Robert Spillane (RS) is a philosopher who worked with Thomas Szasz for decades. He comments on Critical Rationalism (CR) in his books. I think he liked some parts of CR, but he disagrees with CR about induction and some other major issues. Attempting to clear up some disagreements, I sent him a summary of CR I wrote (not published yet).

Previously I criticized a David Stove book he recommended, responded to him about RSI (we agree), replied positively to his article on personality tests, explained a Popper passage RS didn't understand, and wrote some comments about Popper to him.

RS replied to my CR article with 25 points. Here are my replies:

I am reluctant to comment on your article since it is written in a 'popular' style - as you say it is a summary article. Nonetheless, since you ask.......

I think writing in a popular (clear and readable) style is good. I put effort into it.

Speaking of style, I also think heavy use of quoting is important to serious discussions. It helps with responding more precisely to what people said, rather than to the gist of it. And it helps with engaging with people rather than talking past them.

(I've omitted the first point because it was a miscommunication issue where RS didn't receive my Stove reply.)

2. Your summary article is replete with tautologies which, while true, are trivial. The first paragraph is, therefore, trivial. And from trivial tautologies one can only deduce tautologies.

I’m not trying to approach philosophy by deduction (or induction or abduction), which I consider a mistaken approach.

Here's the paragraph RS refers to:

Humans are fallible. That means we’re capable of being mistaken. This possibility of making a mistake applies to everything. There’s no way to get a guarantee that one of your ideas is true (has no mistakes). There’s no guaranteed way to limit where a mistake could be (saying this part of my idea could be mistaken but not that part) or the size a mistake could be.

This makes claims which I believe most people disagree with or don’t understand, so I disagree that it’s trivial. I think it’s an important position statement to differentiate CR’s views from other views. I wish it was widely considered trivial!

I say, "There’s no way to get a guarantee that one of your ideas is true”. I don’t see how that's a tautology. Maybe RS interprets it as being a priori deducible from word definitions? Something like that? That kind of perspective is not how I (or Popper) approach philosophy.

I wrote it as a statement about how reality actually is, not how reality logically must be. I consider it contingent on the laws of physics, not necessary or tautological. I didn’t discover it by deduction, but by critical argument (and even some scientific observations were relevant). And I disagree with and deny the whole approach of a priori knowledge and the analytic/synthetic dichotomy.

3. Why are informal arguments OK? What is an example of an informal argument? It can't be an invalid one since that would not be OK philosophically, unless one is an irrationalist.

An example of an informal argument:

Socialism is a system of price controls. These cause shortages (when price ceilings are too low), waste (when price floors are too high), and inefficient production (when the controlled prices don’t match what market prices would be). Price floors cruelly keep goods out of the hands of people who want to purchase the goods to improve their lives, while denying an income to sellers. Price ceilings prevent the people who most urgently need goods from outbidding others for those goods. This creates a system of first-come-first-serve (rather than allocating goods where they will provide the most benefit), a shadow market system of friendships and favors (to obtain the privilege of buying goods), and a black market. Socialism sacrifices the total amount wealth produced (which is maximized by market prices), and what do we get in return for a reduction in total wealth? People are harmed!

Szasz’s books are full of informal arguments of a broadly similar nature to this one. He doesn’t write deductions, formal logic, and syllogisms.

Informal arguments are invalid in the sense that they don’t conform to one of the templates for a valid deduction. I don't think that makes them false.

I don’t think it’s irrationalism to think there’s value and knowledge in that price controls argument against socialism, even though it’s not a set of syllogisms and doesn't reduce to a set of syllogisms.

The concept of formal logic means arguments which are correct based on their form, regardless of some of the specifics inserted. E.g. All X are Y. Z is X. Therefore Z is Y.

The socialism argument doesn’t work that way. It depends on the specific terms chosen. If you replace them with other terms, it wouldn’t make sense anymore. E.g. if you swapped each use of "floor" and "ceiling" then the argument would be wrong. Or if you replaced "socialism" with "capitalism" then it'd be wrong because capitalism doesn't include price controls.

The socialism argument is also informal in the sense that it’s fairly imprecise. It omits many details. This could be improved by further elaborations and discussion. It could also be improved with footnotes, e.g. to George Reisman’s book, Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics, which is where I got some of the arguments I used.

Offering finite precision, and not covering every detail, is also something I consider reasonable, not irrationalist. And I’d note Szasz did it in each of his books.

Informal arguments are OK because there’s nothing wrong with them (no criticism refuting their use in general – though some are mistaken). And because informal arguments are useful and effective for human progress (e.g. science is full of them) and for solving problems and creating knowledge.

4. I wasn't aware that there was A key to philosophy of knowledge (metaphor?). And how is 'fixing' mistakes effective if we are condemned to fallibility?

It's not a metaphor, it’s a dictionary definition. E.g. OED for key (noun): "A means of understanding something unknown, mysterious, or obscure; a solution or explanation.”

What does RS mean “condemned” to fallibility? If one puts effort into detecting and correcting errors, then one can deal with errors effectively and have a nice life and modern science. There’s nothing miserable about the ongoing need for critical consideration of ideas.

In information theory, there are methods of communicating with arbitrarily high (though not 100%) reliability over channels with a permanent situation of random errors. The mathematical theory allows dealing with error rates up to but not including 50%! In practice, error correction techniques do not reach the mathematical limits, but are still highly effective for enabling e.g. the modern world with hard disks and internet communications. (Source: Feynman Lectures On Computation, ch. 4.3, p. 107)

The situation is similar in epistemology. Error correction methods like critical discussion don't offer any 100% guarantees, nor any quantifiable guarantees, but are still effective.

5. Critical rationalists leave themselves open to the charge of frivolity if they maintain that the 'sources of ideas aren't very important'. How is scientific progress possible without some 'knowledge' of ideas from the past?

Learning about and building on old ideas is fine.

The basic point here is to judge an idea by what it says, rather than by who said it or how he came up with it.

You may learn about people from the past because you find it interesting or inspiring, or in order to use contextual information to better understand their ideas. For example, I read biographies of William Godwin, his family, and Edmund Burke, in order to better understand Godwin’s philosophy ideas (and because it’s interesting and useful information).

6. Why must we be tolerant with, say, totalitarians? Do you really believe that Hitler could be defeated through argumentation?

I think Hitler could easily have been stopped without violence if various people had better ideas early enough in the process (e.g. starting at the beginning of WWI). And similarly the key to our current struggles with violent Islam is philosophical education –- proudly standing up for the right values. The mistaken ideas of our leaders (and most citizens) is what lets evil flourish.

7. One of the most tendentious propositions in philosophy is 'There is a real world.' Popper's 'realism' is Platonic.

So what if it's "tendentious"? What's the point of saying that? Is that intended to argue some point?

Popper isn't a Platonist and his position is that there is a real, objective reality and we can know about it. I was merely stating his position. Sample quote (Objective Knowledge, ch. 2.3, p. 36):

And Reid, with whom I share adherence to realism and to common sense, thought that we had some very direct, immediate, and secure perception of external, objective reality.

Popper's view is that there is an external, objective reality, and we can know about it. However, all our observations are theory-laden – we have to think and interpret in order to figure out what exists.

8. How can an idea be a mistake if its source is irrelevant?

Its content can be mistaken. E.g. "2+3=6" is false regardless of who writes it.

RS may be thinking of a statement like, "It is noon now." Whether that's true depends on the context of the statement, such as what time it is and what language it's written in. Using context to understand the meaning/content of a statement, and then judging by the meaning/content, is totally different than judging an idea by its source (such as judging an idea to be true or probably true because an authority said it, or because the idea was created by attempting to follow the scientific method).

9. One of the many stupid things Popper said was 'All Life is Problem Solving'. Is having sexual intercourse problem-solving? Is listening to Mozart problem-solving?

Yes.

RS calls it stupid because he don't understand it. He doesn't know what Popper means by the phrase "problem solving". Instead of finding out Popper's meaning, RS interpreted that phrase in his own terminology, found it didn't work, and stopped there. That's a serious methodological error.

Having sex helps people solve problems related to social status and social role, as well as problems related to the pursuit of happiness.

Listening to Mozart helps people solve the problem of enjoying their life.

The terminology issue is why I included multiple paragraphs explaining what CR means in my article. For example, I wrote, "[A problem] can be answering a question, pursuing a goal, or fixing something broken. Any kind of learning, doing, accomplishing or improving. Problems are opportunities for something to be better."

Despite this, RS still interpreted according to his own standard terminology. Understanding other perspectives, frameworks and terminology requires effort but is worthwhile.

The comment RS is replying to comes later and reads:

Solving problems always leads to a new situation where there’s new problems you can work on to make things even better. Life is an infinite journey. There’s no end point with nothing left to do or learn. As Popper titled a book, All Life is Problem Solving.

I brought up All Life is Problem Solving because part of its meaning is that we don't run out of problems.

10. 'All problems can be solved if you know how' is a tautology and has no contingent consequences.

It's not a tautology because there's an alternative view (which is actually far more popular than the CR view). The alternative is that there exist insoluble problems (they couldn't be solved no matter what knowledge you had). If you think that alternative view is wrong on a priori logical grounds, I disagree, I think it depends on the laws of physics.

11. 'Knowledge is power' entails 'power is knowledge' which is clearly false as an empirical generalisation.

"Knowledge is power" is a well known phrase associated with the Enlightenment. It has a non-literal meaning which RS isn't engaging with. See e.g. Wikipedia: Scientia potentia est.

I would be very surprised if RS is unfamiliar with this phrase. I don't know why he chose to split hairs about it instead of responding to what I meant.

12. 'If you have a correct solution, then your actions will work' is a tautology.

It's useful to point out because some people wouldn't think of it. If I omitted that sentence, some readers would be confused.

13. 'Observations play no formal role in creating ideas' is clearly false. Semmelweis based his idea about childbirth fever on observations and inductive inferences therefrom.

RS states the CR view is "clearly false". That's the fallacy of begging the question. Whether it's false is one of the things being debated.

Rather than assume CR is wrong, RS should learn or ask what CR's interpretation of that example is (and more broadly CR's take on scientific discovery). Popper explained this in his books, at length, including going through a variety of examples from the history of science, so there shouldn't be any mystery here about CR's position.

I don't think discussing this example is a good idea because it's full of historical details which distract from explaining issues like why induction is a myth and what can be done instead. If RS understood CR's position on those issues, then he could easily answer the Semmelweis example himself. It poses no particular challenge for CR.

Anyone who can't explain the Semmelweis example in CR terms is not adequately familiar with CR to reject CR. You have to know what CR would say about a scientific discovery like that before you decide CR is "clearly false".

14. 'Knowledge cannot exist outside human minds'. Of course it can if there are no human minds. I agree with Thomas Szasz who, in 'The Meaning of Mind' argued that while we are minded (mind the step) we do not have minds. 'Mind' should only be used as a verb, never as a noun. Popper's mind-body dualism is bad enough, but his pluralism is embarrassing.

I wrote "Knowledge can exist outside human minds." and this changes "can" to "cannot". RS, please use copy/paste for quotes to avoid misquotes.

I'm not a dualist.

It's fine to read my statement as "Knowledge can exist outside human brains" or outside people entirely. The point is knowledge can exist separate from an intelligent or knowing entity.

15. 'A dog's eyes contain knowledge'. I don't understand this since to know x is to know that x is true. Since truth is propositional, dogs don't have to deal with issues of truth. Lucky dogs!

CR disagrees with RS about what knowledge is, and claims e.g. that there is knowledge in books and in genes. Knowledge in genes has nothing to do with a dog knowing anything.

RS, what is your answer to Paley's problem? And what do you think genetic evolution creates?

16. Your use of 'knowledge' is somewhat eccentric if you claim that trees know that x.

I don't claim trees know anything, I claim that the genes in trees have knowledge of how to construct tree cells.

CR acknowledges its view of knowledge is non-standard, but nevertheless considers it correct and important.

17. 'Knowledge is created by evolution' is a tautology if we accept a liberal interpretation of 'created'. If we do not and we assume strict causation, it is false.

That knowledge can be created by evolution is contingent on the laws of physics, not tautological. RS does not state what the "liberal interpretation" he refers to is, nor what "strict causation" refers to, so I don't know how to answer further besides to request that he provide arguments on the matter (preferably arguments that would persuade me that RS understands evolution).

18. Ideas cannot literally replicate themselves.

This is an unargued assertion. Literally, they can. I think RS is simply concluding something is wrong because he doesn't understand it, which is a methodological error.

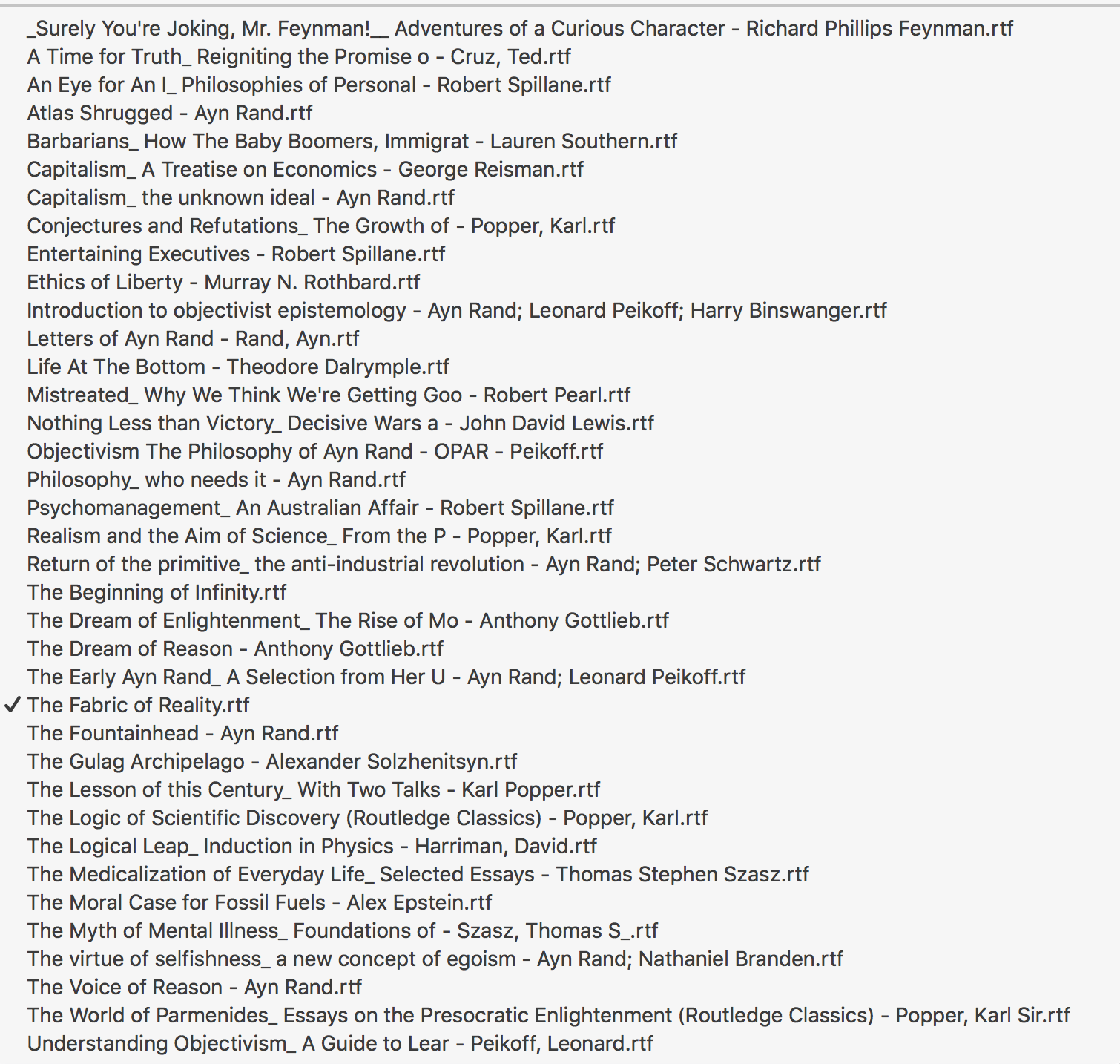

David Deutsch has explained this matter in The Fabric of Reality, ch. 8:

a replicator is any entity that causes certain environments to copy it.

...

I shall also use the term niche for the set of all possible environments which a given replicator would cause to make copies of it....

Not everything that can be copied is a replicator. A replicator causes its environment to copy it: that is, it contributes causally to its own copying. (My terminology differs slightly from that used by Dawkins. Anything that is copied, for whatever reason, he calls a replicator. What I call a replicator he would call an active replicator.) What it means in general to contribute causally to something is an issue to which I shall return, but what I mean here is that the presence and specific physical form of the replicator makes a difference to whether copying takes place or not. In other words, the replicator is copied if it is present, but if it were replaced by almost any other object, even a rather similar one, that object would not be copied.

...

Genes embody knowledge about their niches.

...

It is the survival of knowledge, and not necessarily of the gene or any other physical object, that is the common factor between replicating and non-replicating genes. So, strictly speaking, it is a piece of knowledge rather than a physical object that is or is not adapted to a certain niche. If it is adapted, then it has the property that once it is embodied in that niche, it will tend to remain so.

...

But now we have come almost full circle. We can see that the ancient idea that living matter has special physical properties was almost true: it is not living matter but knowledge-bearing matter that is physically special. Within one universe it looks irregular; across universes it has a regular structure, like a crystal in the multiverse.

Add to this that ideas exist physically in brain matter, (in the same way data can be stored on computer disks), and they do cause their own replication.

Understanding evolution in a precise, modern way was Deutsch's largest contribution to CR.

I don't expect RS to understand this material from these brief quotes. It's complicated. I'm trying to give an indication that there's substance here that could be learned. If he wants to understand it, he'll have to read Deutsch's books (there's even more material about memes in The Beginning of Infinity) or ask a lot of questions. I do hope he'll stop saying this is false while he doesn't understand it.

19. You claim that CR 'works'. According to what criteria - logical? empirical? pragmatic? If it is pragmatism - or what Stove calls the American philosophy of self-indulgence' - then all philosophies, religions and superstitions 'work' (for their believers).

CR works logically, empirically, and practically. That is, there's no logical, empirical or practical refutation of its effectiveness. (I'm staying away from the word "pragmatic" on purpose. No thanks!)

What CR works to do, primarily, is create knowledge. The way I judge that CR works is by looking at the problems it claims to solve, how it claims to solves them, and critically considering whether its methods would work (meaning succeed at solving those problems).

CR offers a conception of what knowledge is and what methods create it (guesses and criticism – evolution). CR offers substantial detail on the matter. I know of no non-refuted criticism of the ability of CR's methods to create knowledge as CR defines knowledge.

There's a further issue of whether CR has the right goals. We can all agree we want "knowledge" in some sense, but is CR's conception of knowledge actually the thing we want? Not for everyone, e.g. infallibilists. But CR explains why conjectural knowledge is the right conception of knowledge to pursue, which I don't know any non-refuted criticism of. Further, there are no viable rival conceptions of knowledge that anyone knows how to pursue. Basically, all other conceptions of knowledge are either vague or wrong (e.g. infallibilist). This claim depends on a bunch of arguments – RS if you state your conception of knowledge then I'll comment on it.

20. You are right to say that '90% certain' is an oxymoron. But so is 'conjectural knowledge'.

Here RS interprets "knowledge" and perhaps also "conjectural" in his own terminology, rather than learning what CR means.

The most important part of CR's conception of knowledge is that fallible ideas can be knowledge. Conjectures are fallible.

"Conjectural knowledge" is also an anti-authoritarian concept. Popper is saying that mere guesses (even myths) can be knowledge (if they solve a problem and are subjected to critical scrutiny). An idea doesn't have to be created by an authority-granting method (e.g. deduction, induction, abduction, "the scientific method", etc) or come from an authority-granting source (e.g. a famous scientist) in order to be knowledge.

21. 'Actually, the possibility for further progress is a good thing' is a value judgement. But how can progress be a feature of CR? Was not Thomas Kuhn right to claim that Popper's position leads to rampant relativism (as Kuhn's does).

No, Popper isn't a relativist about anything. Popper wrote a ton about progress and took the position that progress is possible, objective and desirable. (E.g. "Equating rationality with the critical attitude, we look for theories which, however fallible, progress beyond their predecessors" from C&R.) And Popper thought we have objective knowledge, including about value judgements and morality. Some of Popper's comments on the matter in The World of Parmenides:

Every rational discussion, that is, every discussion devoted to the search for truth, is based on principles, which in actual fact are ethical principles.

...

All this shows that ethical principles form the basis of science. The most important of all such ethical principles is the principle that objective truth is the fundamental regulative idea of all rational discussion. Further ethical principles embody our commitment to the search for truth and the idea of approximation to truth; and the importance of intellectual integrity and of fallibility, which lead us to a self-critical attitude and to toleration. It is also very important that we can learn in the field of ethics.

...

Should this new ethics [that Popper proposes] turn out to be a better guide for human conduct than the traditional ethics of the intellectual professions ... then I may be allowed to claim that new things can be learnt even in the field of ethics.

...

in the field of ethics too, one can put forward suggestions which may be discussed and improved by critical discussion

In CR's view, the ability to learn in a field requires that there's objective knowledge in that field. Under relativism, you can't learn since there's no mistakes to correct and no objective truth to seek. So Popper thinks there is objective ethical knowledge.

22. Your claim that 'induction works by inducing' applies also to 'deduction works by deducing'.

The statement "deduction works by deducing" would be a bad argument for deduction or explanation of how deduction works.

Inductivists routinely state that induction works by generalizing or extrapolating from observation and think they've explained how to do induction (rather than recognizing the relation of their statement to "induction works by inducing").

23. Inductivists do have an answer for you. Stove has argued, correctly in my view, that there are good reasons to believe inductively-derived propositions. I paraphrase from my book 'An Eye for an I' (pp.183-4) for your readers who have no knowledge of my book.

'Hume's scepticism about induction - that it is illogical and hence irrational and unreasonable - is the basis for his scepticism about science. His two main propositions are: inference from experience is not deductive; it is therefore a purely irrational process. The first proposition is irrefutable. 'Some observed ravens are black, therefore all ravens are black' is an invalid argument: this is the 'fallibility of induction.' But the second proposition is untenable since it assumes that all rational inference is deductive. Since 'rational' means 'agreeable to reason', it is obvious that our use of reason often ignores deduction and emphasises the facts of experience and inferences therefrom.

Stove defends induction from Hume's scepticism by arguing that scepticism about induction is the result of the 'fallibility of induction' and the assumption that deduction is the only form of rational argument. The result is inductive scepticism, which is that no proposition about the observed is a reason to believe a contingent proposition about the unobserved. The fallibility of induction, on its own, does not produce inductive scepticism because from the fact that inductive arguments are invalid it does not follow that something we observe gives us no reason to believe something we have not yet observed. If all our experience of flames is that they burn, this does give us a reason for assuming that we will get burned if we put our hand into some as yet unobserved flame. This is not a logically deducible reason but it is still a good reason. But once the fallibility of induction is joined with the deductivist assumption that the only acceptable reasons are deductive ones, inductive scepticism does indeed follow.

Hume's scepticism about science is the result of his general inductive scepticism combined with his commitment to empiricism, which holds that any reason to believe a contingent proposition about the unobserved is a proposition about the observed. So the general proposition about empiricism needs to be joined with inductive scepticism to produce Hume's conclusion because some people believe that we can know the unobserved by non-empirical means, such as faith or revelation. As an empiricist Hume rules these means out as proper grounds for belief. So to assert the deductivist viewpoint is to assert a necessary truth, that is, something that is trivially true not because of any way the world is organised but because of nothing more than the meanings of the terms used in it. When sceptics claim that a flame found tomorrow might not be hot like those of the past, they have no genuine reason for this doubt, only a trivial necessary truth.'

What, then, is the bearing of 'all observed ravens have been black' on the theory 'all ravens are black'? Stove's answer is based on an idea of American philosopher Donald Cary Williams, which is to reduce inductive inference to the inference from proportions in a population. It is a mathematical fact that the great majority of large samples of a population are close to the population in composition. In the case of the ravens, the observations are probably a fair sample of the unobserved ravens. This applies equally in the case where the sample is of past observations and the population includes future ones. Thus, probable inferences are always relative to the available evidence.

The claim "there are good reasons to believe inductively-derived propositions" doesn't address Popper's arguments that inductively-derived propositions don't exist.

Any finite set of facts or observations is compatible with infinitely many different ideas. So which idea(s) does one induce?

Note that this argument is not about the "fallibility of induction". So Stove is mistaken when he says that's the source of skepticism of induction. (No doubt it's a source of some skepticism of induction, but not of CR's.) The claim that deduction is the only form of rational argument is also not CR's position. So Stove isn't answering CR. Yet RS said this was an inductivist answer to me.

This is typical. I had an objection to the first sentence following "Inductivists do have an answer for you." It made an assumption I consider false. It then proceeded to build on that assumption rather than answer me.

Where RS writes, "it is still a good reason", no statement of why it's a good reason or in what sense it's "good" or why being good in that sense matters is given. Avoiding some technical details, CR says approximately that it's a good reason because we don't have a criticism of it, rather than for an inductive reason. Why does no criticism matter? What's good about that? Better an idea you don't see anything wrong with than one you do see something wrong with.

Nothing in the paragraphs answers CR. They just demonstrate unfamiliarity with CR's standard arguments. Consider:

When sceptics claim that a flame found tomorrow might not be hot like those of the past, they have no genuine reason for this doubt, only a trivial necessary truth.

Many things in the future are different than the past. So one has to understand explanations of in what ways the future will resemble the past, and in what ways it won't. Induction offers no help with this project. Induction doesn't tell us in which ways the future will resemble the past and in which ways it won't (or in which ways the unobserved resembles the observed and in which ways it doesn't). But explanations (which can be improved with critical discussion) do tell us this.

For example, modern science has an explanation of what the sun is made of (mostly hydrogen and helium), its mass (4.385e30 lbs), why it burns (nuclear fusion), etc. These explanations let us understand in what respects the sun will be similar and different tomorrow, when it will burn out, what physical processes would change the date it burns out, what will happen when it burns out, and so on. Explanations simply aren't inferences from observations using some kind of inductive principle about the future probably resembling the past while ignoring the "in which respects?" question. And the sort of skeptic being argued with in the quote has nothing to do with CR.

I won't get into probability math here (we could do that in the future if desired), but I will mention that Popper already addressed that stuff. And the object of this exercise was to answer CR, but that would take something like going over Popper's arguments about probability (with quotes) and saying why they are mistaken or how to get around them.

24. You state that Popper invented critical rationalism around 1950. I would have thought it was around the mid-1930s.

Inventing CR was an ongoing process so this is approximate. But here are some of the book publication dates:

Objective Knowledge, 1972. Conjectures and Refutations, 1963. Realism and the Aim of Science, 1983 (circulated privately in 1956). The Logic of Scientific Discovery, 1934 (1959 in English). Since I don't consider LScD to be anything like the whole of CR, I chose a later date.

[25.] Your last paragraph is especially unfortunate because you accuse those philosophers who are not critical rationalists (which is most of them) of not understanding 'it enough to argue with it.' With respect Elliot, this is arrogant and ill-informed. Many philosophers understand it only too well and have written learned books on it. Some are broadly sympathetic but critical (David Miller, Anthony O'Hear) while others (Stove, James Franklin) are critical and dismissive. To acknowledge that CR 'isn't very popular, but it can win any debate' is nonsensical and carries the whiff of the 'true believer', which would seem to be self-contradictory for a critical rationalist.

It may be arrogant, but I don't think it's ill-informed. I've researched the matter and don't believe the names you list are counter-examples.

What's nonsensical about an idea which can win in debate, but which most people don't believe? Many scientific ideas have had that status at some time in their history. Ideas commonly start off misunderstood and unpopular, even if there's an advocate who provides arguments which most people later acknowledge were correct.

I think I'm right about CR. I'm fallible, but I know of no flaws or outstanding criticisms of any of my take on CR, so I (tentatively) accept it. I have debated the matter with all critics willing to discuss for a long time. I have sought out criticism from people, books, papers, etc. I've made an energetic effort to find out my mistakes. I haven't found that CR is mistaken. Instead, I've found the critics consistently misunderstand CR, do not provide relevant arguments which address my views, do not address key questions CR raises, and also have nothing to say about Deutsch's books.

I run a public philosophy discussion forum. I have visited every online philosophy discussion forum I could find which might offer relevant discussion and criticism. The results were pathetic. I also routinely contact people who have written relevant material or who just seem smart and potentially willing to discuss. For example, I contacted David Miller and invited him to discuss, but he declined.

Calling this arrogant (Because I think I know something important? Because I think many other people are mistaken?), doesn't refute my interpretation of these life experiences. RS, if you have a proposal for what I should do differently (or a different perspective I should use), I'll be happy to consider it. And if you know of any serious critics of CR who will discuss the matter, please tell me who they are.

None of RS's 25 points were difficult for me to answer. If RS knew of any refutation of CR by any author which I couldn't answer, I would have expected him to be able to pose a difficult challenge for me within 25 comments. But, as usual with everyone, so far nothing RS has said gives even a hint of raising an anti-CR argument which I don't have a pre-existing answer for.