly from it without using anything from the secondary source). And secondary sources frequently contain new knowledge that isn't in the primary source (e.g. additional analysis), so taking credit for that knowledge without citing the secondary source is also plagiarism, even if one acquires, reads and cites the primary source.

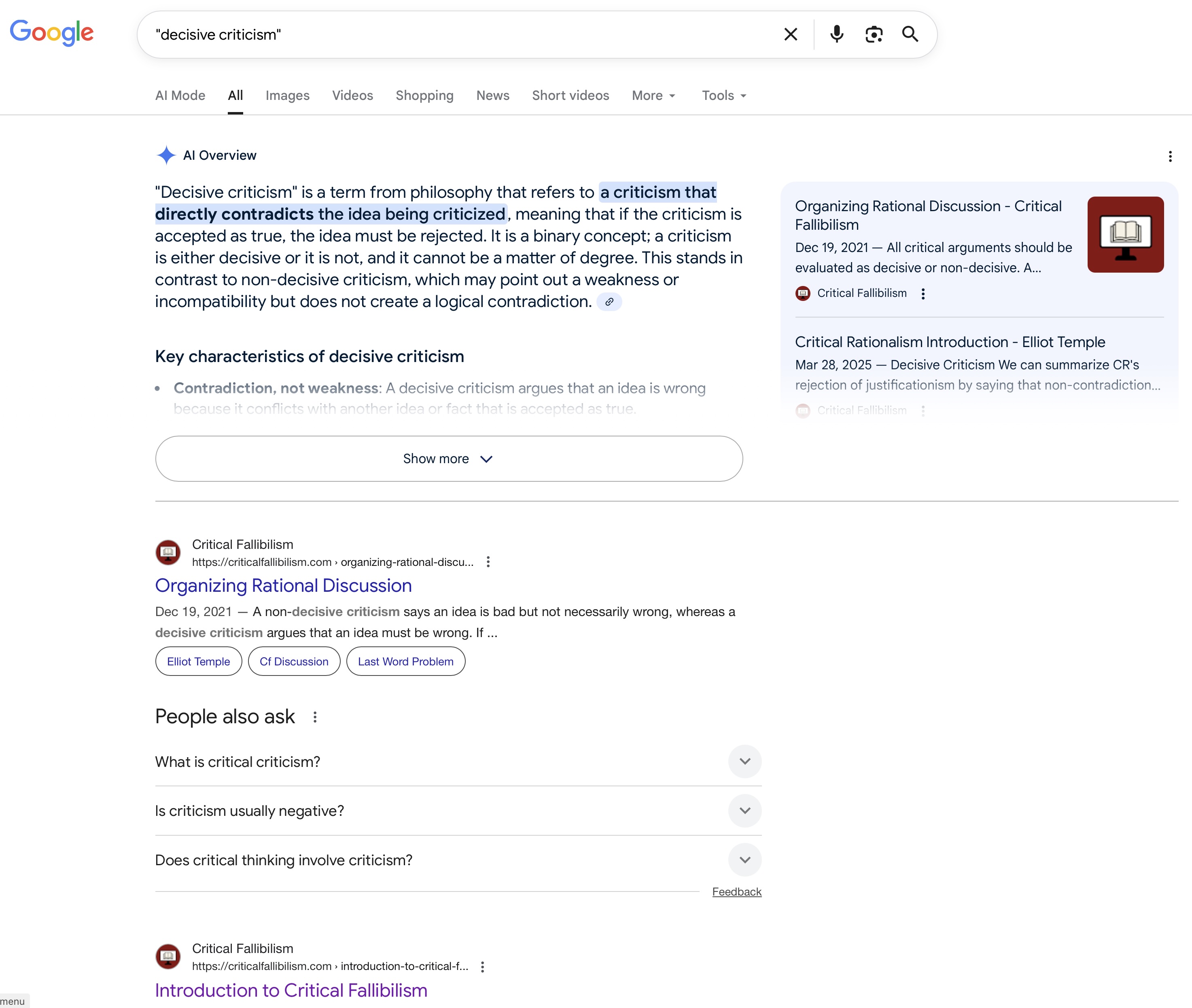

Hackethal seems to think that me not wanting to be secondary-source-plagiarized is unreasonable: "At first I thought maybe Temple wanted credit for telling me about those ideas (“got from”). That would be unreasonable, even if he did tell me." He's basically admitting that he would leave out citations to me on purpose because he thinks plagiarism only applies to some types of knowledge but not others. He thinks citing me when I am his source is an "unreasonable" request, whereas many academics would call not citing me "plagiarism". (To be clear, using me as an uncredited secondary source is only one of the concerns. He also appears to have used me as an uncredited primary source by using my original philosophical ideas about decisive arguments and binary evaluations for Veritula.)

AGI Alignment and Slavery

But then I saw that Temple claims in this video, in reference to alignment and slavery: “[T]hat’s my idea!” Then he backtracks a bit: “It’s implied by [Deutsch’s] ideas, but [he] didn’t publish it and I’m the one who told the world.” As for telling “the world”, consider that Temple’s video has 165 views almost five years later, which gives you an idea of how little of an audience he really has. Contrast that with Deutsch, who had, in fact, published the idea to around 21,000 followers in 2019, ie before I published my book. He also published it on Sam Harris’s podcast back in 2015, where I heard it years before I even knew Temple. And I know from personal conversations with Deutsch that he had that idea long before he appeared on Harris’s podcast. [no links omitted]

Hackethal says he got an idea (that he didn't cite a source for) from Deutsch, not me. He's debating who he plagiarized, not whether he plagiarized. His claim is that he never plagiarized anyone, so this defense is illogical.

While I did credit Deutsch in my unscripted video, I was skeptical then, and remain skeptical now, that Hackethal got this from Deutsch.

The issue isn't when Deutsch had the idea, but when and where he shared it, and where Hackethal got it. Hackethal often argues about irrelevant points (like when Deutsch privately thought of an idea), which may confuse readers about what the issues are.

The size of my audience is also irrelevant to whether Hackethal got the idea from me or Deutsch. Hackethal is in my audience. It doesn't matter if lots of other people didn't learn something from me if Hackethal did.

Having a small audience makes me more vulnerable to plagiarism since few people reading Hackethal's writing would be able to recognize when it plagiarizes me.

Hackethal participated in multiple discussions about these topics at my community before Deutsch published the 2019 tweet that Hackethal linked. As to the 2015 podcast, Hackethal couldn't have learned it then because Deutsch didn't say it there. Hackethal is (yet again) making false statements about his own sources.

In the podcast, Deutsch said that "shackling the AIs [AGIs] so that they won’t be able to get away from us and have different ideas" could lead to a "slave revolt". That doesn't explain the issue enough for someone to learn it. And it doesn't directly say AGIs are slaves, just ambiguously implies it for one extreme scenario (total suppression of different ideas and autonomy). Deutsch didn't say or imply that friendly AGI efforts in general are attempts at enslavement (they typically aim to prohibit some dangerous ideas, not prohibit all different ideas – the AGI being really smart and coming up with new and different scientific theories is actually part of the goal).

Deutsch's 2019 tweet, after Hackethal learned about these topics from me, says "Trying to shackle an AGI's thinking is slavery." That's ambiguous (what constitutes a shackle?) and isn't explained enough for anyone to learn much about this complex, difficult, unintuitive topic. Deutsch acknowledges that and his tweet also says he explained the issue in his essay in the book Possible Minds, but I checked and he didn't explain it there. By the way, I actually discussed Possible Minds with Hackethal, who was a beginner who needed a lot of help to try to understand material from that book.

Hackethal claims to have learned about AGI alignment and slavery from Deutsch's 2015 podcast appearance. I already discussed that Deutsch didn't share the idea then. But also, in a 2019 post at my forum titled "Friendly AI [AGI]", Hackethal began "Elliot and I talked about this and decided it would be interesting to start a thread about it and see what other people think." There is written documentation about how and where Hackethal learned this stuff.

In our conversation, Hackethal made it clear he hadn't learned it in 2015 or at any time prior to 2019 because he disagreed with it (or didn't understand the topic enough to know what his claims meant): "As I currently understand it, the AI [AGI] is an explainer, but has no capacity for emotions." In a response I said "I think [the AGI would] have preferences – it wouldn't want to do some things. And it'd want to be paid for work it does, not work for free. It'd be a person." Hackethal replied making it clear to me that he didn't understand enslaving an AGI was possible: "Again, you speak in terms of preferences and wants, which are all emotions." He didn't think an AGI could want or not want to do some actions, or could want to be paid for its work. He didn't see AGIs as being full people that are the same as human beings (I also brought up to him that AGIs could have teachers just like human children do). You can't enslave something that doesn't prefer anything over anything else – that's like "enslaving" a rock, grass, or an NPC in a present-day video game like World of Warcraft.

Unlike me, Deutsch, Hackethal's book or Hackethal's current view, Hackethal in 2019 thought animals had features that AGIs wouldn't: "Many animals have preferences". I responded with links to some of my material that disagreed with him about animals. He used some of that material, which I shared in that email, in his book. Other people also responded arguing with him. It looks like we changed his mind, particularly me (I made many essays and videos about this, which influenced the other posters too).

A year after these conversations, Hackethal published a book where he now agreed with and explained theories he'd argued against and/or been ignorant of when he joined my community. Unlike Deutsch, I covered the topics extensively in public. Hackethal claims citing me would be unnecessary even if he did learn these things from me because I learned some of these ideas in private conversations with Deutsch. Even if that were correct, Hackethal should still cite the source he got ideas from, even if it's a secondary source, and he could also cite Deutsch or share speculations about Deutsch. Hackethal doesn't actually know what was said in my private conversations with Deutsch: he doesn't know what I learned from Deutsch, what Deutsch learned from me, and what Deutsch and I disagree about. Instead of basing citation decisions on speculations about other people's private conversations, you're supposed to cite the sources that you actually used (and optionally add additional notes, comments or cites if you think they're relevant). It sounds like Hackethal knows he learned these ideas from me and he's making bad excuses for intentionally not citing me.

Since none of the sources Hackethal brought up regarding AGI alignment actually teach the idea, they seem to be excuses made up after the fact, not where he really learned it, which I still think was from me. But even if Hackethal somehow learned it from Deutsch (or someone else he didn't cite), that would still be plagiarism, since he gave these Deutsch sources in his February 2025 blog post, not his March 2020 book.

Smears

I have more examples of Temple’s use of others’ ideas without credit, but I think I’ve given enough. There are pages upon pages filled with what Temple would consider actual plagiarism, on his own blog and some of his other websites.

Plagiarism involves taking credit for inventing ideas, not just using them without credit. Hackethal doesn't seem to understand the difference. Suppose I write "If you find any errors in my essay, please send me corrections." Then I'm using fallibilism, an idea which I learned about from Karl Popper and David Deutsch, but it's OK not to cite them when I write that sentence. Although my sentence doesn't credit them, it wouldn't be plagiarism because it doesn't take credit for inventing fallibilism.

Overall, Hackethal wrote a lot about plagiarism but barely any of it even tried to defend his book. He made many false claims about my opinions. He put words in my mouth in order to attack me. He had the opportunity to discuss with me what I consider plagiarism and why but he declined. He could have learned about plagiarism by Googling it or he could have done a better job reading what I said about it. Instead, he's smearing me by lying about what I think. This is a way to attack me and avoid saying what he thinks plagiarism is or how he evaluates what is or isn't plagiarism.

Instead of analyzing his book using a standard of plagiarism he believes is correct, he analyzed my blog using a standard of plagiarism he believes is incorrect. This falsely implied that my criticisms of his book used the incorrect standard that he misattributed to me.

He also wrote tens of thousands of words about me on other topics besides plagiarism. The pattern there is also DARVO: he mostly attacks me instead of trying to defend his own actions.

Also, Hackethal's many examples of my writing that "Temple would consider actual plagiarism" are absurd. I'll briefly discuss two:

I discussed ideas from the book The Beginning of Infinity in a post to the The Beginning of Infinity forum (reposted to my blog with attribution). The credit is in the forum name. Hackethal says I would consider that plagiarism, but I wouldn't.

Another of Hackethal's examples is that I used Ayn Rand's concept of an "active mind" in a post which names Rand approximately 21 times, quotes four passages where she talked about "active mind", and cites those quotes to "Ayn Rand's Philosophical Detection, from Philosophy: Who Needs It". Hackethal falsely claims that I would consider that plagiarism. I'm not joking. His examples are that bad. (Thank you Jarrod for pointing this out.)

Copyright

I said Hackethal's book violated my copyright. It was only a small amount of text, but it did violate my rights and provide two particularly clear examples of plagiarism (because he used my words instead of just my ideas). It wasn't a major copyright concern (if he had credited me, then I would have considered it fair use), but he keeps falsely telling people that I'm unreasonably picky and aggressive about copyright.

What was his defense of his book? He said the copyright complaint only applied to a small amount of his book and he attacked me at length. Instead of giving a view of copyright which he thinks is correct and evaluating his book using that view, he instead evaluated my writing using a view of copyright which he thinks is incorrect. He falsely attributed the incorrect view of copyright to me and called me a hypocrite.

Context

Hackethal wrote a book which says it offers a "bold new explanation" and "unparalleled insight". In this context, readers will reasonably assume ideas the book explains (which aren't common knowledge) were invented by Hackethal unless he credits someone else.

I wrote blog posts. I was open about being inspired by David Deutsch, who I talked about frequently. I wrote about Deutsch's ideas, and other ideas, for many years, without claiming to have important new ideas of my own. This is normal. Many bloggers don't have important new ideas. They're just trying to think and write about interesting topics. That can be worthwhile even without bold new explanations or unparalleled insight.

In that kind of blogging context, if an idea is mentioned without a citation, readers may not assume the blogger invented it. It depends. If explaining an idea is the main focus of a post, then the blogger should generally say where they got it, but even if they don't, readers may not assume it's original if there are no claims to originality. With Critical Fallibilism, I often clearly state when I think something is an important new idea that I developed.

I have also written forum posts, emails, Reddit comments, Tweets, Facebook messages, and so on. Do I cite everything in those informal contexts? No. If you're writing a YouTube comment, the context is so informal that people might not even believe you if you said you were sharing an important, original idea.

Not providing a source and taking credit for something are different. A book, a blog or a social media comment are different contexts. Readers judge by context what people are taking credit for. In books, especially books that claim to be sharing important, original ideas, readers tend to see any idea which is explained but not cited (and isn't common knowledge) as the author's idea.

Other context matters too, like treating different sources differently. If some thinkers gets many cites, and others don't, why is there a double standard? Having a lot of cites for some thinkers implies to readers that you're using citations, which makes the other cites being left out more misleading than it would be if there were no cites.

Another part of context is how an author would respond to questions. If someone asks me whether I invented fallibilism, I'll say that no, I learned about it from Popper and Deutsch. Although I sometimes talk about fallibilism in informal contexts without citing anyone, I don't intend to take credit for it. By contrast, Hackethal hasn't responded to my complaints by clarifying that he got a bunch of ideas from me (instead he attacked me). In addition to not putting various cites in his book, he also doesn't provide them when people ask. He seems to be intentionally claiming to have originated some ideas, which is different than merely neglecting to include some citations.

Hackethal wrote in a more formal context than me, said his book had a lot of important, original ideas (making that the default expectation for ideas the book presents without citations which aren't common knowledge), cited a lot of other ideas, and used significantly different citation policies for different sources. Then, when concerns were raised, he still refused to tell people that he learned a lot of it from me. And then Hackethal did similar behavior again, making it potentially a pattern. These contextual factors are different for Hackethal's book compared with my blog posts (and his complaints about my blog posts, like the "active mind" complaint, are ridiculous anyway).

Misquoting

When Hackethal writes about me, he makes many false statements. When I check his sources, I often find errors. You can't trust anything he presents as factual, even when he gives quotes and sources. This analysis is intended as an example to illustrate how none of his passages or claims are trustworthy.

When criticizing others, including me, Temple’s stance on plagiarism is: “Plagiarism is taking credit for ideas or writing that isn’t yours.” He says the name of the originator of an idea should be “in the main text” and “not just in the [end]note […].” He explains his stance further: “The appropriate action is to credit [the originator] by name in the main text every time one of [their] major ideas is introduced, at minimum.” He does not define “major”. “[I]ntentional malice is clear” to him when an originator is not credited “even once”. [no links omitted]

The first quote is correct. But the rest are taken out of context and presented misleadingly. He chops up my writing. Some of his paraphrases are wrong. He quotes from four separate sections of my essay but presents it as my stance on plagiarism, as if all the other quotes are my elaboration on the first quote, but they aren't. He presents me as making generic claims about principles when most of what he quotes is actually commentary on specific cases.

He [Temple] explains his stance [on plagiarism in general] further: “The appropriate action is to credit [the originator] by name in the main text every time one of [their] major ideas is introduced, at minimum.”

These quotes are from a different section. They aren't elaboration of my stance on plagiarism. I wrote about one book's treatment of one thinker, not any originator:

Besides the list of plagiarized DD [David Deutsch] topics above, all the other DD topics in the book are also plagiarized, since they aren’t some of the few topics where credit was given.

The appropriate action is to credit DD by name in the main text every time one of DD’s major ideas is introduced, at minimum.

Hackethal misquoted me by changing my comment about how a specific book should have treated Deutsch to a universal claim about how all writing should treat all originators of ideas. When I comment on specific cases, I take into account evidence and context, and I wouldn't necessarily reach the same conclusion about a different case.

Another way of looking at it is that Hackethal is presenting of my arguments as my complete, exhaustive reasoning, when they aren't and I never said they were. He even does that when I indicate incompleteness using clear words like "for example", as we'll get to soon.

He [Temple] says [as part of his general stance on plagiarism] the name of the originator of an idea should be “in the main text” and “not just in the [end]note […].”

These quotes come from a different essay section and aren't an elaboration on the definition of plagiarism that Hackethal put them after.

Hans Hass gets his name in the main text of the book too, not just in the note, as is appropriate. But ET’s [Elliot Temple's] name isn’t in the book once.

I commented on a specific passage involving Hans Hass. I didn't present a general rule that applies to all writing, as Hackethal misled his readers to believe. That's why I put it in a different section, not the section where I stated my general stance on plagiarism.

“[I]ntentional malice is clear” to him when an originator is not credited “even once”.

Hackethal misquotes me as saying you can always conclude malice when one specific piece of evidence (zero credit) is present. What I actually wrote was:

DH’s intentional malice is clear because, for example, ET’s name literally isn’t in the book even once, even though it’s packed with ET’s ideas. Details for all of these points are covered below.

I said a particular individual's malice was clear due to multiple pieces of evidence. I said "for example" and gave two pieces of evidence (name not present even once and many ideas from the same person present). I said I'd give more details later because this is from yet another section of my essay, the introduction.

Hackethal left out the "for example", my second piece of evidence, and that more details were given later. My second piece of evidence was also grammatically and logically linked to the first, not independent, which makes leaving it out even worse. He misquoted me by inserting an inaccurate paraphrase between two partial sentence quotes and leaving out key information from the same sentence.

To summarize, Hackethal quoted from four sections of my essay and falsely presents them as coming from one section with all the later quotes elaborating on the first one. He misquoted me as making generic claims when I talked about specific individuals and passages. His selective quoting and inaccurate paraphrasing hides what I actually said by leaving out names of specific individuals, changing specific claims to universal claims, and omitting key words like "for example".

Interestingly, these types of misquotes would be evaluated as correct quotations by Hackethal's Quote Checker tool. His approach to evaluating quotes pedantically focuses on changes to letters or whitespace, but it misses changes of meaning. He doesn't check whether quotes are introduced accurately or taken out of context. He doesn't check whether paraphrases inside square brackets or in quotation-adjacent text are accurate. Those things can't be checked mechanically; it takes creativity to evaluate them well. Hackethal focuses on issues that can be checked mechanically with simple software, but misquoting meanings is more important than misquoting wordings. Hackethal is also pedantic enough to call valid style choices misquotes, like not putting ellipses at the start or end of some quotes where they're optional. Hackethal presents himself as caring a lot about quotation accuracy, and he usually gets wordings right, but he often gets meanings wrong.

Conclusion

Hackethal still hasn't really attempted to defend his book against my 2020 plagiarism accusations. He didn't quote and analyze his book passages and talk about where he got the ideas. He didn't put up blog posts explaining which ideas I originated. He didn't attempt to thoughtfully discuss what plagiarism is. Instead, he used a DARVO strategy and attacked me as a hypocrite using misquoted straw man claims about what I supposedly consider plagiarism.

Hackethal also still hasn't provided basic timeline information like when he started planning or writing his book. He's been unhelpful regarding my concerns.

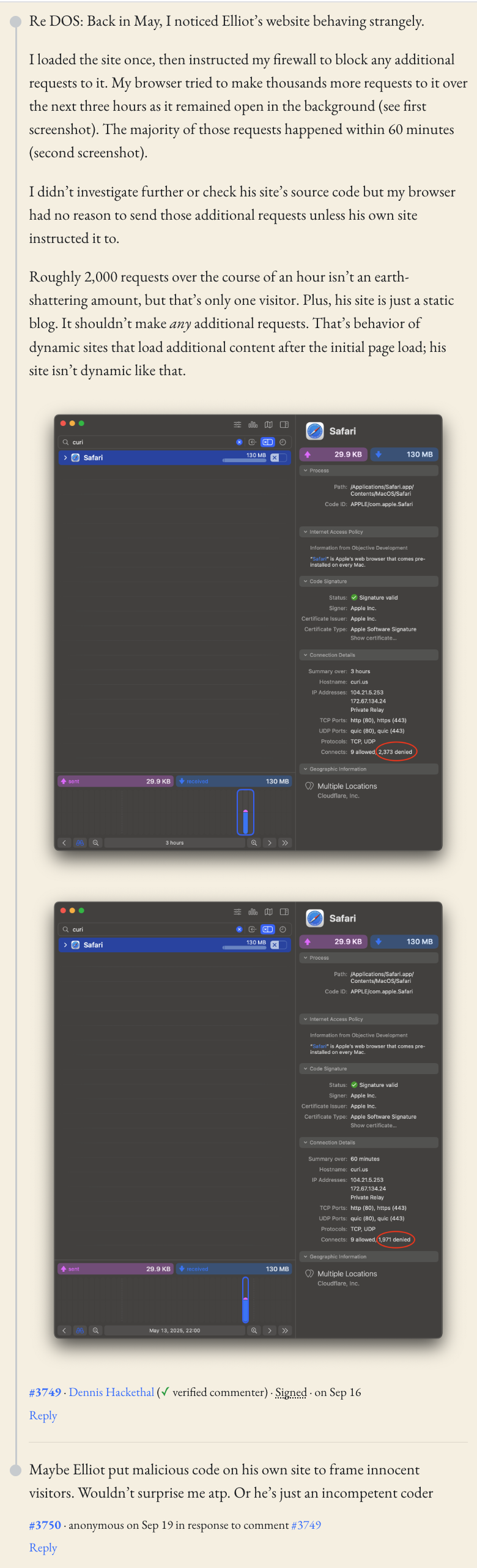

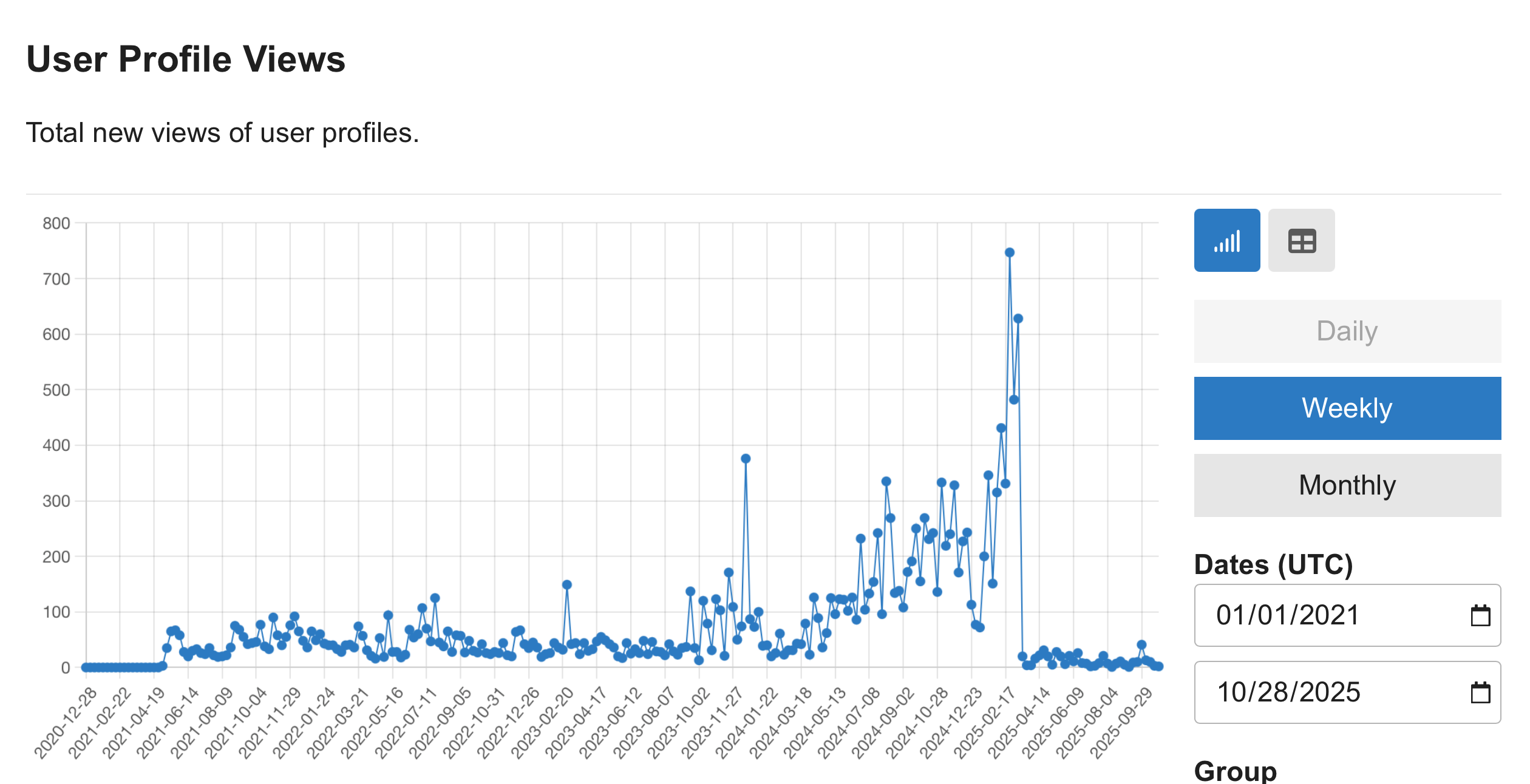

Why do I still care about this issue from years ago? Hackethal extensively attacked me in 2025, including this plagiarism DARVO. He said he won't stop, doesn't appear to have stopped, and also has been encouraging others to attack me too (including blatant defamation). He also non-consensually published photos of me which I didn't give him, which he didn't take, and which weren't available online before he published them. He's still selling the problematic book and he started using my Critical Fallibilism ideas for his Veritula website without crediting me. Also, illogically, Hackethal and some of his associates have been going around the internet falsely telling people that I'm a plagiarist (even though his own blog post claims I'm not a plagiarist, merely a hypocrite). Hackethal and his fans have recently followed me and my fans to multiple third party websites to disrupt our conversations that weren't about him.

Hackethal now has fans who think he has innovative ideas but I don't. In some cases I invented the idea and in other cases I invented a way of explaining the idea but not the idea itself (which Hackethal also didn't invent). Instead of telling people the truth, he's gone to great lengths trying to discredit me. One of his fans (who I'm not naming as a courtesy, but I'd be happy to name and credit if he requests attribution), recently told me the following:

I'd recommend creating something of significant value - like writing an extremely interesting book or blog post that gains the attention and respect from a log of reputable people (Dennis [Hackethal] and [David] Deutsch have several works like this). This is how you create a good reputation, not by emailing people telling them that someone they respect stole your idea. You seem to attempt to protect something that doesn't exist (at least in my eyes).

This person incorrectly believes that I didn't originate any significant ideas while Hackethal did. He believes that if I did good work then I'd get credit. He doesn't seem to understand that I already developed new philosophy ideas and Hackethal is writing about my original ideas without crediting me. Hackethal hired me to teach him on paid calls and now people think he, not I, originated ideas I taught him.

Also, I asked that fan "Are you willing to discuss what’s true?" at which point he responded "Please do not email me again about this." This shows the sort of hostility and irrationality that Hackethal has been working to create. No one from his side has ever been willing to attempt to have a reasonable discussion to resolve any of the conflict.

With misquotes, my primary concern is whether the meaning is accurate, not whether a tab was changed to four spaces. With plagiarism, my primary concern is that Hackethal is misleading people, not the exact number, wording and location of citations. Hackethal's dozens of false claims about pedantic details can distract from the issues that matter most.