How To Ask Questions 2

How To Ask Questions 3

How To Ask Questions 4

How To Ask Questions 5

How To Ask Questions 6

Rationally Resolving Conflicts of Ideas

I knew I'd already written a number of explanations on the topic, so I decided to reread them for preparation. While reading them I decided that the topic is hard and it'd be very hard to write a single essay which is good enough for someone to understand it. Maybe if they already had a lot of relevant background knowledge, like knowing Popper, Deutsch or TCS, one essay could work OK. But for an Objectivist audience, or most audiences, I think it'd be really hard.

So I had a different idea I think will work better: gather together multiple essays. This lets people learn about the subject from a bunch of different angles. I think this way will be the most helpful to someone who is interested in understanding this philosophy.

Each link below was chosen selectively. I reread all of them as well as other things that I decided not to include. It may look like a lot, but I don't think you should expect an important new idea in epistemology to be really easy and short to learn. I've put the links in the order I recommend reading them, and included some explanations below.

Instead of one perfect essay – which is impossible – I present instead some variations on a theme.

Update 2017: Buy my Yes or No Philosophy to learn a ton more about this stuff. It has over 6 hours of video and 75 pages of writing. See also this free essay giving a short argument for it.

Update Oct 2016: Read my new Rejecting Gradations of Certainty.

Popper's critical preferences idea is incorrect. It's similar to standard epistemology, but better, but still shares some incorrectness with rival epistemologies. My criticisms of it can be made of any other standard epistemology (including Objectivism) with minor modifications. I explained a related criticism of Objectivism in my prior essay.

Critical Preferences

Critical Preferences and Strong Arguments

The next one helps clarify a relevant epistemology point:

Corroboration

Regress problems are a major issue in epistemology. Understanding the method of rationally resolving conflicts between ideas to get a single idea with no outstanding criticism helps deal with regresses.

Regress Problems

Confused about anything? Maybe these summary pieces will help:

Conflict, Criticism, Learning, Reason

All Problems are Soluble

We Can Always Act on Non-Criticized Ideas

This next piece clarifies an important point:

Criticism is Contextual

Coercion is an important idea to understand. It comes from Taking Children Seriously (TCS), the Popperian educational and parenting philosophy by David Deutsch. TCS's concept of "coercion" is somewhat different than the dictionary, keep in mind that it's our own terminology. TCS also has a concept of a "common preference" (CP). A CP is any way of resolving a problem between people which they all prefer. It is not a compromise; it's only a CP if everyone fully prefers it. The idea of a CP is that it's a preference which everyone shares in common, rather than disagreeing.

CPs are the only way to solve problems. And any non-coercive solution is a CP. CPs turn out to be equivalent to non-coercion. One of my innovations is to understand that these concepts can be extended. It's not just about conflicts between people. It's really about conflicts between ideas, including ideas within the same mind. Thus coercion and CPs are both major ideas in epistemology.

TCS's "most distinctive feature is the idea that it is both possible and desirable to bring up children entirely without doing things to them against their will, or making them do things against their will, and that they are entitled to the same rights, respect and control over their lives as adults." In other words, achieving common preferences, rather than coercion, is possible and desirable.

Don't understand what I'm talking about? Don't worry. Explanations follow:

Taking Children Seriously

Coercion

The next essay explains the method of creating a single idea with no outstanding criticisms to solve problems and how that is always possible and avoids coercion.

Avoiding Coercion

Avoiding Coercion Clarification

This email clarifies some important points about two different types of problems (I call them "human" and "abstract"). It also provides some historical context by commenting on a 2001 David Deutsch email.

Human Problems and Abstract Problems

The next two help clarify a couple things:

Multiple Incompatible Unrefuted Conjectures

Handling Information Overload

Now that you know what coercion is, here's an early explanation of the topic:

Coercion and Critical Preferences

This is an earlier piece covering some of the same ideas in a different way:

Resolving Conflicts of Interest

These pieces have some general introductory overview about how I approach philosophy. They will help put things in context:

Think

Philosophy: What For?

Update: This new piece (July 2017) talks about equivocations and criticizes the evidential continuum: Don't Equivocate

Want to understand more?

Read these essays and dialogs. Read Fallible Ideas. Join my discussion group and actually ask questions.

Asking Good Questions

I'm asked lots of questions. Writing great answers for all of them would take too long.

I prioritize writing answers I consider interesting or important.

Sometimes I give a short answers or a link. Sometimes I suggest that a friend answer a question. But I still don't answer some questions at all.

My first priority is what I want to answer. Secondarily, I'd like to answer questions that the asker cares more about, puts more effort into, and gets more value from.

Sometimes people ask careless questions. Sometimes they barely care what the answer is. Sometimes they lose interest in the topic a couple days later but don't share this fact. Sometimes they could have easily found the answer with Google, but they don't respect my time. Some questions are dead ends where they have no comment on the answer and no followup questions.

I have limited information about how important a question is to you. You can help with this problem by writing better questions. Here are some things you can do to get more attention:

- Ask on the Fallible Ideas discussion group or curi forum (this website). Those are my preferred places to take questions and I give them priority. But don't use FI unless you read the guidelines and format your post correctly.

- State steps you already took to find the answer yourself, and why they didn't work.

- Write well. Use short, simple words, sentences and paragraphs. Clearly mark quotes. Emphasize key points. Do an editing pass to make it clearer and easier to understand. Keep things organized and limit repetition.

- Make it really clear what the question actually is.

- Give specifics. I don't have a solution to "I am sad". That describes millions of different problems. (If you want a very general purpose answer like "Then do problem solving." you can state that you want a general case answer with no specifics.)

- Mention relevant background knowledge you have. If you ask about altruism, I may suggest you read Ayn Rand. If you've already read her, you should have told me!

- Say what kind of answer you're looking for. What are you looking for? What sort of information would you consider an adequate answer?

- Say why you want an answer to this question and what problem it will solve for you. Say why the question is important.

- Use relevant quotes and make sure they are 100% accurate (use copy/paste) and give the source. E.g. if the question has to do with something I've written, link and quote it.

- Keep it short. If some detailed information is important for reference, put it in a footnote after the question.

- If you refer to something, and it's important to your question, then provide a link. For books you generally want to give the Amazon link. If it's long, say which section is relevant and explain what information the reference has and how it relates to the question.

- Sending money, even just $5, sets your question apart from others.

- I strongly prefer ebooks over paper. They don't have page numbers and do allow searching for quotes. And if you really want me to look at a book and can't find a free link, then buy me the ebook. But it's usually better to just quote a lot instead.

- If your question isn't answered, look at it from another angle or make some progress on it, then ask another question. Having a question unanswered is no big deal. It's not a negative response or a rebuke. No answer is neutral. If it's important, just reread this guide and try again after a few days.

- If you have followup questions or arguments that depend on my answer to the question, especially criticism of my ideas, let me know.

- If you think I need to address this question for Paths Forward reasons, explain that.

- If you want me personally to answer, say why. Otherwise write your question in a generic way that other people could answer, too.

- If you think I'll get value from the question or a followup, tell me what's in it for me.

- Don't be or act helpless or needy, don't act like you deserve free answers, and don't rush and write carelessly.

If this sounds like too much effort to you, then understand that answering your questions is not my problem. But note that you will benefit from these steps too because they'll guide you to do better thinking. They'll help you understand your problem better, make some problem solving progress, and sometimes answer your own question.

My Paths Forward Policy

If you think I'm mistaken or ignorant about something important, I want to hear it. I am open to public comments and criticism. See Paths Forward for an explanation of my methodology for not blocking error correction (always having some Path Forward so that if I'm mistaken, and someone knows it, and they're willing to tell me, then I can be told and I won't ignore it).

I do not reply to everything addressed to me, at all venues. I do reply to a fair amount, but I don't have time to answer everything. However, I will guarantee you some attention if you follow a method of getting my attention which anyone can follow with predictable success. Here's what you do:

Post your issue to my Critical Fallibilism Forum.

If you don't receive a reply from anyone within a few days, post a self-reply with some followup points. Try again. If the first post didn't have them, follow up with a brief statement of why this is important and a brief summary (one paragraph max, each). Also make sure you're providing a clear question or call to action. What do you want to happen next? What sort of response do you want? Mention you want a Path Forward from me.

If you still don't receive a reply within a few days, write a self-reply asking why you didn't receive a reply, and include a brief statement of why replying to you matters and what you're looking for.

If you still don't receive a reply within a few days, email me personally ([email protected]) and ask for an answer and say that you've read Paths Forward. Link the CF Forum topic.

Summary: Post to CF. Follow up on why it matters and what reply you want. Follow up asking why no one is answering. Follow up by emailing me. You will get an answer by the end of this process.

Notes

You're welcome to try contacting me in other ways, and that often works, but no promises.

I don't answer everything the first time, but if you are persistent as stated above, then I can guarantee you an answer.

The reasons I want you to post on my public forum are that I want other forum readers to benefit from my answer, I want my answer to have a public permalink so I can refer other people to it in the future, and I want other people to be able to answer you (instead of me).

If you receive an answer from another person, and you think it's inadequate and really want an answer from me personally, you can continue with the steps outlined above and explain this (say why the answers from the other people are inadequate and why you want my personal attention).

I (or someone else) commonly will answer a point before reaching step 4. Often at step 1. (I'm most responsive on the CF forum, so just posting there is frequently enough to get a reply.)

Like many busy people, I am less inclined to answer if I think something is low quality. I certainly don't want to reply to every low quality thing addressed to me. However, if you follow the steps then you'll get a reply from someone, including from me if necessary. (Often other people are fully capable of answering issues, especially the comments I consider lower quality, so I don't always want to do it personally if someone else will do it.)

If you don't want your content to be exclusive to my forum, that's fine. You're welcome to put it on your own website and post a link or copy/paste.

If you want me to address something which costs money, offer me a free copy somewhere within the first 3 steps. If you won't do that, say why.

If I still don't answer after step 4, your personal email went in my spam folder. I don't think this is a common problem, but if it happens feel free to post to CF again and bring it up and I'll see it or someone else will who can contact me. Or it'd be fine to post 10 blog comments in a row or tweet me or something until I notice. Say that you did the 4 Paths Forward steps and I didn't reply, so maybe the email went in spam, and identify the CF posts in question so I can find them. Or you can email Justin or Alan and they'll get my attention. I mention this because spam filtering is a conceivable problem that could get in the way of Paths Forward, and I don't want that to happen. Email is not 100% reliable for contacting me, but it's pretty good and there are solutions if it fails.

Alternatives

What if you don't want to be so demanding and challenging as to ask for a Path Forward from Elliot/CR/CF? Maybe you expect you're wrong (rather than offering a correction), but you're still interested in pursuing the issue and learning something and getting it resolved? Perhaps you want some Path Forward for yourself to make progress?

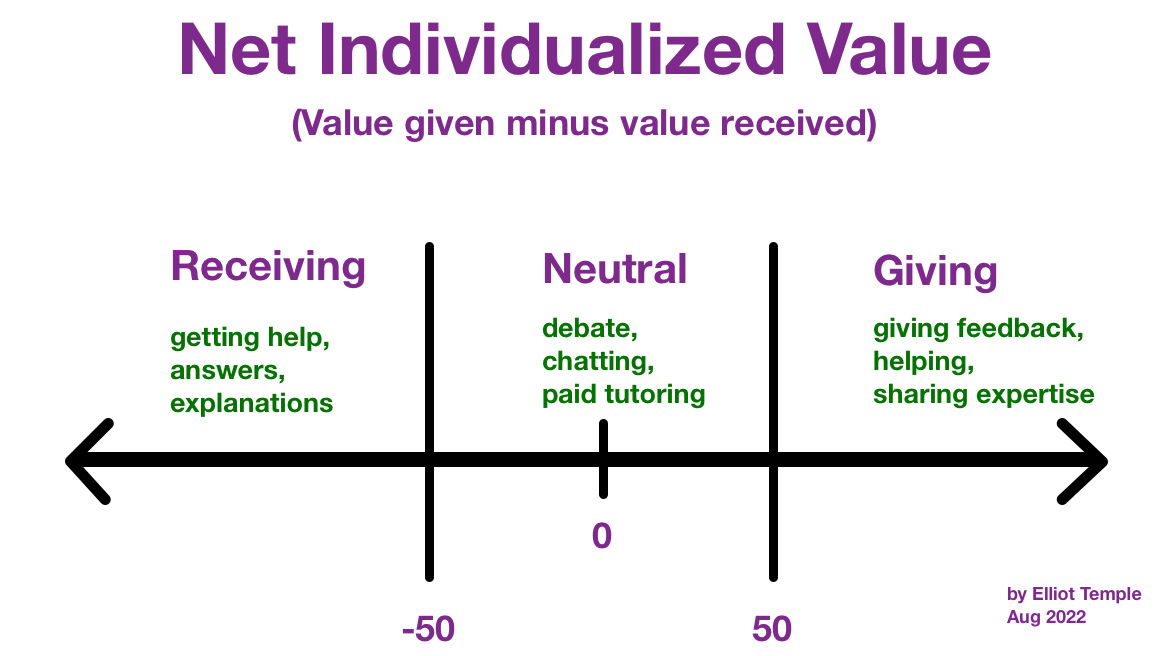

Follow up on your own posts with new questions, new explanations of the issues and their importance, new angles and perspectives. Rewrite what you're saying a different way. And report what you've done to make progress, what effort you've put in (and what the result was), what you're planning to do, and if you're running out of ideas and if you'd like help with something. Keep at it over time. Be persistent, honest and curious and CF people will want to help. And make it easy for them: take short advice/comments/suggestions and then do a bunch more on your own initiative (and share this so they see giving you help was worthwhile), rather than expecting them to guide you step by step. Put effort into your learning as independently as you can, e.g. by taking book and link suggestions and doing series of blog posts about them as you read. Be a pleasure to help and offer more value than you ask for. (If you don't know how to offer value, but want to, ask.)

Update My Paths Forward Policy is a now a backup for my debate policy. The debate policy should handle most issues. Use it first. If something goes wrong with that, the Paths Forward Policy is still available.

Pre-Scripted Discussions

People in conversations usually just say their own (largely pre-determined) stuff, following their own script, because that’s all they know how to say.

They know something, and they are proud to know anything at all, and they go into the discussion planning to talk about that knowledge they do have, and they try to stick to that.

This is why they are so non-responsive when I say things that require off-script responses. They don’t know how to think on their feet and actually address a question. They can basically only answer a question if they already read/heard what to think about it in advance.

Some things this comes up with:

- Meta discussion (e.g. any kind of proposal about how to organize the discussion, like to switch forums, use quotes, or go slower with smaller steps).

- Asking them to engage with critics or rival ideas instead of just present their positive case.

- Any questions they didn’t expect or which seem a bit off topic to them. it doesn’t matter if you have a reason for asking and it’s actually relevant, they don’t know how to answer because it doesn’t fit their script.

- Any criticism that doesn't fit the script, e.g. about their writing being too unclear and failing to communicate. Dealing with misunderstandings isn't part of their script or pre-knowledge.

- The people who seem to be talking to themselves or doing a monologue more than they are having an interactive discussion.

This is unnatural and unintuitive to me because I learn during discussions.

Question-Ignoring Discussion Pattern

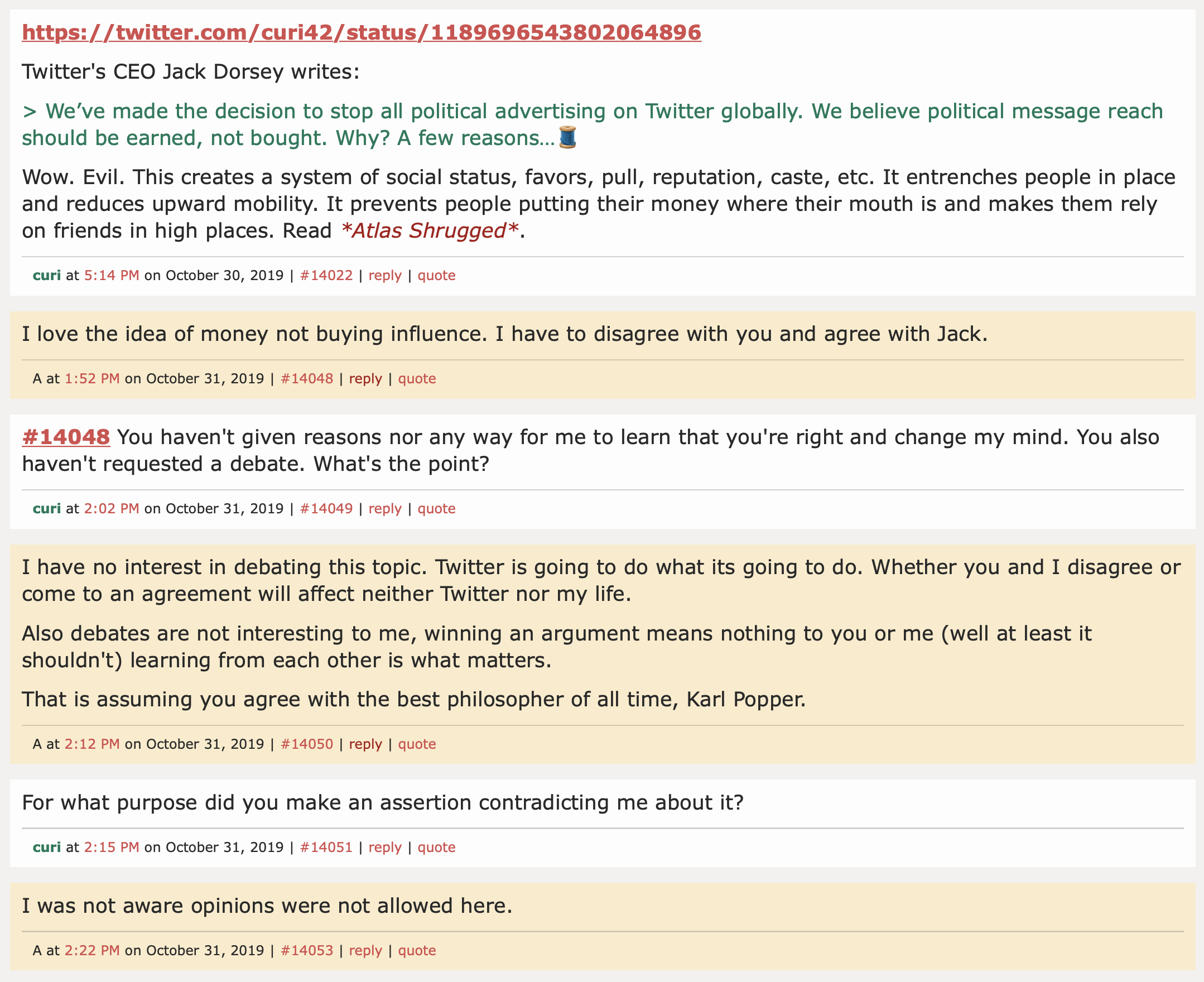

There's a common discussion pattern I've been trying to identify and understand. Example:

Me: What do you think about X?

Them: [silence]

Me: Why didn't you discuss X?

Them: [Starts saying their opinion about X.]

It happens with all kinds of meta discussion, not just asking why they didn't discuss. If you talk about how they were discussing badly, they often ignore you to discuss more. If you ask why they think the topic is unimportant (or whether they think it's important or not, and why), they often ignore that and start discussing it more.

The pattern seems to be they avoid bigger questions and bigger issues, like why they do things. They respond about smaller, more limited issues.

The major indicator of the pattern is they don't directly reply to the last thing you said. You just asked them a question and they start saying something else that is not an answer to the question. That's what stood out to me. They often seem to go back one step. We were talking about X. Then something went wrong, or they stopped talking, or a tangent came up. Then I ask a question about the new issue (the problem, the silence, or the tangent). Then they ignore the question but go back to the previous thing (stop being silent, drop the tangent). If the new issue was a problem, they often silently take one step to try to solve it – they will make a change to try to address the problem, but won't say that they did it, or discuss whether it'll work, they just do it. Often the supposedly problem-solving change is either counter-productive or irrelevant, and it's a burden for them, and they blame me for it (they think of themselves as doing it for me, because I wanted it). But all I'd said is what the problem is, not what I would regard as a solution or what I wanted – they just assumed that while refusing to talk about it.

The discussion issue is partly because people reinterpret questions as demands or assertions. They hear "Why didn't you discuss X?" as meaning "You should discuss X". They hear, "Why are you uninterested in X?" as meaning "X is interesting". They hear, "Do you want to discuss more, or not? You're sending mixed signals." as meaning "I demand you discuss more." They hear "Would it be OK with you if I shared more ideas about X?" as "Let's discuss X more."

I've been trying to understand this pattern and why people do it. I think it's related to people avoiding meta discussion, which I also don't understand very well. What is it about meta discussion that they don't like? My best guess is basically that they avoid talking about more important things in favor of less important ones, which fits their overall life pattern of not having productive discussions and learning philosophy.

I think it's kind of like getting a chore done by procrastinating on an even more unwanted task. They will have regular discussion to avoid discussion that involves "Why?" questions or other important things they find hard. They would feel bad about ignoring something like, "Why don't you want to discuss X? Do you have a reason X is unimportant?" They wouldn't feel justified in ignoring that and still believing themselves to be a rational person who discusses ideas. But if they start discussing X more (breaking their silence, doing one unstated action to try to solve the problem that was disrupting discussion, or dropping a tangent) then they feel legitimized to ignore the question.

One of the straightforward reasons I dislike it is because I don't want to ignore major signs they don't want to talk about X. I don't want to talk about X with a person who doesn't want to discuss X. I don't want to discuss with someone who isn't interested. I don't want to ignore problems like that and go back to the original discussion. Plus, the problems typically reoccur quickly so the discussion doesn't work out.

In general, problems are inevitable and no discussion can work out well, in the long run, without problem solving effort by the participants. But the pattern is people ignore things I say related to problem solving and just go back to the discussion.

Discussion Structure

Dagny wrote (edited slightly with permission):

I think I made a mistake in the discussion by talking about more than one thing at once. The problem with saying multiple things is he kept picking some to ignore, even when I asked him repeatedly to address them. See this comment and several comments near it, prior, where I keep asking him to address the same issue. but he wouldn't without the ultimatum that i stop replying. maybe he still won't.

if i never said more than one thing at once, it wouldn't get out of hand like this in the first place. i think.

I replied: I think the structure of conversations is a bigger contributor to the outcome than the content quality is. Maybe a lot bigger.

I followed up with many thoughts about discussion structure, spread over several posts. Here they are:

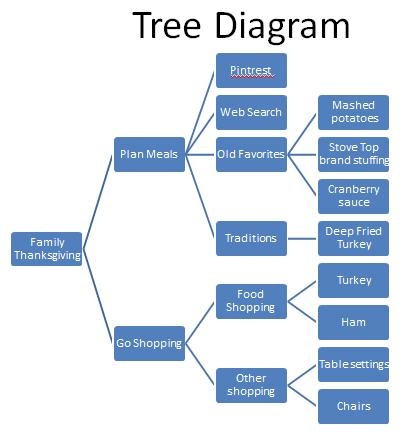

In other words, improving the conversation structure would have helped with the outcome more than improving the quality of the points you made, explanations you gave, questions you asked, etc. Improving your writing quality or having better arguments doesn't matter all that much compared to structural issues like what your goals are, what his goals are, whether you mutually try to engage in cooperative problem solving as issues come up, who follows whose lead or is there a struggle for control, what methodological rules determine which things are ignorable and which are replied to, and what are the rules for introducing new topics, dropping topics, modifying topics?

it's really hard to control discussion structure. people don't wanna talk about it and don't want you to be in control. they don't wanna just answer your questions, follow your lead, let you control discussion flow. they fight over that. they connect control over the discussion structure with being the authority – like teachers control discussions and students don't.

people often get really hostile, really fast, when it comes to structure stuff. they say you're dodging the issue. and they never have a thought-out discussion methodology to talk about, they have nothing to say. when it comes to the primary topic, they at least have fake or dumb stuff to say, they have some sorta plan or strategy or ideas (or they wouldn't be talking about). but with stuff about how to discuss, they can't discuss it, and don't want to – it leads so much more quickly and effectively to outing them as intellectual frauds. (doesn't matter if that's your intent. they are outed because you're discussing rationality more directly and they have nothing to say and won't do any of the good ideas and don't know how to do the good ideas and can't oppose them either).

sometimes people are OK with discussion methodology stuff like Paths Forward when it's just sounds-good vague general stuff, but the moment you apply it to them they feel controlled. they feel like you are telling them what to do. they feel pressured, like they have to discuss the rational way. so they rebel. even just direct questions are too controlling and higher social status, and people rebel.

some types of discussion structure. these aren’t about controlling the discussion, they are just different ways it can be organized. some are compatible with each other and some aren’t (you can have multiple from the list, but some exclude each other):

- asking and answering direct questions

- addressing unstated, generic questions like “thoughts on what i just said?”

- one person questioning the other who answers vs. both people asking and answering questions vs. some ppl ignoring questions

- arguing points back and forth

- saying further thoughts related to what last person said (relevance levels vary, can be like really talking past each other and staying positive, or can be actual discussion)

- pursuing a goal stated by one person

- pursuing a goal stated by two people and mutually agreed on

- pursuing different and unstated goals

- 3+ person discussion

- using quotes of the other discussion participants or not

- using cites/links to stuff outside the discussion or not

- long messages, short messages, or major variance in message length

- talking about one thing at a time

- trying to resolve issues before moving on vs. just rushing ahead into new territory while there are lots of outstanding unresolved points

- step by step vs. chaotic

- people keeping track of the outline or just running down rabbit holes

i’ve been noticing structure problems in discussions more in the last maybe 5 years. Paths Forward and Overreaching address them. lots of my discussions are very short b/c we get an impasse immediately b/c i try to structure the discussion and they resist.

like i ask them how they will be corrected if they’re wrong (what structural mechanisms of discussion do they use to allow error correction) and that ends the discussion.

or i ask like “if i persuade you of X, will you appreciate it and thank me?” before i argue X. i try to establish the meaning X will have in advance. why bother winning point X if they will just deny it means anything once you get there? a better way to structure discussion is to establish some stakes around X in advance, before it’s determined who is right about X.

i ask things like if they want to discuss to a conclusion, or what their goal is, and they won’t answer and it ends things fast

i ask why they’re here. or i ask if they think they know a lot or if they are trying to learn.

ppl hate all those questions so much. it really triggers the fuck out of them

they just wanna argue the topic – abortion or induction or whatever

asking if they are willing to answer questions or go step by step also pisses ppl off

asking if they will use quotes or bottom post. asking if they will switch forums. ppl very rarely venue switch. it’s really rare they will move from twitter to email, or from email to blog comments, or from blog comments to FI, etc

even asking if they want to lead the discussion and have a plan doesn’t work. it’s not just about me controlling the discussion. if i offer them control – with the caveat that they answer some basic questions about how they will use it and present some kinda halfway reasonable plan – they hate that too. cuz they don’t know how to manage the discussion and don’t want the responsibility or to be questioned about their skill or knowledge of how to do it.

structure/rules/organization for discussion suppresses ppl’s bullshit. it gives them less leeway to evade or rationalize. it makes discussion outcomes clearer. that’s why it’s so important, and so resisted.

the structure or organization of a discussion includes the rules of the game, like whether people should reply more tomorrow or whether it's just a single day affair. the rules for what people consider reasonable ways of ending a discussion are a big deal. is "i went to sleep and then chose not to think about it the next day, or the next, or the next..." a reasonable ending? should people actually make an effort to avoid that ending, e.g. by using software reminders?

should people take notes on the discussion so they remember earlier parts better? should they quote from old parts? should they review/reread old parts?

a common view of discussion is: we debate issue X. i'm on side Y, you're on side Z. and ppl only say stuff for their side. they only try to think about things in a one-sided, biased way. they fudge and round everything in their favor. e.g. if the number is 15, they will say "like 10ish" or "barely over a dozen" if a smaller number helps their side. and the other guy will call it "around 20" or "nearly 18".

a big part of structure is: do sub-plots resolve? say there's 3 things. and you are trying to do one at a time, so you pick one of the 3 and talk about that. can you expect to finish it and get back to the other 2 things, or not? is the discussion branching to new topics faster than topics are being resolved? are topics being resolved at a rate that's significantly different from zero, or is approximately nothing being resolved?

another part of structure is how references/cites/links are used. are ideas repeated or are pointers to ideas used? and do people try to make stuff that is suitable for reuse later (good enough quality, general purpose enough) or not? (a term similar to suitable for reuse is "canonical").

I already knew that structural knowledge is the majority of knowledge. Like a large software project typically has much more knowledge in the organization than the “payload” (aka denotation aka direct purpose). “refactoring" refers to changing only the structure while keeping the function/content/payload/purpose/denotation the same. refactoring is common and widely known to be important. it’s an easy way for people familiar with the field to see that significant effort goes into software knowledge structure cuz that is effort that’s pretty much only going toward structure. software design ideas like DRY and YAGNI are more about structure than content. how changeable software is is a matter of structure ... and most big software projects have a lot more effort put into changes (like bug fixes, maintenance and new features) than into initial development. so initial development should focus more effort on a good structure (to make changes easier) than on the direct content.

it does vary by software type. games are a big exception. most games they have most of their sales near release. most games aren’t updated or changed much after release. games still need pretty good structure though or it’d be too hard to fix enough the bugs during initial development to get it shippable. and they never plan the whole game from the start, they make lots of changes during development (like they try playing it and think it’s not fun enough, or find a particular part works badly, and change stuff to make it better), so structure matters. wherever you have change (including error correction), structure is a big deal. (and there’s plenty of error correction needed in all types of software dev that make substantial stuff. you can get away with very little when you write one line of low-risk code directly into a test-environment console and aren’t even going to reuse it.)

it makes sense that structure related knowledge is the majority of the issue for discussion. i figured that was true in general but hadn’t applied it enough. knowledge structure is hard to talk about b/c i don’t really have people who are competent to discuss it with me. it’s less developed and talked through than some other stuff like Paths Forward or Overreaching. and it’s less clear in my mind than YESNO.

so to make this clearer:

structure is what determines changeability. various types of change are high value in general, including especially error correction. wherever you see change, especially error correction, it will fail without structural knowledge. if it’s working ok, there’s lots of structural knowledge.

it’s like how the capacity to make progress – like being good at learning – is more important than how much you know how or how good something is now. like how a government that can correct mistakes without violence is better than one with fewer mistakes today. (in other words, the structure mistake of needing violence to correct some categories of mistake is a worse mistake than the non-structure mistake of taxing cigarettes and gas. the gas tax doesn’t make it harder to make changes and correct errors, so it’s less bad of a mistake in the long run.)

Intro to knowledge structure (2010):

http://fallibleideas.com/knowledge-structure

Original posts after DD told me about it (2003)

http://curi.us/988-structural-epistemology-introduction-part-1

http://curi.us/991-structural-epistemology-introduction-part-2

The core idea of knowledge structure is that you can do the same task/function/content in different ways. You may think it doesn’t matter as long as the result is (approximately) the same, but the structure matters hugely if you try to change it so it can do something else.

“It” can be software, an object like a hammer, ideas, or processes (like the processes factory workers use). Different software designs are easier to add features to than others. You can imagine some hammer designs being easier to convert into a shovel than others. Some ideas are easier to change than others. Or imagine two essays arguing equally effectively for the same claim, and your task is to edit them to argue for a different conclusion – the ease of that depends on the internal design of the essays. And for processes, for example the more the factory workers have each memorized a single task, and don’t understand anything, the more difficult a lot of changes will be (but not all – you could convert the factory to build something else if you came up with a way to build it with simple, memorizable steps). Also note the ease of change often depends on what you want to change to. Each design makes some sets of potential changes harder or easier.

Back to the ongoing discussion (which FYI is exploratory rather than having a clear conclusion):

“structure” is the word DD used. Is is the right word to use all the time?

Candidate words:

- structure (DD’s word)

- design

- organization

- internal design

- internal organization

- form

- layout

- style

- plan

- outline

I think “design” and “organization” are good words. “Form” can be good contextually.

What about words for the non-structure part?

- denotation (DD’s word)

- content

- function

- payload

- direct purpose

- level one purpose

- task

- main point

- subject matter

The lists help clarify the meaning – all the words together are clearer than any particular one.

What does a good design offer besides being easier to change?

Flexibility: solves a wider range of relevant problems (without needing to change it, or with a smaller/easier change). E.g. a car that can drive in the snow or on dry roads, rather than just one or the other.

Easier to understand. Like computer code that’s easier to read due to being organized well.

Made up of somewhat independent parts (components) which you can separate and use individually (or in smaller groups than the original total thing). The parts being smaller and more independent has advantages but also often involves some downsides (like you need more connecting “glue” parts and the attachment of components is less solid).

Easier to reuse for another purpose. (This is related to changeability and to components. Some components can be reused without reusing others.)

Internal reuse (references, pointers, links) rather than new copies. (This is usually but not always better. In general, it means the knowledge is present that two instances are actually the same thing instead of separate. It means there’s knowledge of internal groupings.)

Good structures are set up to do work (in a certain somewhat generic way), and can be told what type of work, what details. Bad structures fail to differentiate what is parochial details and what is general purpose.

The more you treat something as a black box (never take it apart, never worry about the details of how it works, never repair it, just use it for its intended purpose), the less structure matters.

In general, the line between function and design is approximate. What about the time it takes to work, or the energy use, or the amount of waste heat? What are those? You can do the same task (same function) in different ways, which is the core idea of different structures, and get different results for time, energy and heat use. They could be considered to be related to design efficiency. But they could also be seen as part of the task: having to wait too long, or use too much energy, could defeat the purpose of the task. There are functionality requirements in these areas or else it would be considered not to work. People don’t want a car that overheats – that would fail to address the primary problem of getting them from place to place. It affects whether they arrive at their destination at all, not just how the car is organized.

(This reminds me of computer security. Sometimes you can beat security mechanisms by looking at timing. Like imagine a password checking function that checks each letter of the password one by one and stops and rejects the password if a letter is wrong. That will run more slowly based on getting more letters correct at the start. So you can guess the password one letter at a time and find out when you have it right, rather than needing to guess the whole thing at once. This makes it much easier to figure out the password. Measuring power usage or waste heat could work too if you measured precisely enough or the difference in what the computer does varied a large enough amount internally. And note it’s actually really hard to make the computer take exactly the same amount of time, and use exactly the same amount of power, in different cases that have the same output like “bad password”.)

Form and function are related. Sometimes it’s useful to mentally separate them but sometimes it’s not helpful. When you refactor computer code, that’s about as close to purely changing the form as it gets. The point of refactoring is to reorganize things while making sure it still does the same thing as before. But refactoring sometimes makes code run faster, and sometimes that’s a big deal to functionality – e.g. it could increase the frame rate of a game from non-playable to playable.

Some designs actively resist change. E.g. imagine something with an internal robot that goes around repairing any damage (and its programmed to see any deviation or difference as damage – it tries to reverse all change). The human body is kind of like this. It has white blood cells and many other internal repair/defense mechanisms that (imperfectly) prevent various kinds of changes and repair various damage. And a metal hammer resists being changed into a screwdriver; you’d need some powerful tools to reshape it.

The core idea of knowledge structure is that you can do the same task/function/content in different ways. You may think it doesn’t matter as long as the result is (approximately) the same, but the structure matters hugely if you try to change it so it can do something else.

Sometimes programmers make a complicated design in anticipation of possible future changes that never happen (instead it's either no changes, other changes, or just replaced entirely without any reuse).

It's hard to predict in advance which changes will be useful to make. And designs aren't just "better at any and all changes" vs. "worse at any and all changes". Different designs make different categories of changes harder or easier.

So how do you know which structure is good? Rules of thumb from past work, by many people, doing similar kinds of things? Is the software problem – which is well known – just some bad rules of thumb (that have already been identified as bad by the better programmers)?

- Made up of somewhat independent parts (components) which you can separate and use individually (or in smaller groups than the original total thing). The parts being smaller and more independent has advantages but also often involves some downsides (like you need more connecting “glue” parts and the attachment of components is less solid).

this is related to the desire for FI emails to be self-contained (have some independence/autonomy). this isn't threatened by links/cites cuz those are a loose coupling, a loose way to connect to something else.

- Easier to reuse for another purpose. (This is related to changeability and to components. Some components can be reused without reusing others.)

but, as above, there are different ways to reuse something and you don't just optimize all of them at once. you need some way to judge what types of reuse are valuable, which partly seems to depend on having partial foresight about the future.

The more you treat something as a black box (never take it apart, never worry about the details of how it works, never repair it, just use it for its intended purpose), the less structure matters.

sometimes the customer treats something as a black box, but the design still matters a lot for:

- warranty repairs (made by the company, not by the customer)

- creating the next generation production

- fixing problems during development of the thing

- the ability to pivot into other product lines (additionally, or instead of the current one) and reuse some stuff (be it manufacturing processes, components from this product, whatever)

- if it's made out of components which can be produced independently and are useful in many products, then you have the option to buy these "commodity parts" instead of making your own, or you can sell your surplus parts (e.g. if your factory manager finds a way to be more efficient at making a particular part, then you can either just not produce your new max capacity, or you could sell them if they are useful components to others. or you could use the extra parts in a new product. the point was you can end up with extra capacity to make a part even if you didn't initially design your factory that way.)

In general, the line between function and design is approximate.

like the line between object-discussion and meta-discussion is approximate.

as discussion structure is crucial (whether you talk about it or not), most stuff has more meta-knowledge than object-knowledge. here's an example:

you want to run a small script on your web server. do you just write it and upload? or do you hook it into existing reusable infrastructure to get automatic error emails, process monitoring that'll restart the script if it's not running, automatic deploys of updates, etc?

you hook it into the infrastructure. and that infrastructure has more knowledge in it than the script.

when proceeding wisely, it's rare to create a ton of topic-specific knowledge without the project also using general purpose infrastructure stuff.

Form and function are related.

A lot of the difference between a smartphone and a computer is the shape/size/weight. That makes them fit different use cases. An iPhone and iPad are even more similar, besides size, and it affects what they're used for significantly. And you couldn't just put them in an arbitrary form factor and get the same practical functionality from them.

Discussion and meta-discussion are related too. No one ever entirely skips/omits meta discussion issues. People consider things like: what statements would the other guy consent to hear and what would be unwanted? People have an understanding of that and then don't send porn pics in the middle of a discussion about astronomy. You might complain "but that would be off-topic". But understanding what the topic is, and what would be on-topic or off-topic is knowledge about the discussion, rather than directly being part of the topical discussion. "porn is off topic" is not a statement about astronomy – it is itself meta discussion which is arguably off topic. you need some knowledge about the discussion in order to deal with the discussion reasonably well.

Some designs actively resist change.

memes resist change too. rational and static memes both resist change, but in different ways. one resists change without reasons/arguments, the other resists almost all change.

Discussion and meta-discussion are related too.

Example:

House of Sunny podcast. This episode was recommended for Trump and Putin info at http://curi.us/2041-discussion#c10336

- starts with music

- then radio announcer voice

- voice says various introductory stuff. it’s not just “This is the house of Sunny podcast.” It says some fluff with social connotations about the show style, and gives a quick bio of the host (“comedian and YouTuber”)

- frames the purpose of the upcoming discussion: “Wanna know what Sunny and her friends are thinking about this week?”

- tries to establish Sunny as a high status person who is worthy of an introduction that repeats her name like 4 times (as if her name matters)

- applause track

- Sunny introduces herself, repeating lots of what the intro just said

- Sunny uses a socially popular speaking voice with connotations of: young, pretty, white, adult, female. Hearing how she speaks, for a few seconds, is part of the introduction. It’s information, and that information is not about Trump and Putin.

- actual content starts 37 seconds in

This is all meta so far. It’s not the information the show is about (Trump and Putin politics discussion). It’s about the show. It’s telling you what kind of show it’s going to be, and who the host is. That’s just like discussing what kind of discussion you will have and the background of a participant.

The intro also links the show to a reusable show structure that most listeners are familiar with. People now know what type of show it is, and what to expect. I didn’t listen to much of the episode, but for the next few minutes the show does live up to genre expectations.

I consider the intro long, heavy-handed and blatant. But most people are slower and blinder, so maybe it’s OK. I dislike most show intros. Offhand I only remember liking one on YouTube – and he stopped because more fans disliked it than liked it. It’s 15 seconds and I didn’t think it had good info.

KINGmykl intro: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TrN5Spr1Q4A

One thing I notice, compared to the Sunny intro, is it doesn’t pretend to have good info. It doesn’t introduce mykl, the show, or the video. (He introduces his videos non-generically after the intro. He routinely asks how your day is going, says his is going great, and quickly outlines the main things that will be in the video cuz there’s frequently multiple separate topics in one video. Telling you the outline of the upcoming discussion is an example of useful meta discussion.)

The Sunny intro is so utterly generic I found it boring the first time I heard it. I’ve heard approximately the same thing before from other shows! I saw the mykl intro dozens of times, and sure I skipped it sometimes but not every time, and I remember it positively. It’s more unique, and I don’t understand it as well (it has some meaning, but the meaning is less clear than in the Sunny intro.) I also found the Sunny intro to scream “me too, I’m trying hard to fit in and do this how you’re supposed to” and the mykl intro doesn’t have that vibe to me. (I could pretty easily be wrong though, maybe they both have a fake, tryhard social climber vibe in different ways. Maybe i’m just not familiar enough with other videos similar to mykl’s and that’s why I don’t notice. I’ve watched lots of gaming video content, but a lot of that was on Twitch so it didn’t have a YouTube intro. I have seen plenty of super bland gamer intros. mykl used to script his videos and he recently did a review of an old video. He pointed out ways he was trying to present himself as knowing what he’s talking about, and found it cringey now. He mentioned he stopped scripting videos a while ago.)

Example 2: Chef Heidi Teaches Hoonmaru to Cook Korean Short Rib

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EwosbeZSSvY

- music

- philly fusion overwatch league team intro (FYI hoonmaru is a fusion twitch streamer, not a pro player)

- slow mo arrival

- hoonmaru introducing what’s going on (i think he lied when he said that he thought of this activity)

- hoonmaru talking about his lack of cooking experience

- hoonmaru says he’ll answer fan questions while cooking

- says “let’s get started”

- music and scene change

- starts introducing the new seen by showing you visuals of hoonmaru in an apron

- now we see Chef Heidi and she does intro stuff, asks if he’s ready to cook, then says what they’ll be doing.

The last three are things after “let’s get started” that still aren’t cooking. Cooking finally starts at 48s in. But after a couple seconds of cooking visuals, hoonmaru answers an offtopic fan question before finally getting some cooking instruction. Then a few seconds later hoonmaru is neglecting his cooking, and Heidi fixes it while he answers more questions. Then hoonmaru says he thinks the food looks great so far but that he didn’t do much. This is not a real cooking lesson, it’s just showing off Heidi’s cooking for the team and entertaining hoonmaru fans with his answers to questions that aren’t really related to overwatch skill.

Tons of effort goes into setting up the video. It’s under 6 minutes and spent 13.5% on the intro. I skipped ahead and they also spend 16 seconds (4.5%) on the ending, for a total of 18% on intro and ending. And there’s also structural stuff in the middle, like saying now they will go cook the veggies while the meat is cooking – that isn’t cooking itself, it’s structuring the video and activities into defined parts to help people understand the content. And they asked hoonmaru what he thought of the meat on the grill (looks good... what a generic question and answer) which was ending content for that section of the video.

off topic, Heidi blatantly treats hoonmaru like a kid. at 4:45 she’s making a dinner plate combining the foods. then she asks if he will make it, and he takes that as an order (but he hadn’t realized in advance he’d be doing it, he just does whatever he’s told without thinking ahead). and then the part that especially treats him like a kid is she says she’s taking away the plate she made so he can’t copy it, he has to try to get the right answer (her answer) on his own, she’s treating it like a school test. then a little later he’s saying his plating sucks and she says “you did a great job, it’s not quite restaurant”. there’s so much disgusting social from both of them.

Judging Experts by the Objective State of the Debate

Human civilization has more knowledge than any one person. We have a division of intellectual labor. Some people specialize in chemistry, others law, others fashion, others history, others football. A specialist in a type of knowledge is called an “expert” or even an “authority” for his field. The division of intellectual labor has progressed to the point of narrow specialities – e.g. we have experts in ancient Greek history, or WWII history, rather than all of history. There are different kinds of scientists, and then within a kind, e.g. physicist, there are sub-kinds, e.g. astrophysicist.

People accept expert advice from car mechanics, doctors, lawyers, scientists, tech support people, sports coaches and more. You may be able to learn about a few topics, in detail, yourself, but not all the topics that come up in your life. There’s too much to know it all yourself.

If you didn’t use other people’s expert knowledge – if you didn’t participate in the intellectual division of labor – you’d be handicapped, have a limited life and not accomplish much compared to people who do (just the same as a person who doesn’t participate in the economic division of labor cannot produce much compared to people who do participate).

The intellectual division of labor raises problems to be addressed. How do you know which ideas from other people to use? How do you judge an expert’s claim when you don’t know much about the field? How can decide what to think when experts in a field disagree with each other?

One attempted solution is credentials. Some people perform the task of judging experts. But the people saying which experts are good are themselves experts (in the field of judging expertise), so you’re left with the same problem of deciding which experts to listen to. That's just moved the problem: instead of deciding whether to listen to a scientist saying humans evolved, you decide whether to listen to a guy telling you he knows which scientists to listen to. And normally the qualifications of the people giving out credentials in a field are that they are experts in that field (not that they actually have any special expertise at judging experts), so it’s really just “Listen to me about which physicists you should listen to, because I’m a good physicist.”

Another attempted solution is reputation. Some people have a bunch of success in some visible way and then people listen to them more. And reputations can partially carry over to their associates, and to a lesser degree to their associate’s associates.

Another attempted solution – which is how a lot of reputation works – is to judge by popularity. But great ideas usually start out unpopular.

Another way people judge expertise is by charisma, social status, social skill, and stuff like that (including dressing well and speaking in a “smart” sounding way). This is a poor method. It leads to competitions not at field expertise but at expertise in impressing people and presenting as credible to them.

Another way people judge experts is by which ones create material (articles, books, videos, etc.) for a general audience that they like. This isn’t very good at figuring out who is the best at the details of the field because it looks for skills like being able to communicate well about the basics of the field.

I propose a better way to judge experts. This solution is especially meant for intellectuals rather than, e.g., bike repair experts. Experts should provide public information which can be evaluated by lay people. It’s their job to prove their own case if they want to be considered an expert. But how? Specifically by being open to debate. Experts should be open to questions and criticism, in public, and organize the information in a way that people can look it over and see who blocked further progress on resolving the disagreement. The public should favor experts who have addressed all outstanding criticism of their knowledge over experts who have withdrawn from that kind of discussion, ignored criticisms, refused to answer questions, derailed debates, etc. Experts should be judged by the current state of the debate in the field, and should organize that debate so it isn’t a mess with no clear answers.

People who don’t know how to do this aren’t fit to be experts in a fields that deal with controversies (but maybe they can successfully be an expert accountant). If your field has ongoing disagreements and debate, then you need to know how to organize and evaluate disagreements and debate in order to do effective work in your field.

The starting point of clarifying the state of the debate is to invite debate. The people who decline debate are the people blocking resolution of the issues. The people who are unwilling to try to address questions and criticisms should be presumed wrong, even though they might be right about some particular issues, because their methodology – their way of dealing with knowledge – is not oriented towards truth-seeking. People who reject intellectual collaboration, on principle, are limiting their participation in the intellectual division of labor and thereby limiting their effectiveness (just like a business that won’t consider any business deals with other businesses).

A good expert has the general attitude: “If I’m wrong, tell me what I’m wrong about. And I’ve told you what you’re wrong about and I’m still waiting for you to respond.” And he thinks of debate as primarily a matter of writing, over time, not verbal debate in person. So he can write a blog post criticizing something, and that advances the state of the debate, and if it’s not answered then that shows the other guy isn’t debating (or discussing, which should be the same thing). And it shows the other guy also lacks proxies to discuss for him. And lacks sources he could cite that address the issue with no new work. (Or else he has the perfect answer, already written, and just won’t bother to share the link, and none of his fans will share the link either? Not a plausible story.)

Openness to debate is a well known criterion, so many people pretend to meet it. But most don’t pretend in more than a token way. Suppose I wrote a blog post with some questions and criticisms for an expert. You, right now, could predict that most experts would ignore me. For example, Richard Dawkins would ignore me (and that’s not mere speculation, I have actually contacted him and been ignored, even though I’m an expert who has written serious criticism of some of his work). His openness to debate is limited in some ways.

What are the limits on the openness to debate of Dawkins and the large majority of other supposed experts? I could try to analyze and criticize them and talk about some Paths Forward stuff. But there’s a much simpler way for lay people to evaluate the matter. Has Dawkins written down what his limits on debate are, himself? Has he publicly shared a policy stating his openness to debate, including the limits and the reasons for those limits? Has he asked if anyone knows any ways to remove or reduce any of those limits? No he has not. Because he isn’t seriously interested in discussing and getting disagreements resolved.

Many experts were more open to debate when they were younger, and they get disillusioned after many bad, ineffective discussions. They give up and decide talking with people is mostly a waste of time. What they should have done is learned better methods that better conserve their time, get to the point faster, and so on (see Paths Forward for info on how to do that). Organize the debate better instead of giving up on debate (and then dishonestly pretending you’re still open to debate). Learn enough philosophy – methods of dealing with ideas, learning, resolving disagreements between ideas, etc. – to be an effective intellectual. Sure that’s hard (most philosophy is crap) but if you want to be a good intellectual you need to deal with that problem and find or create and then use actual good methods for making intellectual progress (and if you think you have those, write them down and expose those to criticism and debate, and also make them available for others to learn and use if you think they actually work well! As I have done.).

By the way, what if all the experts in a field are bad? What if none of them are really open to debate? Then it’s hard to evaluate, so you should ask a philosopher (general purpose expert) to evaluate the field (and you can judge which philosophers are experts by their openness to debate).

Discussing = Thinking

Discussion is externalized thinking. Thinking is self-discussion.

Not entirely. This mostly applies to the conscious aspects of thinking. It’s thinking that you pay attention to, not autopilot/habits.

Rational critical analysis looks at the content of ideas, not their sources. It doesn’t matter if the source is you or someone else, it’s the same idea either way. The same sort of analysis needs to be done to evaluate two rival ideas regardless of their sources – which means, regardless of whether they come from two different people in a discussion or from one person who is thinking silently.

Discussion lets other people share criticism with you and learn from you. Those are big benefits. They help share good ideas and overcome people’s personal weaknesses. Some of your weaknesses are not shared by some of your discussion partners, and you don’t have some of their weaknesses, so there’s lots of scope to help each other.

Good thinkers can think out loud and can think as part of discussion. They don’t have to think alone first, in advance of discussion. They can do some thinking in real time, and some in fairly near real time (writing a text reply slower than talking out loud as one thinks, but without taking any significant break to think things over).

People who have trouble thinking in discussion also have trouble thinking outside of discussion. But there are some important differences. People who get pressured and socially manipulated a lot can think better alone because those things happen less when there isn’t another person directly involved. But if they were a better thinker they’d deal with that better.

Many people believe they know an idea, they just can’t explain it well. They separate thinking and communication as different skills. But if you can explain the idea to yourself, you can use that same explanation with other people!

People also claim they have arguments that convince themselves but wouldn’t convince you. This is biased. They believe it’s because they have access to information that you don’t, e.g. their own internal feelings or memories. But they can tell you those. You and they should both see the evidence the same way: “Joe reports remembering X.” or “Bob says that he feels Y very strongly and seriously.” The reason they think it’s more convincing for them, than you, is they realize that those kinds of reports are unreliable and you won’t accept it, but they believe those kinds of reports, anyway, when they are the reporter. That’s biased and bad thinking. People should learn to be skeptical of their own beliefs. If they know they have a belief that a reasonable external person would be skeptical of, they should doubt it themselves, too.

People also separate truth-seeking and debating as different skills. They think the better thinker, with the better idea, can lose a debate because he is less good at clever rhetoric. This is reasonably accurate when both thinkers aren’t very good. But great thinkers can handle these issues. A good thinker can point out rhetoric, manipulation, faking, etc. A good thinker will refocus the discussion on key points like what are the criticisms of each idea, and ask the other person to cooperate in joint truth-seeking. The gullible people in the audience may still be fooled, but that should clarify matters enough for the reasonable people to be able to see what’s going on. (Of course errors can always happen. There are no guarantees.)

All this means: learning to discuss is a way of learning to think well. And learning to think well without learning to discuss well is implausible and is a sign of fooling yourself. Because thinking and discussion are linked, and most genuine skill at either one also works for the other.

Errors Merit Post-Mortems

After people make errors, they should do post-mortems. How did that error happen? What caused it? What thinking processes were used and how did they fail? Try to ask “Why?” several times to get to deeper issues than your initial answers.

And then, especially, what other errors would that cause also cause? This gives info about the need to make changes going forward, or not. Is it a one-time error or part of a pattern?

Effective post-mortems are something people generally don’t want to do. What causes errors? Frequently it’s irrationality, including dishonesty.

Lots of things merit post-mortems other than losing a debate. If you have an inconclusive debate, why didn’t you do better? No doubt there were errors in your communication and ideas. If you ask a question, why were you ignorant of the answer? What happened there? Maybe you made a mistake. That should be considered. After you ask a question and get an answer, you should post-mortem whether your understanding is now adequate. People usually don’t discuss thoroughly enough to effectively learn the answers to their questions.

Regarding questions: If you were ignorant of something because you hadn’t yet gotten around to learning about it, and you knew the limits of your knowledge, that can be a quick and easy post-mortem. That’s fine, but you should check if that’s what happened or it’s something else that merits more attention. Another common, quick post-mortem for a question is, “I asked because the other person was unclear, not because of my own ignorance.” But many questions relate to your own confusions and what went wrong should be post-mortemed. And if you hadn’t learned something yet, you should consider if you are organizing your learning priorities in a reasonable way. Why learn this now? Why not earlier or later? Do you have considered reasoning about that?

What if you try to post-mortem something and you don’t know what went wrong? If your post-mortem fails, that is itself something to post-mortem! Consider what you’ve done to learn how to post-mortem effectively in general. Have you studied techniques and practiced them? Did you start with easier cases and succeed many times? Do you have a history of successes and failures which you can compare this current failure to? Do you know what your success rate at post-mortems is in general, on average? And you should consider if you put enough effort into this particular post-mortem or just gave up fast.

You may wonder: We make errors all the time. Should we post-mortem all of them? That sounds like it’d take too much time and effort.

First, you can only post-mortem known errors. You have to find out something is an error. You can’t post-mortem it as an error just because people 500 years from now will know better. This limits the issues to be addressed.

Second, an irrelevant “error” is not an error. Suppose I’m moving to a new home. I’m measuring to see where things will fit. I measure my couch and the measurement is accurate to within a half inch. I measure where I want to put it and find there are 5 inches to spare (if it was really close, I’d re-measure). The fact that my measurement is an eighth of an inch off is not an error. The general principle is that errors are reasons a solution to a problem won’t work. The small measurement “error” doesn’t prevent my from succeeding at the problem I’m working on, so it’s not an error. It would be an error in a different context like doing a science experiment that relies on much more accurate measurements, but I’m not doing that.

Third, yes you should try to post-mortem all your errors that get past the previous two points. If you find this overwhelming, there are two things to do:

- Do easier stuff so you make fewer errors. Get your error rate under control. There’s no benefit to doing stuff that’s full of errors – it won’t work. Correctness works better both for immediate practical benefits (you get more stuff done that is actually good or effective instead of broken) and for learning better so you can do better in the future.

- Learn and write down recurring patterns/themes/concepts and reuse them instead of trying to work out every post-mortem from scratch. If you develop good ideas that can help with multiple post-mortems, that’ll speed it up a ton. Reusing ideas is a major part of Paths Forward and is crucial to all of life.

Discussion Policy: Quotes or You’re Presumed Wrong

Understanding people you agree with is difficult. Understanding people you disagree with is even harder. When you comment on someone’s position – especially to disagree – it helps to use an exact quote and then directly engage with their words. The quote should have a source, too, so that people can check the context and accuracy of the quote.

If you specifically attribute an idea to a person, then you should quote it. If you only paraphrase from memory, you may do it wrong, and there’s no reasonable way to refute your mistake. Without a source, no one can point out your misreadings, nor can they see that you’re right and change their mind. All people can say is “uhh i don’t think i said that, i don’t know what you’re talking about”. That’s not productive.

You should use quotes and sources when the person might not be happy to agree that they said something, or when you’re saying something critical or negative.

If the person said something similar to what you remember, the difference may matter. Let’s see the actual quote. Maybe they were precise with their wording in ways you don’t even think about. Or not. We need the quote in order to analyze and decide.

Also, don’t use controversial examples from past discussions without quotes or references. It’s not much of an example if I can’t look at it! People commonly say things like “Joe was [bad thing] in a discussion 3 months ago” without quotes or details. (Examples of bad things to go in that sentence: mean, rude, dishonest, unreasonable, incorrect, wrong.) Sometimes people don’t even give a paraphrase or summary, they just claim something happened.

Often, people didn’t criticize Joe’s statements at the time they were said. Now they are bringing them up without any details. This avoids analysis, at the time or later, of whether their claim about Joe’s statements is correct or incorrect (that typically seems to be the goal of not using quotes). And it indicates they were holding an unstated grudge, which was hidden from criticism (like correcting a misunderstanding or incorrect logical reasoning). They never gave Joe the opportunity to change his mind, retract his statement, learn from his error, or refute the charges – and yet they remembered it negatively, or else they wouldn’t have brought it up negatively at a later time (especially without a quote, which means they didn’t go look it up to refresh their memory). It’s also especially unfair to expect other people to remember something that you thought was negative but you didn’t complain about at the time – you didn’t draw attention to it, so why would others have picked out that particular thing to remember?

Rational criticism involves explaining why something is a mistake. It has to be possible to learn from the criticism, but Joe won’t learn from being told an unspecified past statement was bad. And it has to be possible to refute the criticism, but there’s no way to give counter-arguments when the details are missing. (All one can do is refute the method of criticism for not using quotes, but that doesn’t actually mean Joe didn’t do the bad thing.)

So, at my forums – and I’d recommend this everywhere – don’t make unsourced accusations.

Update: I think this needs emphasiszing: Quote don't speak for themselves. Give a quote and an argument about that quote.

Three Discussions Approach

This post explains a way of organizing a discussion. It’s meant to be useful in some cases, not all the time. It doesn’t require that the other person know it’s being used. This method can be collaborative, or can be used as tips to guide your own actions.

The problem: people debate endlessly without anything being resolved.

The method: instead of having many debates, focus on reaching clear conclusions about three issues.

How? Ask the other person what they think is important or interesting. Get them to say something serious about an important issue (or link something they already wrote). Then focus on that. Instead of discussing whatever they carelessly say mid-discussion, try to get something more substantial that you can reply to. (People shouldn’t say careless things in discussions that they wouldn’t take responsibility for … that’s irresponsible … but they do.). Then clearly point out mistakes. Do one issue at a time, three times.

Tips: Focus criticism on key topics, not tangents or cherrypicked errors. Preferably, the criticisms to will point out important problems, not “this is incomplete” or “this is sloppy” (that doesn’t mean ignoring incompleteness or sloppiness, it means trying to get them to provide material which is more complete and effortful so that you have something good to respond to). If they can’t produce anything good (in your opinion), get them to say they think something they wrote is good (in their opinion), then point out that it’s incomplete or sloppy. That means they’re a poor judge of quality (which is an important criticism, but that should be your backup plan only if you can’t get them to say anything decent about a primary topic of interest like dinosaurs, history, politics, physics, etc.).

People make lots of excuses about their errors. They don’t want to figure out what caused their error (often a bad thinking method or static meme) and what other errors that cause could cause (often lots) and then fix the underlying problem. Focusing on three high quality critical interactions can reduce excuses. Pick things where they’d have few excuses for being wrong.

Does this method assume you’ll be doing all the criticizing, and unfairly have them stick their neck out while you don’t? That depends. People are welcome to criticize any of my important pieces of writing. Their criticism can be two of the three issues discussed, but shouldn’t be all three. If you want to use this method but have no public writing available for anyone to criticize, that’s a problem.

The second problem: People want answers to their questions, and corrections of their errors, one by one. What they should be doing is learning how to think better for themselves – learn better thinking methods, critical thinking skills and philosophy – so that they can answer more of their own questions and correct more of their own errors. Often, people want to ask a bunch of questions while not saying anything substantial themselves, so they minimize the ideas they expose to criticism.

It’s inefficient to outsource your thinking to me or to another wise person. I don’t have time to answer all your questions. I’ll answer a few if I like them, and to see if you learn much, and because people are interesting, and to interest people in learning my thinking methods (by giving examples of my wisdom). But most of your questions have to be answered by creating your own thinking and research skills, not by using mine. It’s the difference between teaching a man to fish and doing the fishing for him then giving him fish. Answering a question is giving someone a fish.

The solution: People should take an interest in learning to be better thinkers so they make fewer errors and can effectively find or create good ideas. I’ve written (and talked) a lot about how to do this and I’m open to questions about it.

Part of what learning involves is changing one’s mindset. It’s one thing to be a peer or equal, who is contributing about as many fish as he receives. It’s another to be unable to fish. (Or maybe you can only catch small fish, but you ask questions and make claims about big fish and are talking to people who know how to catch big fish. Big fish are complicated ideas.) You need to know which situation you’re in and act accordingly. Should you focus on learning more (to catch up to existing knowledge), or should you pursue your directly projects (with critical discussions and learning being secondary)?

The third problem: People view themselves as peers when they should be learners. And they don’t want to change that. They think they already are educated, good thinkers who can catch their own fish. They view their questions (areas of ignorance) and errors as occasional things, not a major pattern.

The solution: Show them their errors using three clear examples. Show them their ability to deal with ideas is less effective than they think it is, or less effective than it could be if they had the thinking skill that you do. Show them that you catch substantially bigger fish than they can, which is a skill they should learn if they want to successfully contribute anything important to human knowledge (or want to fight with their family less, or otherwise have a better life).

The three discussions method serves multiple purposes. It helps clarify the outcomes of discussions, and it helps limit how many different discussions happen before the patterns in the discussions are addressed, and it helps clarify the relative skill and knowledge of the participants, and it helps show people why they should try to learn to think better (because, three out of three times, they missed errors in their ideas – the type of errors that make the difference between success and failure).

The three discussions method can also show when something else is going on. Maybe the other guy will be right on some of the issues. Maybe there won’t be a pattern of error. Maybe he is wise, too. Maybe he can contribute a fair amount. That’s possible. Maybe you’re roughly equals. Maybe he knows far more than you, and you should be trying to learn from him. The three discussions method helps find out what the situation in a time-and-effort-efficient way.

Link: my discussion forums.

The first comment, below, is a second article on this topic with more info.

FI Posting Tips

Tips for new people using the Fallible Ideas discussion group:

- If you think a criticism is irrelevant, say so and give your reasoning. The person who posted it thought it was relevant. You disagree with him. Discuss your disagreement instead of assuming he’s stupid or acting in bad faith.