Tips for tracking discussions well:

- Write down a tree diagram (or, equivalently, a bullet point outline with nesting).

- Whenever you write stuff and get a reply, note down anything you’d written which the reply didn’t address. Also note down stuff the other guy said which you didn’t answer. With this method, the open issues are the things on your list plus the stuff in the latest post. (This is simplest in a two person discussion where you take turns writing one message at a time.)

- Get better at remembering stuff in discussions.

More on (1) and (3) below.

Trees and Outlines

Here’s an explanation of discussion tree diagrams with an example. And here’s another explanation below (actually written first, even though posted second):

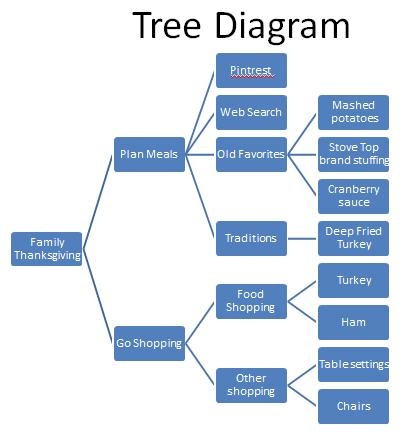

Here’s an example tree diagram:

You can create tree diagrams with pen and paper or with various software options (some are mentioned in my other post on discussion trees).

Trees like this are always equivalent to outlines with nesting. Nesting X under Y in an outline is the same as drawing a line from X to Y in a tree (with Y below or to the right of X, depending on whether it’s a top-to-bottom or left-to-right tree). You can do both trees and outlines to get comfortable with how they’re the same. Both represent parent/child relationships (that’s standard terminology) where some things are attached underneath others. For discussion trees, replies are the children which you put under the thing they reply to. The “parent comment”, like on Reddit, is the thing being replied to.

Example outline which is equivalent to the tree:

- Family Thanksgiving

- Plan Meals

- Pintrest

- Web Search

- Old Favorites

- Mashed Potatoes

- Stove Top brand stuffing

- Cranberry sauce

- Traditions

- Deep Fried Turkey

- Go Shopping

- Food Shopping

- Turkey

- Ham

- Other Shopping

- Table settings

- Chairs

- Food Shopping

- Plan Meals

To outline well, you need to be able to write short summaries. E.g. take a three paragraph argument and condense it to one sentence for your outline. This is a skill you can practice by itself.

Remembering Stuff

With practice you can remember more stuff without writing it down. This isn’t automatic. It’s something you can work on or not. It helps to try to remember stuff, and to reread the conversation to look up stuff you did not remember. And it helps to consider it important when someone refers to something you’d forgotten, and go reread it and take note of your memory error (try to find patterns and causes for your memory errors).

A related thing to practice is remembering what you say or read in general. You can quiz yourself on this. After reading something, try to write down what it said without looking at it. Start with shorter stuff (or break longer things into parts, like reading one paragraph at a time). If you get good at this and find it easy, do it with longer stuff and/or do it after a delay (can you remember it 5 minutes later without rereading? 20min? 3 hours? 3 days? 3 weeks?). And do it with your own stuff too. After you write something, try to write the same thing again later. See how accurate you can be for longer stuff and after longer wait times. You can do this with spoken words that you hear or speak, but you won’t be able to check your accuracy unless they were recorded.

People often don’t clearly know what they just read, or can’t keep it in their head long enough to write a reply (e.g. if you spend 30min writing a reply, you need to either remember the text you’re replying to that long or reread it at least once to refresh your memory). People often partially forget, partially remember, and don’t realize the accuracy loss happened (and don’t realize they should selectively reread key parts to double check that they remembered those accurately).

It’s also good if you can clearly remember what you said 1-3 days ago, which someone just replied to. You’ll often get replies the next day after you write something. And to the extent you don’t remember, it’s important to realize you don’t remember, recognize you don’t know, and reread. It’s also good if you can remember details from earlier in the conversation, which could be a week or more ago – and if you don’t, you better review relevant parts of the conversation back to the beginning if you want to write high quality comments which build on prior discussion text.

It’s easier to remember, especially for older material, if you have notes. If you keep an outline, tree and/or notes on what was said (including copy/pasting key quotes to your notes file), it’s easier to remember. If you do that for a while, it’ll be easier to remember without the notes. The notes are partly like training wheels that help you learn to remember stuff (it helps you break the remembering down into parts – instead of remembering everything, you partly read your notes and partly remember stuff that isn’t in your notes, so this way you have less to remember, so it’s easier, which makes good practice because you’re working on part of the skill instead of the whole skill at once).

However, notes and outlines aren’t just like training wheels, they are also good things which you shouldn’t expect to ever entirely stop using. They’re useful for practice but also just useful. With practice, you may learn to use them less but still use them. Or you might use them more with practice as you get better at creating and using them. Remembering everything in your head, instead of using tools, is not necessarily a good thing. Remembering some stuff is useful but there is some stuff you shouldn’t be trying to remember. Remembering basically means temporarily memorizing. The anti-memorization ideas you already know about have some relevance.

Also, notes, trees and outlines are useful for communicating with others. You can use them in the discussion. If the other person gets lost and confused, or there is a disagreement about what happened in the discussion, you can share your outlines/trees/notes to communicate your view of what happened. This can remind the person and help them, or it can be compared with their outlines/trees/notes to figure out specifically where you differ (find somewhere your outline is different than theirs, go reread the original text, find and fix someone’s error).

Sharing discussion trees/outlines is a good way to help figure out what’s going on in difficult discussions that become chaotic. Most people don’t have the tree in their head, didn’t try to keep notes, and also can’t (don’t know how to) go back and create the tree for the current discussion. Sadly, people also commonly don’t want to review a discussion and create a tree. That’s because it’s work and people are lazy and/or think discussion should be much easier than it is. People have incorrect expectations about what it takes to discuss well, so if it’s not working with ease they blame the other person or they blame bad luck and incompatibility, but they don’t usually seem to think the thing to do is increase their skill and put in more effort.

Many people avoid resuming conversations after the first day – they want to talk a bunch at once (e.g. talk for an hour) and then never continue later. This is a really common way trying to discuss issues with people sucks and fails. It’s hard to get anywhere with people like this. A major cause of this problem is their bad memory skill. They don’t want to continue the discussion the next day because they forgot most of what was said. To be good at truth seeking, you need to be able to discuss things over time, which requires both memory and willingness to review some stuff sometimes.

More Complicated Discussions

This section is some more advanced and optional material.

A discussion tree can actually be a directed acyclic graph (DAG), not a tree, because one argument can reply to 2+ parents. In that case, a bullet point style outline won’t represent it. However, you usually can make a good, useful discussion tree without doing that.

Directed means the connections between nodes go in a particular direction (parent and child) instead of being symmetric connections. Nodes are places on the graph that can be connected, they are parents or children – specifically they are discussion statements. E.g. “Go Shopping” and “Cranberry Sauce” are nodes. Acyclic means the graph isn’t allowed to go in circles. You can’t have node A be a child of B which is a child of C which is a child of A.

A DAG can always be put in a topological ordering (linear order, 1-dimensional order, similar to an outline or list) which could maybe be useful. Cycles ruin that ordering but aren’t allowed because no statement in a discussion can be a child of a statement that was made at a later time. A child of node N is a reply to N. Because statements don’t reply into the future (and we can treat all statements as being added one at a time in some order), cycles are avoided.

Statements do reply into the future in a sense. Sometimes we preemptively address arguments. One way to handle this is to add a new argument, C, “A already addressed B preemptively”, as a child of B. This gets into the “last word” problem. Even if you preemptively address stuff, people just ignore you or make tiny changes to try to make a new comment required. The big picture way to deal with this is by criticizing their methodology – they are creating a pattern of errors which need to be addressed as a pattern instead of individually.

Messages (6)

This completely fails to account for inexplicit knowledge that can be contained within a conversation.

you should understand the explicit knowledge as a starting point. it's easier and the inexplicit, implied and between the lines stuff refers to it.

if u can't understand the objective, logical aspects of the conversation, you are in a bad position to understand other aspects.

the blog post didn't present itself as complete. it's offering some info and tools. the things they help with are important both generally and to the specific goal of dealing with inexplicit knowledge well.

curi, would you ever debate someone on video or do you only do it on your email group or this website.

example: https://youtu.be/zf1ugCMK_v8

#14182 Yes I would.

Discussion Tree Article Draft 3

I posted this to FI, Nov 25, 2019. Making it easier to find because I don't expect to finish this article soon.

# Discussion Trees

A discussion tree is tool for illustrating and understanding discussions. It’s a tree diagram meant to outline/summarize the ideas and visually show the discussion structure (what is a reply to what, what was or wasn’t replied to). Trees help objectively figure out the current state of the debate/discussion and help reach a conclusion rationally.

Explaining how discussion trees work also serves as a way of explaining how rational discussion works.

All discussion is externalized thought, and a large portion of internal thought is self-discussion (discussing with yourself). Consequently, understanding rational discussion is crucial to understanding rational thinking.

Creating discussion trees involves *breaking complex ideas into smaller parts* and *specifying relationships between ideas*. These are essential parts of thinking.

## Terminology

There are useful words for talking about trees. Each box in a discussion tree is called a *node*. A node can be e.g. a statement, claim, argument, explanation, question or comment.

Lines indicate *relationships* between nodes. Nodes 2 and 5 are *parent* and *child* (2 is the parent, 5 is the child). Use child nodes to *reply* to the idea/argument in the parent.

A *descendant* is a child, grandchild, great grandchild, and so on – any node linked by one or more child relationships. The opposite, a node linked by parent relationships, is an *ancestor*.

Node 1 is the *root* (or *head*) node because it has no parent. It’s the start. Nodes 4, 6, 7 and 8 are *leaf nodes* because they have no children. Leaves are the outside of the tree. They’re notable because they’re *unanswered* – there is no reply to a leaf.

A *subtree* (or *branch*) is a node and its descendants. It’s a tree starting with a different root. For large trees, it’s often useful to focus on understanding or discussing one branch at a time. A *group* of nodes is a partial subtree: some nodes of a subtree (and their descendants) can optionally be left out.

The *level* of a node is its distance from the root. The root is the topic (level 0). Node 2 is at level 1 (a 1st response to the topic) and node 5 is at level 2 (a response to a response to the topic). In two person discussions, it’s common that one person says everything on an odd numbered level and the other person says everything on an even numbered level.

A node is *resolved* – a *conclusion* about it has been reached – if the people in the discussion *agree* on whether it’s correct or incorrect. Mark resolutions on the tree. You can also resolve nodes in your own opinion. You can mark on the tree the conclusions you’ve reached, the conclusions the other guy has reached, and also the conclusions you both agree on.

## Thinking In Parts

Consider a sentence like “I think W because X, Y and Z.” This single sentence contains four ideas. A tree would represent it with four nodes. Trees encourage people to separate their ideas so they can look at each idea by itself. Trees also let people conveniently see what ideas are related to each other, e.g. W is an argument against some other idea, V, and V may have several parts and be an argument against U.

For breaking ideas into parts, try writing out the idea with simple sentences using no conjunctions or punctuation. Then give a node to each sentence. Alternatively, write your ideas normally but then look for different parts. Conjunctions like “because”, “if”, “or”, “but” and “and” are the biggest giveaways that there are multiple ideas put together.

Writing (bullet) point form notes is another way to break ideas into parts. Conveniently, point form notes (with indenting for sub-points) can be imported into mind mapping apps and automatically converted to a tree.

Multi-part ideas form a group. The head (root) of that group is the leader. It says the main point of the group, e.g. to claim W or argue against W. The other nodes in the group help support that purpose, e.g. by providing additional reasoning, info, details, explanation, answers to potential questions and links to sources (e.g. books or webpages with more info).

### Minimal Ideas

How small a part or chunk should ideas be split into?

The minimum is the smallest version of an idea which makes sense as a single thought. Can it stand on its own, *independently* and autonomously? This is approximately one simple sentence with one verb. English and other languages are designed with the concept of a sentence being one thought, and if you don’t use the stuff that makes sentences more complicated, then you get roughly the minimum amount of stuff for a meaningful thought.

A single noun, like “cat”, is too small. What about the cat? Similarly a verb, like “want”, is too small. Who wants something? What do they want? “My cat wants tuna.” is a pretty minimal English sentence that is enough to express a meaningful thought.

Connecting multiple independent ideas allows for creating more complex structures. Complex sentences, paragraphs and whole articles do this. They build up more sophisticated concepts by combining many simpler ideas. (Similarly, ideas are made by combining simpler parts, like “tuna”, which are less than one idea. “Tuna” requires some context, some filling in the blanks with guesses, to convey a meaningful thought. E.g. if you imagine an open can of tuna sitting on a table, you’re adding information that isn’t in the word “tuna”. Tuna could be at any location, in any form, e.g. a currently living tuna fish in outer space about to fall into a black hole. But even that is making assumptions. In the sentence “I wish I had tuna” there isn’t any tuna in reality, so imagining some tuna existing in reality doesn’t fit that use of the word.)

You can break ideas into larger parts than the minimum. In general, when there are problems, e.g. people disagreeing, break ideas down more. But when people understand and agree on some point, then it’s good enough and you can focus your attention elsewhere. However, people underestimate how much they should break things down, and overestimate what they understand and agree with, so err on the side of breaking ideas into smaller parts than you think you should.

### Atomic Metaphor

A minimal, indivisible part is called an “atom”. That’s what the word means even though science has discovered that atoms are actually made of sub-atomic particles like neutrons. Combining atoms gets a molecule. Combining molecules can make a cell. Combining a huge number of sells can make an organ like a heart. Combining organs and a few other things can make an animal.

You can use the atomic model as a metaphor to think about ideas. A minimal idea is an atom. A paragraph is a molecule. A section is an article. A chapter is an organ. A book is an animal. This is how smaller parts combine to create a more complex and greater whole.

Atoms combine into molecules with *atomic bonds*. There are both atoms and relationships connecting atoms. Similarly, molecules combine with molecular bonds (which basically involve some of their atoms connecting with a bond). A cell has a *cell wall* which keeps everything together in one group with a clear division between the group (cell) and everything else (the external environment and other objects). Organs too have outer edges and have their cells attached together, and animals have skin.

Discussion trees are about, at the same time:

1. The nodes (atoms).

2. The connections between nodes (atoms bonds).

3. Groups of nodes (molecules).

4. The connections between groups (molecular bonds).

5. Groups of groups (cells) and other higher level structures (e.g. groups of groups of groups, which is organs).

6. The relationships between higher level groups (like multiple cells being attached together).

### Building Block Metaphor

Another useful metaphor is that simple ideas are building blocks and our conclusions are buildings (could be a one story building or a skyscraper depending on how complicated it is).

We combine building blocks in intermediate stages, e.g. we combine many rocks (and some other stuff) to make concrete. Then the concrete is used to make a pillar which is one one the supports to create the next level, which is one of the levels in the building.

Buildings are made of many little parts which are combined into bigger and bigger pieces of the building (like a wall, a room, or a whole floor). Again we see building up complex from many smaller parts which are connected together into medium parts which are connected together into big parts (so the big part consists of many small parts).

### Organized Thinking

Organizing thinking involves figuring out a good simplest level for what you’re doing. Examine things at that level detail. For more complicated things, break them into parts to reach the right level of detail so you can understand them in a simpler way. Figuring out how something is a combination of simpler parts lets you focus on one part at a time to learn and understand it and also to judge the correctness of the part. Looking at simpler parts also lets you look at and understand the relationships between those parts.

If it’s not working, try considering some things as a simpler level. That’s a good way to get unstuck, and overcomplicating things (without enough understanding to deal with it) is a common weakness that people in our society have.

You can always break things down more until you get to simple sentences. And even then, you can break those into things that are less than a thought (words) and consider those individually. Sometimes discussions fail because people have incompatible understandings of a word.

Many ideas that adults deal with in their lives are quite complicated. They can be broken into parts which are broken into parts that can be broken into parts, and so on, several more times, before getting to simple sentences. A common error is trying to talk about the complicated ideas without understanding the simpler ideas they’re built up from, and how those simpler ideas are organized (what’s related to what, what’s built out of what).

**Tip:** You can sometimes skip writing out a tree for our knowledge if you *could* write that tree. If you understand something well enough that a tree wouldn’t be very hard to make, then maybe you don’t need to write out the tree. But if you *couldn’t* create the tree, or would find it hard, then that means you’d learn a lot from the tree.

## Decisive Arguments

A node or group can be an *argument*. An argument either positively supports or negatively criticizes its parent node. For a group, the parent node is the parent of the group’s root node.

*Decisive* (also called conclusive or essential) arguments argue that the parent is incorrect. At least one of the parent or argument must be incorrect. They can’t both be correct. They’re incompatible. If a decisive argument node or group is resolved as correct, then its parent must be resolved as incorrect. The parent is *refuted* by that criticism.

Positive arguments, inconclusive negative arguments and explanatory comments aren’t decisive arguments.

Decisive arguments shouldn’t be ignored. They’re mandatory to address. Other nodes don’t necessarily have to be dealt with. You can judge a non-decisive node is uninteresting and unimportant (and explain why). But with a decisive argument, saying it’s unimportant is an inappropriate response (unless you think its parent, the thing it’s criticizing, is unimportant). E.g. a reason that your claim is incorrect is important and needs to be evaluated.

*Figuring out which arguments are decisive or not, and focusing making and resolving decisive arguments, is the most effective way to reach a conclusion. That’s the proper focus of **debate**. In the alternative, if your focus is on **learning**, then decisive arguments are less important and everything else, especially questions, explanations and information, are more important.*

Marking/labelling decisive argument nodes or groups, or indecisive/inessential nodes and groups, is one of the standard ways to improve and better understand a discussion tree. You can mark with e.g. colors, words, icons or drawing lines around groups.

A question counts as a decisive argument if not having an answer to the question would mean the idea doesn’t work.

### Debate Trees

A debate tree is a type of discussion tree. Besides the topic (root), it contains only decisive arguments. You can convert a discussion tree to a debate tree by deleting all indecisive parts.

In a debate tree, resolving the root requires resolving all nodes. Resolving a subtree requires resolving all nodes in that subtree. Even if you don’t resolve everything, you can often still resolve some subtrees. *Resolving decisive arguments is the primary goal of debate.*

Debate trees help you objectively evaluate the current *state of the debate* on some topic. What are the decisive arguments and what conclusions make sense given those arguments?

To dispute a decisive argument in a debate tree, a *counter-argument* is needed. Take any node in the argument and create a child node with a decisive criticism.

### Resolving Nodes

Resolving an argument as correct requires resolving the parent as incorrect.

When resolving a node as incorrect, check if that node is part of a group. If it’s a multi-part argument, then the whole argument is wrong if one part is wrong. So resolve the whole group as incorrect.

If all arguments against an idea are resolved as incorrect, it doesn’t mean the idea is correct. However, if no one can think of any correct or unresolved argument against an idea, then the idea should be tentatively accepted. People are welcome to take some time to consider, but if they can’t come up with any criticism, then they should accept the idea.

What if there are multiple incompatible ideas with no criticisms? When there are alternatives, how do we choose? If two ideas X and Y contradict each other and both fail to explain why they’re correct, then they’re both inadequate. Criticize each of them for reaching a conclusion that is more specific than their arguments allow. Idea X made X claim about reality even though its reasoning was only good enough to reach the conclusion that X *or* Y is how reality is. Accept instead the idea Z which says that X or Y could be correct. Z is the single known idea about this topic with no criticism of it.

### Reaching Conclusions in Subtrees

Many discussions or debates don’t reach conclusions. People bicker endlessly and the topic keeps changing. A technique that helps is to *focus on resolving one subtree* at a time. Once a node is brought up, only discuss descendants of that node until the node is resolved. During that discussion, when a new node is brought up, again focus only on its descendants until it’s resolved. And so on.

This is called a *depth-first search* because it considers higher numbered (deeper) levels first rather than other subtrees at the same level first (breadth-first). You don’t have to use depth-first every time, but it’s a useful and underrated approach. It especially helps when discussion is chaotic.

### What If My Indecisive Argument Is Important?

First, ideas other than arguments are important and valuable. Explanations of concepts help us understand the world (and help lead to arguments). Second, if your indecisive argument is genuinely important to a debate, you can reformulate it as a decisive argument.

A explanation, piece of information or an indecisive negative argument is useful for brainstorming and inspiration. That is important. But if what you want is a decisive negative argument, you’ve gotta come up with one. Maybe you can come up with a way to change your indecisive argument to be decisive.

If your comment is a positive argument, in addition to using it as inspiration, you can translate it to a negative argument. *All* correct positive arguments can be translated to negative arguments.

Here’s how to translate: A positive argument points out a positive feature of an idea. To get a negative argument, point out how one or more alternative ideas lacks that positive feature. For this argument to be decisive, explain how lacking that positive feature makes the idea incorrect (the idea needs that positive feature to work).

In all cases, you must come up with a decisive negative argument to change the objective state of the debate and contribute to a debate tree. You also must come up with a decisive negative argument to refute anything in any discussion tree.

Note: People often use positive arguments in *informal* discussions without translating them to negative arguments. That’s fine as long as long as everyone understands and agrees. It’s a shortcut. But if anyone disagrees or objects, then the standard way to resolve that disagreement is by translating the positive argument to a negative argument. Don’t insist on using positive arguments when there’s a dispute.

Also, positive arguments are often OK, especially informally, *internally in groups*. The group type (decisive argument or not) is determined by the group’s root node. Positive reasoning can help explain and break into parts a negative argument.

### Changing Your Mind Is OK

Sometimes people agree to resolve a node as correct or incorrect, but then later they think of a new idea or argument and want to make the node unresolved again. This is OK. Disallowing it would discourage anyone from agreeing to resolve a node.

Rather than leaving everything unresolved forever just in case we think of a new argument later (possibly based on new evidence), we *tentatively* resolve nodes. We use our best judgment to reach conclusions when we think we know enough. But we’re allowed to reconsider later. Judgments don’t have to be final.

## Trees Help Organize Discussions

Discussions, including debates, should try to seek the truth. Discussion trees help organize and keep track of discussions, which helps figure out what’s true. Trees help show which ideas are answered or unanswered.

Answered ideas have children which express arguments, doubts, objections, etc. Unanswered ideas have no children, or have only children which have been resolved as incorrect.

Trees are also useful when discussions get confused or chaotic. I can make a discussion tree to share my understanding of the discussion, and you can point out which parts you think don’t match the discussion we had. Or we can both make trees and compare them for differences.

We can discuss by adding nodes to a tree as we go along so we’re keeping the discussion clear and organized the whole time. Or we can create a tree and start adding nodes if a discussion has trouble.

### Objectivity

Regardless of whether you agree or disagree with an argument, present it fairly. This is easier with trees than normal because you’re usually summarizing. You don’t have to give all the details of arguments that you disagree with.

Each side of the debate is an intellectual position (or school of thought) – a group of related ideas that fit together. Don’t associate the sides too strongly with people. People can try to contribute arguments for every position. Everyone’s goal should be to evaluate the ideas and try to figure out a good conclusion. The point of discussion is to help each other do this.

It often helps to color-code or otherwise label nodes based on which side they’re on. This makes argument groupings clearer (multiple connected nodes of the same color are a multi-part argument) and it makes it easier to see criticisms and objections (a child of a different color).

Keep in mind there are usually more than two sides. It’s often helpful to focus on two sides at a time, which keeps things simpler, but remember that there may be other viewpoints. If you finish a tree with two positions, consider if there is another position on the same issue to investigate next.

### Making Trees Alone

You can make discussion trees by yourself. You can use them to help study discussions between other people. E.g. you could read arguments about abortion and put them into a tree. Figure out what’s a decisive argument and what’s a comment. Figure out what’s an unanswered leaf node. Consider which nodes you’re willing to reach a judgment about and resolve. After you begin to understand other people’s arguments, add some nodes and comments of your own. Those activities will help you think and learn.

Creating a discussion tree is also a good way to express your understanding of a topic. You can write all sides of the discussion. Write the important arguments and questions for the other side that you know of, and give your responses. Then you can show the tree to people and ask what you’re missing, rather than starting a discussion from scratch.

You can also use a discussion tree to help figure out a topic by arguing with yourself. If you don’t have a conclusion yet, you can use use the tree to express what you do know and work towards reaching a conclusion.

In general, if you can’t make a tree and reach a conclusion alone, you shouldn’t be debating others. You don’t know what you think so why try to correct other people and argue what they should think? If you don’t already have a conclusive tree, in your opinion, then you shouldn’t do advocacy. Stick to discussions where you ask questions and share ideas.

### Outlining

You can make trees with different levels of detail. Usually it works best to summarize arguments but leave out most of the details. This helps you see an overview of the discussion and its structure. People can refer to source materials for details. E.g. if you have a debate on a web forum, people can look at the forum posts for more details about arguments. Or if your tree relates to some books and articles, people can get the full details from those.

You can write out more detailed arguments in a tree when you find it useful. Sometimes I’ll write a long paragraph in one node. But I don’t find it useful to put a whole 1000 word essay in a node. I’d rather just give the link to it. Alternatively, I’d break the ideas in the essay up into separate pieces and use them for multiple nodes.

Figuring out how to break ideas down into smaller pieces (that still make sense individually) – one node per piece – helps understand ideas better.

### Multiple Trees

When trees get too big, you can put subtrees into separate documents. You can make an overall tree where each node is the name of a subtree. You can also make a mixed tree with some regular nodes and some nodes which refer to subtrees in other documents.

Referring to a tree in another document is like citing a source. Having a group of arguments as a tree in a document lets you reuse them in many future discussions.

Referring to a tree from another document is equivalent to adding all its nodes where the reference is. It’s the same as if you copied over every node one by one. It’s just a shortcut.

## Trees vs. Pro/Con Lists

Pro/con lists are a common tool for people trying to organize the arguments about an issue. Some biased people only care about arguments for “their side”, so they wouldn’t use a pro/con list because one half would be blank. A pro/con list is an improvement over that which helps people be more objective and consider both sides.

Trees have advantages over pro/con lists because they break ideas into parts and show relationships between ideas. Trees show counter-arguments and counter-counter-arguments. Pro/con lists encourage focusing on level 1 arguments.

Pro/con lists don’t help people break their reasoning into smaller, related parts to better understand their thinking. Each point gets one statement and that’s it.

Pro/con lists are partly based on mistaken philosophy ideas about how rational debate works. The idea is to add up the weight of the arguments for each side and whichever side has more weighty arguments wins. The hidden assumption here is that most arguments are inconclusive, so for complex issues there will usually be a bunch of inconclusive arguments on each side. So people try to evaluate how good the inconclusive arguments are and sum them together.

The correct approach to debate is to focus on decisive arguments. Come up with reasons that things can’t be right. An inconclusive argument against X is an argument which is compatible with X being true. Having a bunch of those isn’t good enough. A conclusive argument is one which is adequate to reach a conclusion about some issue (e.g. that a particular claim is mistaken) unless there’s new info or arguments. An inconclusive argument is (by definition) inadequate to reach a conclusion, and having ten of them can’t fix that problem.

Debate trees fit the concept of arguments conclusively refuting other arguments. They focus the discussion on critical thinking. They encourage trying to find mistakes in the ideas (conclusive problems, not irrelevant complaints about minor details).

Pro/con lists aren’t designed for resolving nodes. Debate trees are better at reaching conclusions. Debate trees are also capable of reaching conclusions about subtrees, which is an easier way to get started and is partial progress, while pro/con lists are too all-or-nothing and only focus on reaching a final conclusion all at once.

## Making Trees

There’s software for making discussion trees. I recommend MindNode (Mac, iOS), XMind (Windows, Mac, iOS, Android, Linux), or iThoughts (Windows, Mac, iOS).

## More Info

You can view a complicated tree that I made with MindNode and my discussion tree blog category.

I extensively explain the importance and philosophy of decisive arguments in Yes or No Philosophy.

#15760 In a followup post I shared this additional section I'd written for the article:

### Explaining Relationships

Nodes have words to explain what they mean. Relationships between ideas are represented with a line, not words. This works OK for simple relationships, especially when the words in the node give hints about the relationships. What about complex relationships?

When there’s a complex relationship that needs explaining, use a group of nodes. A counter-argument can have a head node which summarizes the argument, plus some child nodes with facts and claims, plus some other child nodes which explain how the facts and claims work together to make an argument and how that argument relates to the group’s parent that you’re trying to criticize.

Or in a simpler case, you could have a group of two nodes. The first is a claim and the second (its child) gives some reasoning explaining how the claim relates to the claim’s parent. Whenever a relationship isn’t simple enough, you can add nodes explaining.

This doesn’t just apply to critical arguments. Say you make a claim and you have five pieces of evidence related to the claim. But it’s not clear enough why three of those pieces of evidence help the claim. Then for those three, you could add a child node explaining how that evidence relates to the claim.