November 1, 2019 Climate Change Discussion in the Fallible Ideas Discord Chat

Kurapika(Mentally untouchable):

What do you guys think about the tree planting event going around on youtube?

JustinCEO:

No idea what you're referring to @Kurapika(Mentally untouchable)

JustinCEO:

Can u link?

Kurapika(Mentally untouchable):

@JustinCEO https://youtu.be/U7nJBFjKqAY

Kurapika(Mentally untouchable):

This is a trend on youtube.

JustinCEO:

Watched a minute of vid, seemed bad and dumb. Will say more later

JustinCEO:

They didn't explain who MrBeast is or why we should care. Or why this was a good project. Or alternate projects they considered. Or alternate ways of implementing this project they considered. They wasted much of first minute on playing music and showing ppl doing stuff in order to create a certain kind of social vibe and pull on the puppet strings of viewers. They figure their target audience will be more likely to donate if presented with a video with the right sort of vibe instead of leading with some kind of explanations. They're right.

StEmperorAugustine:

Watched a minute of vid, seemed bad and dumb.

Probably why you should not judge a book by its cover :). The video actually has a lot of cool explanations about trees and how to plant trees using drones. I thought it was not bad and not dumb :).

curi:

It’s part of a movement to destroy civilization tho

StEmperorAugustine:

How so?

curi:

Why plant trees?

StEmperorAugustine:

A nice way to reduce co2 and increase o2 :). It is volunteering work which is great for the soul and no coercion.

curi:

Why reduce co2?

StEmperorAugustine:

Save netherlands!

curi:

The narrative you haven’t said is global warming. The goals and meaning of the movement are well known. They want to shut down the modern economy with a scare story.

StEmperorAugustine:

I feel like that's true of some but probably not true of all. However, I haven't looked at it much, not to mention the science seems rather complicated so unless you're a climate science expert what do you do?

I know a lot of it is destructive especially if they intervene in the markets etc... but volunteer tree building seems fine to me. What are the downsides of tree planting?

curi:

They are doing video propaganda not just planting trees

curi:

They are wasting millions of dollars

curi:

The way ppl like volunteer work and charity is anti capitalist

curi:

You even implied that regular work is bad for the soul and coercive

StEmperorAugustine:

ugh it is :(. I think most people hate their jobs. Though coercive? eh Idk you can always leave but many people have limited options.

curi:

Re complicated science: the tree planters didn’t care about that. Didn’t research it or try to educate ppl about it. Just risked being wrong and dragging their fans with them

StEmperorAugustine:

They trust the scientists I suppose.

curi:

Which scientists? There are scientists on both sides

curi:

Seems more like they trust NYT CNN AOC imo

StEmperorAugustine:

Seems very one sided. https://climate.nasa.gov/scientific-consensus/

StEmperorAugustine:

those are not NYT CNN and idk what AOC is.

curi:

That's corruption and the NYT, CNN and AOC are part of the cause of it. AOC is the green new deal person.

curi:

It seems one-sided in part b/c of ongoing suppression of dissent.

curi:

In part because they're dishonest.

curi:

And in part because of the broader context of what the media has said.

curi:

And by one-sided you don't really mean one-sided, you mean that one side is more popular than the other. Popularity isn't truth as any real scientist would tell you.

curi:

These are the kind of people who crusade for minorities ... but not scientific or intellectual minorities, who they try to suppress. They prefer to focus on e.g. skin color.

StEmperorAugustine:

https://skepticalscience.com/97-percent-consensus-robust.htm

curi:

That is propaganda.

StEmperorAugustine:

These are the kind of people who crusade for minorities ... but not scientific or intellectual minorities, who they try to suppress. They prefer to focus on e.g. skin color.

StEmperorAugustine:

this is true

curi:

It's propaganda which isn't even about co2 or warming. It's tangential or meta propaganda.

curi:

It's not even trying to be about science. It should be put out by pollsters not scientists.

curi:

what does NASA know about polling? not their expertise.

StEmperorAugustine:

Isn't this confating two issues though? The science of climate change and the proposed solutions. I agree that there is a lot of non-solutions and opportunism from the left using climate change as an excuse.

JustinCEO:

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.forbes.com/sites/alexepstein/2015/01/06/97-of-climate-scientists-agree-is-100-wrong/amp/

curi:

Isn't this confating two issues though?

which statement is doing that?

StEmperorAugustine:

That's corruption and the NYT, CNN and AOC are part of the cause of it. AOC is the green new deal person.

StEmperorAugustine:

how do you know that nasa and all these other organizations are the propaganda but Alex Epstein is not?

curi:

how does that comment conflate "The science of climate change and the proposed solutions. " ?

StEmperorAugustine:

Isn't the green new deal a proposed solution? if we can even call it that.

curi:

yes but what's wrong with a statement telling you who she is? you asked.

StEmperorAugustine:

I thought you issue with these people were what they were proposing and their scare mongering and stuff.

curi:

you're losing track of context

StEmperorAugustine:

but anyway, how do you know that Alex Epstein is not the propaganda?

curi:

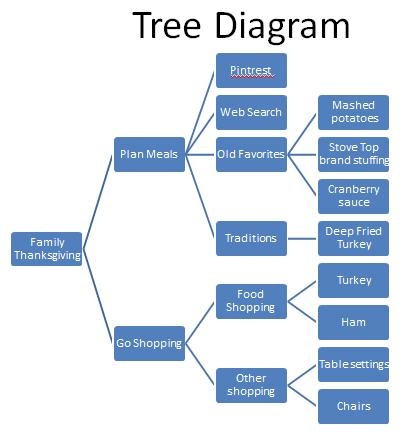

re how to tell what's right, in short you make a discussion tree and look at what arguments and questions have not been answered. https://curi.us/2229-discussion-trees-with-example

curi:

if you made a discussion tree of this discussion, it'd help you avoid losing track of the purpose and context of statements.

StEmperorAugustine:

I really rather not do that tbh. Seems like a lot of work. I am skeptical of all things related climate change. Too political. I err on the side of trusting the consensus for this one. I don't think a non-expert is in a position to understand this matter. Unless it is cases like with the green new deal or w/e its called in where a lot of the solutions have nothing to do with the climate, then you can call bs on that even as a layman.

curi:

you can't know what consensus exists, or what is a safe conclusion, without any rough approximation of the discussion tree

StEmperorAugustine:

By discussion tree you mean our discussion or you mean the climate science discussion.

curi:

climate sci discussion

StEmperorAugustine:

Yeah that honestly seems like a huge project to undertake, having a hard time seeing the upside.

curi:

if you don't want to undertake it you should, in the mean time, remain neutral

curi:

you should say you don't know and try to avoid doing things that would be evil if either side was right

curi:

that's very hard in this case b/c of the sweeping, clashing claims

StEmperorAugustine:

yea I am pretty neutral about it. Leaning on the side of scientific consensus. Which is why I trust vaccines, the earth is not flath kind of thing.

curi:

that's not neutral, it's believing propaganda. you're being a promoter of certain claims and ideas.

curi:

you are modeling the 97% consensus claim, or a similar claim, as basically true and unanswered in the discussion tree

curi:

this is a very partisan model

curi:

your sense of what's neutral is highly related to what the mainstream media says.

curi:

your positions on vaccines and flat earth are also not neutral.

StEmperorAugustine:

thats true

StEmperorAugustine:

btw is your position that there is no climate change happening? Or that it is not man made? Or that you don't beleive the predictions? or that you disagree with the solutions presented?

curi:

the prediction models are terrible. very unreliable. we don't have exact knowledge but there's presently no reason to be catastrophically worried. and the solutions are so bad they'd be bad ideas even if all the factual claims about the problem were true.

curi:

long range weather forecasts are very hard.

StEmperorAugustine:

I think you're right about the solutions. I hope you're right about the other stuff.

StEmperorAugustine:

Though if you are right, it would be terrible for public trust in our scientific institutions. So part of me hopes you're just really politically biased 😦

curi:

“You know, Dr. Stadler once said that the first word of ‘Free, scientific inquiry’ was redundant. He seems to have forgotten it. Well, I’ll just say that ’Governmental scientific inquiry’ is a contradiction in terms.”

curi:

Atlas Shrugged

curi:

our "scientific institutions" are already horribly broken and should not be trusted.

curi:

after massive intervention in the economy, the government has taken over as the primary funder of science, and the vast majority of scientific work done today is crap.

curi:

and that's part of where the global warming "consensus" comes from, btw: biased funding.

StEmperorAugustine:

That is terrible news. If you got cancer what would you even do, can't trust the scientific instiutions, doctors etc... what options are there? What a disaster 😦

curi:

our current cancer treatments are considerably better than nothing.

curi:

doctors give bad advice about many things

curi:

you should do your own research for anything important

curi:

i would research cancer a lot more if i had it

StEmperorAugustine:

how though. Can't trust the scientists that publish the research

StEmperorAugustine:

can't do your own

curi:

you can read papers

curi:

instead of trusting or not trusting the conclusions

curi:

you can figure out what the arguments about the issues are

curi:

what the data is

curi:

and think about it

StEmperorAugustine:

but you don't have any biomedical training do you?

curi:

you can discuss it and ask for criticism on FI. you can find other forums where some ppl may discuss some.

curi:

most papers can be evaluated with very little field expertise.

StEmperorAugustine:

You said most people in FI are programmers right?

StEmperorAugustine:

Oh I see

curi:

you can usually judge the quality of arguments without knowing the field, e.g. is it a correlation=causation type claim?

curi:

you can also learn some of the field.

curi:

how long does it take to get up to ~half the education they had? a month? their education was mostly wasting time.

curi:

if you're 10x or more better at learning and don't use school, you can catch up a fair amt quite fast.

curi:

maybe not half but u can be selective about which parts are relevant, leave out a bunch of stuff u don't need

curi:

like you can skimp on labwork skills if you wanna understand papers.

curi:

you may miss the occassional error about lab procedure but it's not a huge problem

curi:

i've had no trouble reading papers about neuroscience and serotonin without needing a month or even a day of study first.

StEmperorAugustine:

I think most people don't have the kind of time to do this sort of thing

curi:

you should make the time if you get cancer.

curi:

at least you should if it was just a time issue

curi:

most ppl don't have the skill for it. much bigger problem.

curi:

so, ought to learn philosophy before getting cancer.

StEmperorAugustine:

well yeah but you probably need to work as much as possible just to pay for that cancer treatment

curi:

ummm health insurance

StEmperorAugustine:

thats true

curi:

also if ur breadwinner ur spouse can look into it instead of you.

StEmperorAugustine:

I think the average person really has less choice, they kind of have to trust the experts

curi:

who gets to be labelled an "expert" and why?

curi:

that method sorta half-works for some things but is very bad for others like lots of political issues like whether minimum wage increases are a good idea.

JustinCEO:

http://justinmallone.com/2016/02/paul-krugman-is-terrible/

curi:

global warming is a political issue.

curi:

chemotherapy isn't

StEmperorAugustine:

many years of study and scientific literacy for one. Doctor goes through what, 4 years of Uni, 4-5 med, 7 of specialization. What does a waiter in East Florida do if they get cancer. Trust that Doctor seems like her option.

curi:

however i've researched some medical issues like birth control options and acutane side effects. expert doctor advice on those matters is very bad. they massively downplay risks, dangers and side effects, and play up effectiveness.

curi:

uni credentials are biased and corrupt. they aren't especially biased about cancer treatments but they are about politics. teachers and adminstrators push out students with certain ideas, punish them, falsify grades, deny funding, don't hire them, etc.

curi:

they encourage campus speakers with some ideas while suppressing others

curi:

and they will do this against majority viewpoints.

curi:

many of the positions getting this kind of biased use of power in their favor were minority positions when it started but are majority now due to decades of indoctrination from trusted authority figures.

curi:

in a free market system, which we don't have, if you got cancer you'd speak with several doctors before selecting one. just like you go talk to several lawyers about your case.

curi:

doctors vary quite a bit and blind trust in the first one you run into is unwise.

curi:

you claim doctors have scientific literacy. it appears that even medical researchers (only a fraction of them) create a majority of studies that don't replicate.

StEmperorAugustine:

THERE's NO HOPE 😦

curi:

there's lots of hope but it doesn't come from trust

curi:

gotta use your own mind, learn stuff, etc.

curi:

when you can't get to everything, you can form opinions about who has researched something with good methods already or what areas of our culture are less broken and more reliable.

curi:

for example i read Ending Aging by Aubrey de Grey and judged the argument and explanation quality in the book was good

curi:

so i have a positive opinion about his medical work and research in general, based not on trust but my critical judgment of his reasoning.

curi:

it's not that he has credentials but that i saw him do good thinking

StEmperorAugustine:

I see.

curi:

i'm sure some cancer doctors have good books or articles which are readable by advanced lay ppl, which could impress you, and which (if you had free choice of doctor) would be a much better way to choose a cancer treatment plan (consult that guy) than trusting a random doctor.

StEmperorAugustine:

What about like, before you cross a bridge. Do you trust the engineers that built it or do you have prior critical judgement of bridge builders in your area.

curi:

you, having read some of my articles, could expect me to be right about AdG without even reading his book, and you'd still have some judgment involved.

curi:

our bridge engineering standards aren't corrupt in ways that make our bridges collapse. that part of our culture isn't toooo bad. if anything i imagine they over-engineer. if a bridge was gonna collapse it'd prolly be b/c some shitty city govt hired dishonest contractors to actually build it.

curi:

btw i spoke with AdG about a paper he wrote as part of a debate with some guy about some scientific issue.

curi:

i agreed with him. he had good arguments

curi:

he believed that i was trusting his authority and reputation. he couldn't understand that i could actually evaluate the arguments in the debate myself, personally

curi:

he was unaware that they were actually 80% philosophy and more of what he wrote was in my field than his.

curi:

that kind of thing is common.

curi:

even if it was medical stuff, it's unreasonable for him to think i couldn't possibly have understood it. but it mostly wasn't and he didn't even know.

curi:

philosophy has logical priority for evaluating arguments in general. if the structure is "X implies Y, therefore I conclude Z" it doesn't matter what medical terms are contained in X, Y and Z.

curi:

scientists in all fields are inadequately trained in logic, philosophy, etc., so i can find errors like that throughout their papers.

curi:

they are always straying into my field, which they suck at.

curi:

to be fair, philosophers are, on avg, probably worse than physicists or mathematicians at such things.

StEmperorAugustine:

Interesting.

curi:

philosophy classes and professors are really fucking bad.

curi:

philosophy is the most important and most broken field.

curi:

so basically everyone in every science just wings it, improvises, dabbles in philosophy

curi:

they also trust some philosophy "experts" on some things like induction

curi:

but they also just make a bunch of philosophy claims of their own without thinking they should consult a philosopher for advice first, as they would consult a chemist if they made chemistry claims.

curi:

the situation is so broken ppl frequently don't recognize when they make philosophy claims (as they would recognize chemistry claims)

curi:

so, in short, i'm more qualified to read a paper on global warming than the author is

curi:

i'm missing less crucial expertise.

StEmperorAugustine:

Do you have any example of this?

curi:

i forget if i have one for global warming but there are several on my blog, in email archives. i analyze some serotonin stuff on YT.

curi:

i have a post on a grossly incompetent sam harris brain science paper

curi:

i've written about twin studies

StEmperorAugustine:

When I start reading a research paper. I just give up most of the time, they are written in such boring format and all the cite and numbers and math and graphs. Might as well be written in Chinese to me.

JustinCEO:

curi has read some on YT

JustinCEO:

U could watch and learn better approach

JustinCEO:

🙂

curi:

there's a generic skill of dealing with them which mostly works across fields. they aren't thatttt bad once u learn how to deal with them.

StEmperorAugustine:

awesome

curi:

Nevertheless, the existence of the expert consensus on human-caused global warming is a reality, as is clear from an examination of the full body of evidence. For example, Naomi Oreskes found no rejections of the consensus in a survey of 928 abstracts performed in 2004. Doran & Zimmerman (2009) found a 97% consensus among scientists actively publishing climate research. Anderegg et al. (2010) reviewed publicly signed declarations supporting or rejecting human-caused global warming, and again found over 97% consensus among climate experts. Cook et al. (2013) found the same 97% result through a survey of over 12,000 climate abstracts from peer-reviewed journals, as well as from over 2,000 scientist author self-ratings, among abstracts and papers taking a position on the causes of global warming.

curi:

this grossly ignores the possibility of systematic bias, suppression of speech and publication, etc., which is alleged by the other side. it's non-responsive to the counter arguments

curi:

In addition to these studies, we have the National Academies of Science from 33 different countries all endorsing the consensus.

curi:

you can see the argument quality from a statement like this. if 33 out of 33 academies endorse global warming, is that a good indicator 97% or more of more scientists agree?

curi:

as a first guess, i'd expect they endorse based on majority vote.

curi:

if 90% of scientists believe X, it'd be totally unsurprising for 100% of major, mainstream groups of scientists to have a majority that believe X.

curi:

i didn't read any other text from the page ( https://skepticalscience.com/97-percent-consensus-robust.htm ) and i already have enough info to judge they're dumb.

curi:

most ppl, when they argue, immediately make fools of themselves. doesn't take THAT much skill to see it IMO. you just think through what they say and mean and consider how it connects to their conclusion, and you look at some counter arguments and see how they handle them, and you check for bad logic and shit.

curi:

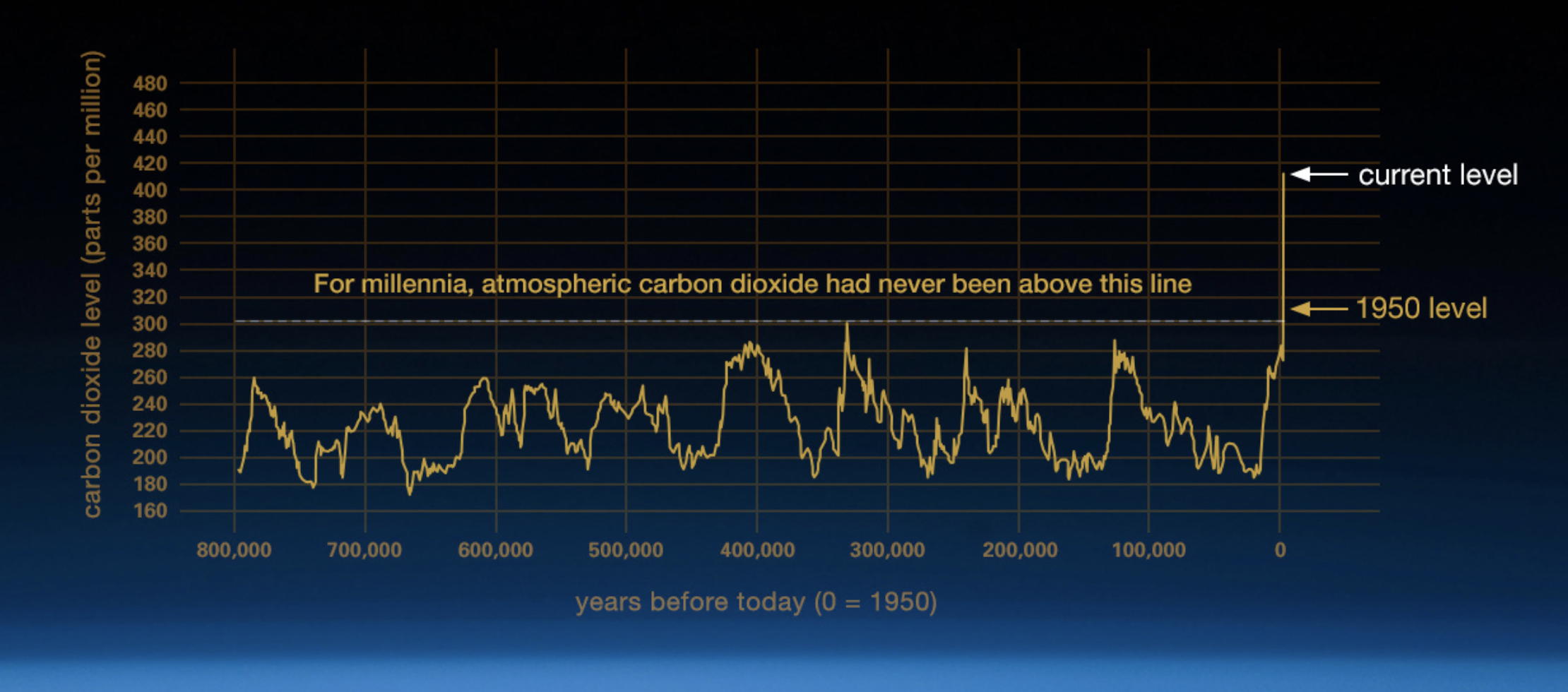

they link to this which claims earth getting warmer, blah blah

curi:

https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WG1AR5_SPM_FINAL.pdf

curi:

the general context is we're at the tail end of an ice age. so i search the paper for "iceage", "ice age", "plei", "plio" and nada. maybe i have the wrong terms. one could try harder.

curi:

no "holo", one for "medie"

curi:

• Continental-scale surface temperature reconstructions show, with high confidence, multi-decadal periods during the Medieval Climate Anomaly (year 950 to 1250) that were in some regions as warm as in the late 20th century. These regional warm periods did not occur as coherently across regions as the warming in the late 20th century (high confidence). {5.5}

curi:

no "little"

curi:

it looks to me like they are failing to address basic facts. they just ignore them

curi:

no ceno, no Quaternary

curi:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pleistocene

curi:

2.6 million years of winter ended 0.01 million years ago. irrelevant! not worth mentioning!

curi:

how much of a joke they are speaks to how biased the whole system is

curi:

tried age, era and epoch. doesn't help.

curi:

checked every use of "million". done searching.

curi:

the illusion is surface deep. besides the bad logic front and center, i click one source from https://skepticalscience.com/97-percent-consensus-robust.htm and it's got this massive problem with the first issue i check.

curi:

further, near the top

curi:

from the IPCC

curi:

The degree of certainty in key findings in this assessment is based on the author teams’ evaluations of underlying scientific understanding and is expressed as a qualitative level of confidence (from very low to very high) and, when possible, probabilistically with a quantified likelihood (from exceptionally unlikely to virtually certain). Confidence in the validity of a finding is based on the type, amount, quality, and consistency of evidence (e.g., data, mechanistic understanding, theory, models, expert judgment) and the degree of agreement1. Probabilistic estimates of quantified measures of uncertainty in a finding are based on statistical analysis of observations or model results, or both, and expert judgment2. Where appropriate, findings are also formulated as statements of fact without using uncertainty qualifiers. (See Chapter 1 and Box TS.1 for more details about the specific language the IPCC uses to communicate uncertainty).

curi:

this is epistemology. it's philosophy of science. it's my field, not theirs.

curi:

how to evaluate ideas, how to attain certainty, whether certainty comes in degrees, etc. are major epistemology topics.

curi:

my largest original contribution to the field, IMO, is basically an explanation of why their approach is irrational. https://yesornophilosophy.com

curi:

what is the role of evidence? how do you use it correctly? should you use probabilities? this is all the sort of stuff CR addresses. but they don't know anything about CR and don't care.

curi:

are they experts on Bayesian epistemology instead? no not that either.

curi:

they just plain aren't experts, by any measure, on the issues in this paragraph.

curi:

did they consult experts to help them with it? no.

curi:

re learning to read and question scientific papers, you're welcome to post them to curi or FI with questions

curi:

you will find ppl can comment on most papers, in any field, rather than just needing to leave it to the experts.

StEmperorAugustine:

Good idea.

curi:

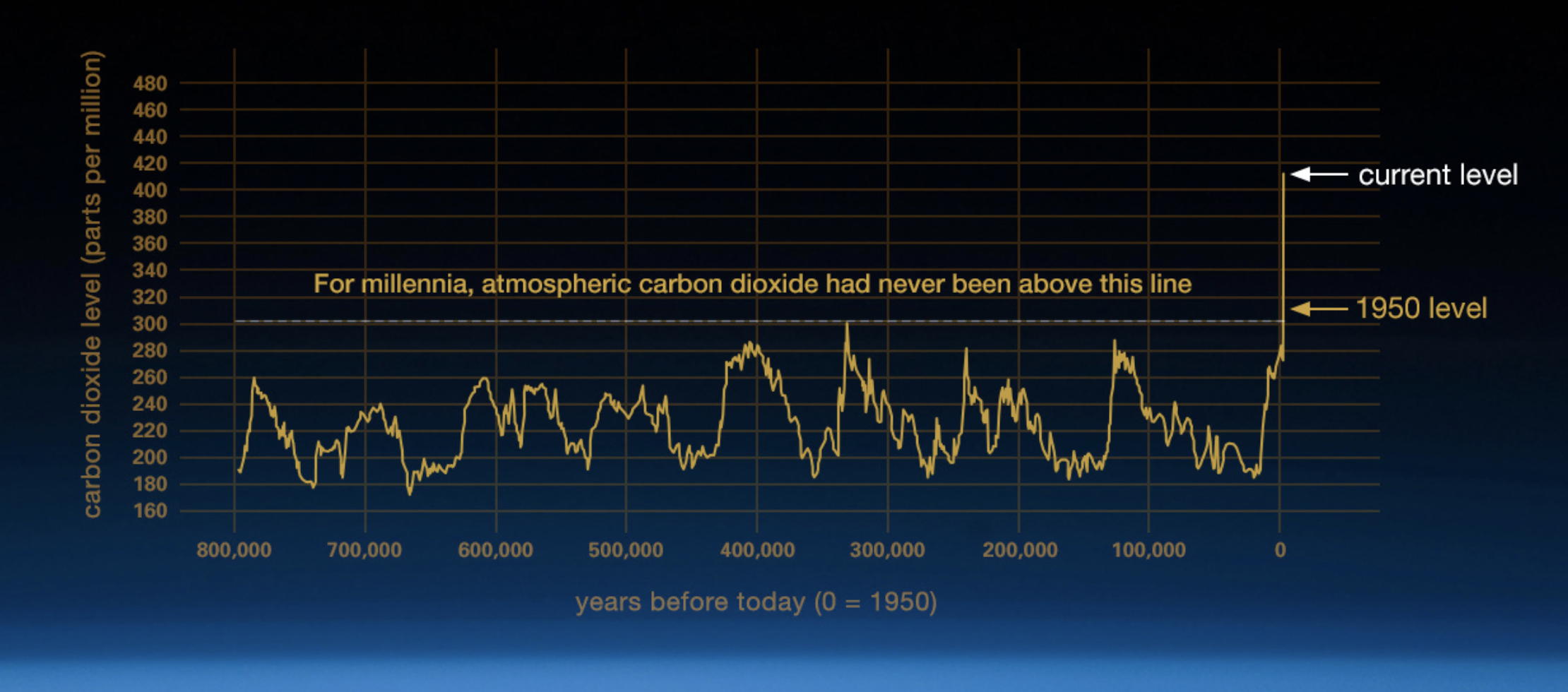

https://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/

curi:

curi:

this graph does one of the most basic ways of lying with statistics, which i read about in a middle school book report (yes, literally, not joking)

curi:

i went to the "Facts" menu, clicked "Evidence" to try to find out what is supposed to persuade me and get some scientific details, and i see this sort of propaganda instead

curi:

after that graph (anyone see the problem?) and one paragraph of text, their evidence page says:

curi:

curi:

that ain't evidence, it's appeal to authority

curi:

curi:

clicking on cite 4 does not improve things and does not lead to arguments, evidence or science for the claim that the change is driven largely by increased co2 and other human-made emissions.

curi:

this is just a propaganda website. no scientific rigor in sight.

curi:

and no need for climate science expertise to see this.

curi:

if you can find any claim which contradicts my position, and which does require climate science expertise to refute, i would be interested.

curi:

if you can't, perhaps you'll agree that says a lot about the debate.

curi:

i don't know one. i debate a lot of ppl and i've never found any pro-global-warming person who knows one.

curi:

these issues really don't take that long to deal with if u have the general purpose intellectual skills to deal with them at all

curi:

re hopeless: how easy it is to do better is very hopeful. 100 rational ppl could do so much.

StEmperorAugustine:

I am not in a position to know what claim contradicts your position so I likely would not find anything.

curi:

you're saying you're unable to find pro GW material that contradicts my claim their forecast models are unreliable junk

StEmperorAugustine:

Well I don't understand what would constitute reliable, nor understand their papers to tell the difference.

curi:

where did "reliable" come from?

curi:

o nvm

curi:

a good paper presenting a forecast model would say what standards to judge it with. it'd present standards and say how it meets them.

curi:

it'd solve your problem for you.

curi:

either self-contained or using a cite for more info.

curi:

if you can't tell – if you don't have the info to tell – that is their fault. they did it wrong.

curi:

they are supposed to present a persuasive case, not an incomplete, inconclusive case you can't judge.

StEmperorAugustine:

Do you have an example of a paper that meets that standard? could be in any field

curi:

DD's physics papers

curi:

this looks like it'd qualify http://web.gps.caltech.edu/~vijay/Papers/Chemistry/Donovan-Husain-70.pdf

StEmperorAugustine:

Anything easier to understand 😅 ?

curi:

curi:

first one i clicked

curi:

first search i did

StEmperorAugustine:

The marked difference in the chemical behavior exhibited by

the first singlet states of atomic oxygen and sulfur relative to

their ground states has been the subject of a large number of

investigations. However, data on the reactivity of the electronically excited states of other nonmetal atoms, particularly

those atoms that may lead to bond formation following reaction, are relatively limited. Historically, the work on atomic

oxygen and sulfur, principally in the ID2 state, followed extensive and detailed studies on photosensitization by metal

atoms in which the atoms, excited electronically by resonance

radiation, passed on their energy by collisions of the second

kind, thus being deactivated to the ground state or a lower

lying state.

StEmperorAugustine:

first like 3 sentences and my brain checked out already

StEmperorAugustine:

no idea what this is saying lol

curi:

the GW ppl claim, essentially, to have a bunch of papers like that on their side, and none against.

curi:

this is a lie.

curi:

their papers are much easier to read btw

curi:

if it were true, it shouldn't be that hard for you to find some such papers

curi:

they would presumably be shared and promoted

curi:

here's the first sentence of section 2 of the chemistry paper

curi:

Before proceeding with a detailed discussion of individual reactions it is convenient to summarize the general considerations necessary for a qualitative description of potential surfaces and the manner in which these influence the course of reaction.

curi:

in other words: b4 going into the details, we'll tell you how to judge read and think about the details. just the thing i said a good paper would have.

StEmperorAugustine:

oh

curi:

the paper is quite technical. it looks good tho and it doesn't appear to stray into philosophy.

curi:

so i have a positive opinion despite not knowing most of the technical stuff at all

StEmperorAugustine:

so compared to this paper, https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002

StEmperorAugustine:

where it doesn't have a bit in where it tells you how to judge and think about the details

StEmperorAugustine:

that's a bad sign

curi:

that paper is not science

curi:

they are straying into the field of pollsters

curi:

sentence 3:

curi:

A survey of authors of those papers (N = 2412 papers) also supported a 97% consensus.

curi:

the first half of the first sentence is notable

curi:

The consensus that humans are causing recent global warming is shared by 90%–100% of publishing climate scientists

curi:

they added a qualifier before "climate scientists" which you don't normally see

curi:

and there's this:

curi:

based on 11 944 abstracts of research papers, of which 4014 took a position on the cause of recent global warming.

curi:

doesn't mention the abstracts being by different ppl

curi:

anyway this issue is stupid and it's unscientific to be going around claiming popularity instead of truth

curi:

would be better to look at a paper related to climate and warming

curi:

An accurate understanding of scientific consensus, and the ability to recognize attempts to undermine it, are important for public climate literacy. Public perception of the scientific consensus has been found to be a gateway belief, affecting other climate beliefs and attitudes including policy support

curi:

god that's psychology. social science not hard science.

curi:

Consequently, it is important that scientists communicate the overwhelming expert consensus on AGW to the public

curi:

that's a political and moral conclusion, not a scientific one. it relates to values etc

curi:

From a broader perspective, it doesn't matter if the consensus number is 90% or 100%. The level of scientific agreement on AGW is overwhelmingly high because the supporting evidence is overwhelmingly strong.

curi:

that is an unargued assertion

curi:

you can't find out WHY ppl believe X by counting how many abstracts say they believe X.

curi:

as you can see, it's much easier to read this than the chemistry

curi:

they say lots of stuff you can understand without expertise about e.g. gasses

curi:

how many PUBLISHING scientists believe X is a dumb thing to count in an atmosphere where ppl denying X can get fired for it and papers denying X are often rejected or, more often, not funded in the first place.

curi:

ppl aren't even safe wearing MAGA hats

curi:

published papers with belief X says more about the beliefs of the ppl who run the journals than about the (other) scientists. (in this case, not for all journals, fields, issues). essentially they are just assuming, as an unstated premise, there's no bias here.

StEmperorAugustine:

Hmm. These are great points.

I have to go though. 😦 ttyl. Got a ton of HW to do🤢 . We are going on a trip 🤣 so I can't do it tomorrow or Sunday, and I've been procrastinating the heck of out of it.

StEmperorAugustine:

bye!

curi:

cu