This discussion (from Discord) is pretty long. If you want to skip to the best part, click here. That's where I discussed methodology. The earlier conversation involves me trying to ask a bunch of clarifying questions and it being difficult to make progress.

curi:

i think you're underestimating how different people are and how complex FI is.

doubtingthomas:

even for people who are steeped into CR?

curi:

yes

doubtingthomas:

well let's see

curi:

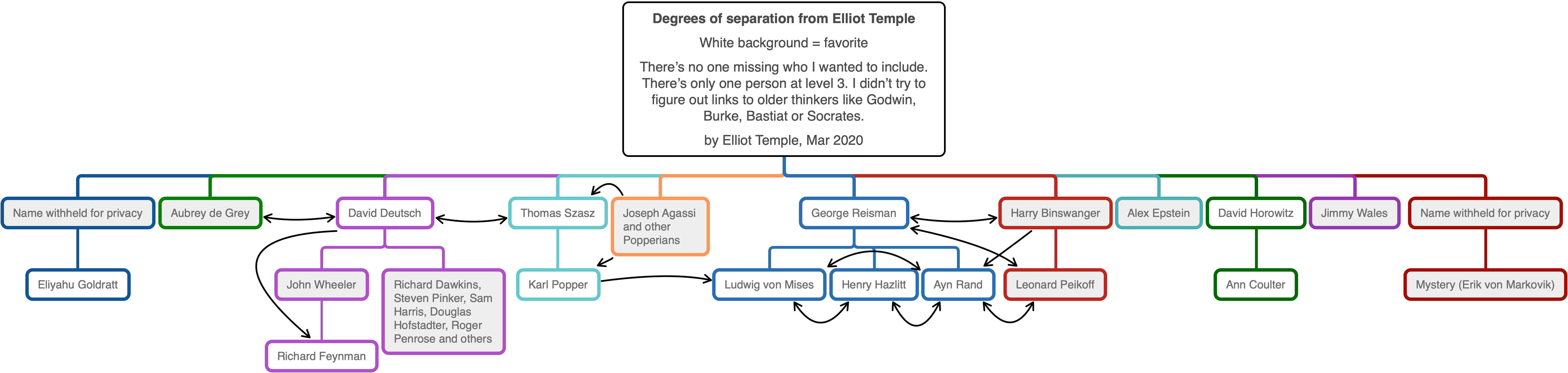

DD and non-DD CR ppl are quite different, and then FI ppl are quite different again

doubtingthomas:

ok

curi:

there are also different subcultures within those groups, e.g. academic and non-academic CR ppl

doubtingthomas:

We're not scoring theories on their reach level or anything in order to decide whether to accept them or not

so what is role of reach in the scientific process?

curi:

reach is a trait of a theory that we can talk about. similar to how blue is a trait of an object we can talk about. it could come up in science sometimes but can also be irrelevant lots of the time.

curi:

reach is useful enough, often enough, in some sort of thinking (can be philosophy or something else, doesn't have to be science) to merit a name.

curi:

it's kinda like the opposite of ad hoc, a concept CR mentions a fair amt

doubtingthomas:

does it give merit to science as a process? does it show that science or rational community is better at thinking than other factions of society?

curi:

not by itself. you could try to incorporate it into an argument to do some of that.

doubtingthomas:

It seems to me like reach is just a failure of science to present a problem where a good explanation becomes refutedd

curi:

i don't really know what you're talking about. i think of reach as basically the number of problems an idea solves. some ideas are really specific to solve one or two problems. some are more general purpose.

doubtingthomas:

if einstein had come just 10 years after newton than should we have marvelled over the genius of newton's theory?

curi:

newton's theory solves a lot of problems. having a better theory doesn't change that.

curi:

i also don't think reach is a good criterion for what to marvel over, at least not alone.

doubtingthomas:

agreed.

curi:

reach is one of many things we tend to like

doubtingthomas:

is there a demarcation which can tell whether it is newton's theory which is solving the problem or einstein's?

doubtingthomas:

sorry

doubtingthomas:

wrong question

curi:

it's not one or the other. they can both solve a problem.

doubtingthomas:

so the idea of paradigm makes sense?

doubtingthomas:

it's not easy to get a hybrid between two theories because a varying a good theory even a bit makes it a bad explanation

doubtingthomas:

you have to kind of jump to another local maxima

curi:

i don't know what you mean by paradigm. but yes BoI talks about difficulty of mixing explanations.

doubtingthomas:

both theories give different solutions to a problem. there is no qualitative difference between those two solutions if they indeed are solutions. the different solutions belong to those theories paradigm

doubtingthomas:

force of gravity being a property of mass belongs to newton's paradigm and bending of spacetime belongs to einstein

doubtingthomas:

paradigm is the supporting ideas of theory which makes a theory itself hard to vary

doubtingthomas:

does that make sense?

curi:

so you're talking about paradigms differently than the Kuhn stuff that KP and DD criticized?

doubtingthomas:

yeah

curi:

problems often have many solutions

doubtingthomas:

paradigm is something like an excompassing area in which a theory can be perfected

curi:

different schools of thought can approach a problem in different ways and both succeed.

doubtingthomas:

newton's theory was the epitome in his own paradigm

doubtingthomas:

it couldn't have been improved in its own paradigm

doubtingthomas:

in that case the idea of tentative progress makes sense. and then you can add reach into scientific process. you can say when science tentatively makes progress it puts forth a theory which has reach

curi:

so re yesno, my essay persuaded you that KP and DD were wrong to talk about ideas like "weak arguments"?

doubtingthomas:

yeah there are no weak arguments. only yes or no. solved or not solved

curi:

i've found most CR ppl are not receptive

doubtingthomas:

do you agree with this?

in that case the idea of tentative progress makes sense. and then you can add reach into scientific process. you can say when science tentatively makes progress it puts forth a theory which has reach

curi:

i'm not very clear on what problem it's trying to solve or what i'd use it for.

doubtingthomas:

Even I'm not sure what problem it solves. I am more interested in the deeper problem it raises: why do solutions fall into these well defined buckets

curi:

what buckets?

doubtingthomas:

paradigms

doubtingthomas:

newton's or eintsein's

curi:

so like why is idea space approximately organized into big semi-autonomous groupings after you take out the crap?

doubtingthomas:

yeah

Qthulhu42:

halfway between two buckets you get obvious contradictions

Qthulhu42:

so that’s an unstable point that must shift either way

curi:

i think that's to be expected because 1) it's sparse 2) problems aren't infinitely demanding. so often a solution can be adjusted a bit and still work b/c there is leeway in the problem.

doubtingthomas:

i've found most CR ppl are not receptive

@curi I think even DD doesn't believe in weak arguments anymore

curi:

he's never retracted it or commented directly on YesNo

curi:

also we have to organize ideas that way – we have to try figure out how to make this work – or we couldn't think about complex things. if ideas aren't semi-autonomous then you can't ever drop some of the complexity out of your mind and set it aside for now to focus on something else. you have to fit everything in your mind at once. you lose out on layers of abstraction like programmers use where you can treat some lower level stuff as a black box and not worry about the implementation details, which is what enables highly complex software.

jordancurve:

like why is idea space approximately organized into big semi-autonomous groupings after you take out the crap?

For the same reason that lifeforms can be organized into kingdoms, phylums, etc. It's because ideas evolve, like DNA. They build on , subtract from, and modify their predecessors.

curi:

disagree. that suggests it's not inherent in the problem space. i think it partly is, both for ideas and organisms.

doubtingthomas:

also we have to organize ideas that way – we have to try figure out how to make this work – or we couldn't think about complex things. if ideas aren't semi-autonomous then you can't ever drop some of the complexity out of your mind and set it aside for now to focus on something else. you have to fit everything in your mind at once. you lose out on layers of abstraction like programmers use where you can treat some lower level stuff as a black box and not worry about the implementation details, which is what enables highly complex software.

@curi now that I think of it the idea space is autonomous. that's what makes science an impersonal thing.

doubtingthomas:

other than that the the claim you made about emergence is very interesting

doubtingthomas:

For the same reason that lifeforms can be organized into kingdoms, phylums, etc. It's because ideas evolve, like DNA. They build on , subtract from, and modify their predecessors.

@jordancurve DNA does not create explanatory knowledge so that analogy doesn't hold

curi:

i don't agree with how DD talks about that.

doubtingthomas:

DNA mutation is undirected and without intention

curi:

at the lowest level, our intelligent thinking process may be that way too. intention and direction may be a higher level thing.

doubtingthomas:

i don't agree with how DD talks about that.

@curi did you say that about DNA and explanatory knowledge or about independent autonomous nature of idea space?

curi:

about DNA and explanatory knowledge

curi:

i find his claims about that not rigorous or explained enough, and generally unnecessary anyway.

jordancurve:

It wasn't meant as an analogy, @doubtingthomas. I believe ideas are literally created by evolution. That's the only one known process to create knowledge.

A big difference between evolution in nature and evolution in a mind is that ideas in a person's mind don't have the strict fitness requirements that an organism has to have in order to reproduce. People can create a sequence of ideas that might not work on their own, but eventually the sequence can arrive at another good idea that does work. That wouldn't work in nature, because every individual creature has to be viable enough to reproduce in order to pass on the knowledge in its DNA to the next generation.

curi:

that's an approximation. more precisely we can switch fitness criteria, including using criteria about being speculation worth pursuing further.

curi:

"this might be on the path to beating a local optimum" is a fitness criterion.

doubtingthomas:

a gene complex or a genome can create multiple different subspecies in the same environment but for a given meme complex there is a perfect newton's theory which cannot be improved further

curi:

you can optimize classical or newtonian physics more. it wasn't an end of progress if right.

doubtingthomas:

there's only certain deep ideas with reach that can open new meme complexes

doubtingthomas:

you can optimize classical or newtonian physics more. it wasn't an end of progress if right.

@curi improving it more would've never taken it into einstein's territory

doubtingthomas:

and a new meme complex envelopes the old one completely. shows why the old one seemed right

curi:

i wasn't saying it would, but "never" is an overstatement.

jordancurve:

Newton's theory has already been improved since Newton: http://www.eftaylor.com/pub/newton_mechanics.html Who's to say it's already reached final perfection?

doubtingthomas:

the few deep ideas with reach which never were killed by the old theory opened the new frontier

doubtingthomas:

when humans evolved they didn't refute bacteria. explanatory knowledge does. difference between genetic vs memetic

jordancurve:

No. Einstein's theory doesn't refute Newton's for many common problems, like understanding what happens when you throw a baseball.

jordancurve:

Ideas and organisms both have niches.

doubtingthomas:

curvature of spacetime tells that unsupported objects and earth move closer to each other

jordancurve:

So? People don't use that knowledge to analyze baseball replays.

jordancurve:

I think they do use Newtonian physics to predict the trajectory of a ball, though.

curi:

i don't think this discussion is organized enough, with clear problem statements and claims, to reach a resolution instead of just exchanging some ideas and dropping it. would suggest discussion trees.

doubtingthomas:

I think they do use Newtonian physics to predict the trajectory of a ball, though.

@jordancurve doesn't matter. they can use einstein's theory to get the same answers

curi:

whether it matters depends what problems you're trying to solve, what the claims under debate are, etc.

curi:

mattering is contextual. it matters to some things and not others. depends what you consider relevant.

doubtingthomas:

all new theories are improvements on the old ones and show why the old ones seem to be true. is there something analogous in genetic evolution?

curi:

that's not a precise statement. you don't mean all new theories. "You will x-fall if you jump out your window" is a new theory which is not an improvement on the old one.

doubtingthomas:

all new explanations which are tentatively accepted as the best known theories now

curi:

accepted by whom? people often accept new explanations which do not explain why an old one seemed to be true.

doubtingthomas:

accepted by science

Freeze:

scientific consensus? that can be wrong often

doubtingthomas:

We cannot read ideas from the book of nature. We create them. Deep good ones with reach are very close to the ones in the idea space and lots of those coalesce around each other because the rivals we guess are close to those.

Freeze:

e.g. climate change

curi:

science is not an actor and doesn't accept things

doubtingthomas:

i wasn't saying it would, but "never" is an overstatement.

@curi agreed. if modification keeps happening then another deep idea will come around which others will coalesce.

curi:

that use of coalesce is underexplained in context.

curi:

these kinds of imprecisions, at an avg rate above one per message, make it hard for the conversation to be effective in the sorts of ways i generally look for in conversations. it may work for your goals, which you haven't stated. trying to communicate to you a bit about some problems as i see them.

doubtingthomas:

my goal is to try to improve my understanding

curi:

i think working on skills to deal with errors like this, so you better understand them and do them way less, would help a lot with improving your understanding.

doubtingthomas:

i think these errors happen because of misunderstanding only. i try to criticise in my mind and when i think it looks presentable for open criticism I put it forward

doubtingthomas:

in that case coalesce is the concept whose understanding I want to improve

curi:

"misunderstanding only" – misunderstanding of what and what is "only" meant to exclude?

doubtingthomas:

"misunderstanding only" – misunderstanding of what and what is "only" meant to exclude?

@curi not misunderstanding. rather a not so good understanding. in this case coalesce. only is meant to exclude everything except coalesce

curi:

we're not on the same page and i'm not following what you're saying.

curi:

i've tried to clarify some points but things i find ambiguous or confusing are being introduced faster than they're being clarified.

doubtingthomas:

I agree

doubtingthomas:

New question. What does the autonomous independent idea space contain? All the computable functions?

curi:

I'm more interested in a strategy for dealing with the problem identified while discussing the prior topic than dropping that problem and expecting it won't happen again on the next topic (or not minding if it happens again).

doubtingthomas:

I think we have reached the 90% of it right now. We should come back to it when I have more clarity. If it happens again it will be with the intention of approaching the problem with a new direction

curi:

90% of what?

doubtingthomas:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nIm_uDV1Ya8

doubtingthomas:

trying to get all the details right to a 100%

curi:

I don't think you got 90% of the details right, if that's what you mean.

doubtingthomas:

Trying a new approach will be better

curi:

I don't think so because I think there are several confusions in " What does the autonomous independent idea space contain? All the computable functions?" so we're in a similar place to where we were in the prior discussion.

doubtingthomas:

I can clarify the confusions in this? What you find unclear?

curi:

Do you think I was talking about "the autonomous independent idea space" earlier?

doubtingthomas:

Yes

curi:

From memory, I don't think I was. Do you have a quote where you think I was?

doubtingthomas:

You didn't say it explicitly anywhere. Do you think there exists an idea space?

curi:

Why are you asking me if I think there exists an idea space? Are you trying to change the topic?

doubtingthomas:

I am trying to approach the problem from a new position. give me some time to try to connect it. why do want everything to go your way

curi:

I don't know what you mean about wanting anything to go my way.

doubtingthomas:

How do you know I am changing the topic?

doubtingthomas:

It might be connected if you follow my train of thought

curi:

You switched from "the autonomous independent idea space" to "an idea space". It was unclear if you were trying to switch the topic or you were treating those two things as if they were the same.

doubtingthomas:

sorry for that. I considered both things to be same

curi:

I didn't say you were trying to switch the topic. I asked. When you ask how I know that you were changing the topic, it shows you misread me.

doubtingthomas:

Ok I wasn't because I said multiple times I am trying to approach the problem from a new direction

curi:

If you think idea space with three qualifiers is the same as idea space with one different qualifier, I don't know why you included extra qualifiers initially if they make no difference. That seems like a confusing error.

doubtingthomas:

I'm extremely sorry for that

If you think idea space with three qualifiers is the same as idea space with one different qualifier, I don't know why you included extra qualifiers initially if they make no difference. That seems like a confusing error.

@curi do you think there exists an autonomous independent idea space?

curi:

I don't know what the application of those qualifiers (autonomous, independent) to "idea space" means. It's not clear.

doubtingthomas:

autonomous is like it can kick back. independent is independent of human/person thoughts

curi:

i have at least one more question about each of those statements, and i wouldn't be surprised it was dozens before we were done.

doubtingthomas:

there should be

curi:

to begin with, you seem to be saying what the qualifiers mean, which isn't what i asked.

doubtingthomas:

then?

curi:

what?

doubtingthomas:

what did you wanna know?

curi:

do you see that you didn't answer my question?

curi:

not a literal, explicit question, but i brought up an issue and then you said something else instead of addressing it. what you said could perhaps be step 1 towards addressing it.

doubtingthomas:

I didn't understand the question then. Can you help me understand?

curi:

What does the application of those qualifiers (autonomous, independent) to "idea space" mean?

curi:

You said what the qualifiers mean in general, but didn't say how you think they apply to "idea space".

doubtingthomas:

got it

doubtingthomas:

i'll rephrase my question then so that this confusion doesn't come up

curi:

I'd rather you didn't. I don't want to start over.

doubtingthomas:

autonomous idea space is something that has its own objective existence. you can define integers but then the distribution of prime numbers is an independent property of it

curi:

do you have in mind an example of a non-autonomous idea space?

doubtingthomas:

idea space is a set of ideas. an idea space which consists of only defined ideas is non--utonomous

doubtingthomas:

it is dependent on the human who created it

curi:

how does the set {"bachelor = unmarried man"} depend on the humans who created it?

doubtingthomas:

he gave a word a specific meaning

doubtingthomas:

more importantly it doesn't kick back

curi:

so what? i can die and it doesn't change it. it's out of my hands. i can make false claims about it. me being the creator of that set has nothing to do with what's true about it.

doubtingthomas:

it's a definitional idea. that's why it doesn't change

doubtingthomas:

it is not autonomous because it doesn't kick back

curi:

I think this conversation is like the previous one: new issues are coming up faster than things are being clarified, so it isn't able to make forward progress.

doubtingthomas:

i've only introduced autonomous and kick back

curi:

That's incorrect, e.g. you introduced "definitional idea" and "dependent on the human who created it"

curi:

And my outstanding list of unasked questions is growing rapidly. It's gained several entries per question I did ask.

doubtingthomas:

those have their usual meaning

doubtingthomas:

And my outstanding list of unasked questions is growing rapidly. It's gained several entries per question I did ask.

@curi thus exposing our infinite ignorance I guess?

curi:

Those don't have usual meanings and I have several comments I could make about the errors involved in expecting me to know what you mean, without communication, by societal default, on a topic like this.

doubtingthomas:

please do

curi:

I don't think it's exposing infinite ignorance, I think it's exposing a discussion methodology which isn't focused on dealing with errors.

curi:

Not just discussion methodology but also thinking and learning.

doubtingthomas:

can you suggest a better alternative then?

curi:

I've researched and written at length about better alternatives. That is what some of the material in #intro and #low-error-rate is about.

curi:

I think learning typing is a good analogy. Some people type complicated words, at high speeds, with low accuracy. These errors are not primarily due to fallibility or our infinite ignorance.

curi:

The right method involves, roughly, learning the basics and prerequisites, then learning to type slowly with high accuracy, then speeding up while keep accuracy high. At no point is a high error rate necessary or desirable.

curi:

It's harder to fix errors while going fast. It's easier to fix errors in isolation, minimizing extra complicating factors.

curi:

In conversations about complex topics, people often make errors which could come up and be fixed in simpler conversations. Trying to fix them in the midst of the more complicated conversation is harder than fixing the same error in a simpler scenario. Plus then one is doing two things at once: dealing with the conversation and the error. It's easier to fix it when in practice mode without a second goal at the same time.

curi:

Same as: it's easier to improve your typing while not simultaneously writing messages to your girlfriend trying to convince her not to break up with you.

doubtingthomas:

can you tell me what will be a simpler question here

curi:

Many things, like typing or walking, can be mastered so that they no longer take much effort or attention. They become easy and you can do them on autopilot. This lets you focus your attention on other things and build on the skill (e.g. thinking about what you write while you're typing, or chewing gum while walking).

curi:

There are many levels of simplicity. E.g. grammar (parts of speech) and arithmetic are simpler things which are relevant and useful for discussing autonomous idea spaces. At a higher level, algebra and grammar (comma usage) have some relevance, though one might be able to get away with less knowledge of them.

curi:

Also, simplicity is context and hierarchy dependent. There are multiple ways to build up to a particular idea. There are different frameworks which can change how simple an idea is.

curi:

Complexity (opposite of simplicity) is related to how many parts something is composed of. There aren't privileged foundations specifying the base parts or atoms. But not all hierarchies are equal. There are some standard ones. That's something of a tangent. But lots of the things you bring up have a ton of hidden complexity.

curi:

There are many other questions I think one should consider first, like what an error is, before autonomous idea spaces.

curi:

And, to some extent, how does one managing learning, scheduling, discussion, emotions, disliking criticism, honesty and dishonesty, etc.

doubtingthomas:

error is failing to fulfill a criteria

curi:

Some of the problems in our discussion were (speculating with incomplete information) what I view as not using word-level precision. Not giving individual attention to each word used and considering its purpose and meaning. This is what ~everyone does, but I don't think it works well. It's something DD and I do differently.

curi:

"criteria" is a plural. DD told me that long ago. One can get away with some errors like that involving using words without understanding them very well, but not too many at once.

curi:

FYI ~ means "approximately"

curi:

A main objection people have to more precise thinking and writing is that it's too time consuming. This is where mastery comes in. Walking and typing can be done on autopilot. One can do the same with many skills related to writing and thinking. E.g. it can become second-nature to avoid writing "very" without an explicit reason for making an exception. One can do that automatically, by default.

doubtingthomas:

didn't godel have something to say about why perfect precision is doomed?

curi:

Probably. So did Popper.

curi:

These things are never perfect but people can do better and stop repeating the same known errors over and over.

doubtingthomas:

everything that you gave an example of has a fixed criteria according to which you can determine success. except thinking

curi:

If you change your mind about some criteria, you can change your habit to fit the new criteria. Lots of people's criteria are fairly long-lived. ~None are fixed. An actor might have to do some relearning for walking to play a part with a limp. Or some speech relearning to get control over his accent. And only recently I changed my touch typing a bit.

curi:

Adults do most of their lives on autopilot whether they like it or not. That's because their lives involve far, far more complexity than they can consciously focus on and control. A lot of errors are due to bad autopilot rather than being created with conscious attention.

doubtingthomas:

so you think I am committing that error?

curi:

Which error?

doubtingthomas:

that kind of error. autopilot kind

curi:

Everyone does it. I do think it came up in our conversation.

doubtingthomas:

so you think I don't have good enough understanding to understand the complexity of idea space?

curi:

Yes. I don't think it's close. I think most intellectuals spend most of their lives confused. I don't think e.g. Sam Harris could productively discuss it due to errors in his autopilots and autopilots he doesn't have.

doubtingthomas:

Can you clarify what you mean by "I don't think it's close"?

doubtingthomas:

my understanding to understand the complexity of idea space?

curi:

I don't think your skill and knowledge level is close to good enough. It's not a close call. I think there's a large gap.

doubtingthomas:

what should I do to cover it up?

curi:

FWIW, I say this to ~everyone.

doubtingthomas:

what should I do to cover it up?

i wanna learn

curi:

There's no realistic way it could be different, because our schools, books, and other educational institutions don't give people the tools to fix it.

doubtingthomas:

FWIW, I say this to ~everyone.

@curi i agree epistemology is the most important thing

doubtingthomas:

i wanna learn

where and how can I learn?

curi:

I've developed some options for things people can do. It depends a lot on you, what your interests are, what your skills are (you're good at some things already), what your resources are (e.g. available time and money), what you find hard or easy.

curi:

Some people are working on grammar, programming, or speedrunning video games. Most people dislike beginner stuff, and don't want to be like a child or student, but some become more open to it if they start to recognize ways other stuff is hard for them and they make lots of mistakes.

doubtingthomas:

can't I learn it through conversation in this chat with this community?

curi:

One can also just try to discuss philosophy but with an attitude of being careful and caring about small errors and trying to fix them and consider their causes.

curi:

One of the ways to do that better is by making discussion trees to help organize and understand discussions one has (or sections of discussion where problems happened).

curi:

And one can have an attitude of trying to figure out what philosophy concepts one understands with really high quality and then seeing what they imply, what can be built using them, instead of just jumping ahead to stuff one has vague ideas about.

curi:

Are you on a desktop computer?

doubtingthomas:

yeah

curi:

This is an example of a discussion tree I made recently to show someone some of the errors in a discussion. https://my.mindnode.com/nxNNJHpa1pmw2brf26ZwkWJgxWLPJAs2UxqAfHDU

doubtingthomas:

do you wanna make one together

curi:

It helps to e.g. introduce advanced or complex concepts into a discussion gradually instead of a bunch at once. One can have more respect for the difficulty of philosophy and try to break it down into smaller steps.

doubtingthomas:

It helps to e.g. introduce advanced or complex concepts into a discussion gradually instead of a bunch at once. One can have more respect for the difficulty of philosophy and try to break it down into smaller steps.

@curi that's a really good idea

curi:

Most philosophy material discourages this and encourages people to read complex stuff that they only partly understand, and to view that kinda partial understanding as success.

curi:

Schools are like that too. People pass tests, and often get A's, while not understanding stuff very well.

doubtingthomas:

true

curi:

Lots of young kids want to understand more but eventually give up on the world making sense.

doubtingthomas:

schools are the worst

curi:

Maybe we could make a tree another time. I'm leaving soon. Would have left a while ago but was interested in writing about this. Maybe someone else will. You'll find talking with other people easier in some ways (they'll tend to be more similar to you than i am, and accept more of what you say without challenging or questioning it).

curi:

I think this went well. Lots of people don't like these ideas or would be angry or upset by now.

doubtingthomas:

Maybe we could make a tree another time. I'm leaving soon. Would have left a while ago but was interested in writing about this. Maybe someone else will. You'll find talking with other people easier in some ways (they'll tend to be more similar to you than i am, and accept more of what you say without challenging or questioning it).

@curi i can see you've thought a lot about this

doubtingthomas:

Maybe we could make a tree another time. I'm leaving soon. Would have left a while ago but was interested in writing about this. Maybe someone else will. You'll find talking with other people easier in some ways (they'll tend to be more similar to you than i am, and accept more of what you say without challenging or questioning it).

@curi next time then

doubtingthomas:

I think this went well. Lots of people don't like these ideas or would be angry or upset by now.

@curi i only used the word tolerance first

curi:

Since near when I first met DD and learned about his ideas, I've been trying to figure out why most people don't understand or learn them , and why intellectual conversations, learning and debates mostly fail.

curi:

And I've been trying to expand on CR for ~10 years. CR says we learn by critical discussion but doesn't give people nearly enough guidance about how to organize a discussion.

curi:

So I have some ideas like judging every error we can find to matter a lot more than most people think it does. I find ignoring errors is a major error.

curi:

If an error is genuinely small, fix it. Shouldn't be that hard!

curi:

But we don't really know how big or small it was until after we fix it. In retrospect we may see it was small. But beforehand, we don't know how complex the solution will be because we don't yet know what the solution is. It's like predicting the future growth of knowledge.

doubtingthomas:

And I've been trying to expand on CR for ~10 years. CR says we learn by critical discussion but doesn't give people nearly enough guidance about how to organize a discussion.

@curi no one has been critical enough of these anti-rational memes. and even if they defeat those memes they don't know explicitly how they did it. so they end up giving bad advice most of the times

doubtingthomas:

yes

curi:

Like DD, I did a lot of things well intuitively, and trying to figure out what I did, so I can tell others how to do it, is something i've been working on.

doubtingthomas:

even he started to push out ideas about the fun criteria and so on. I think he is contemplating a book on irrationality

curi:

He's been contemplating that book for many years, and he's had ideas about the fun criterion for over 20 years, probably way more.

doubtingthomas:

But we don't really know how big or small it was until after we fix it. In retrospect we may see it was small. But beforehand, we don't know how complex the solution will be because we don't yet know what the solution is. It's like predicting the future growth of knowledge.

@curi because of the unpredictability of growth of knowledge we cannot have a fixed criteria against which we can judge thinking errors. that's my understanding. I can feel I am making some error here. Can you help me point it out?

curi:

fixing errors involves knowledge growth, so we don't know what the outcome will be in advance, so we don't know how long it will take, how hard it will be, or how many other ideas will have to be changed. we may estimate these things when the error is in a well understood category but there are limits, so people should be more hesitant to immediately say "that error is no big deal, why are you criticizing it?"

curi:

I think the fun criterion is bad. See http://curi.us/1882-speed-reading-is-a-core-life-skill#15609

curi:

that's a comment link. should highlight the right one. that's why the blog post title is off topic.

doubtingthomas:

yeah found it

doubtingthomas:

You said you have to leave. I don't wanna keep you. I can keep on asking questions though

curi:

You're not keeping me, I am. It's my choice. Don't worry about it.

doubtingthomas:

fixing errors involves knowledge growth, so we don't know what the outcome will be in advance, so we don't know how long it will take, how hard it will be, or how many other ideas will have to be changed. we may estimate these things when the error is in a well understood category but there are limits, so people should be more hesitant to immediately say "that error is no big deal, why are you criticizing it?"

@curi fixing error is correct. you can have a criterion for whether someone is making less errors while typing or while playing chess but you cannot implement a criteria whether someone has created a new scientific theory

doubtingthomas:

you can have that criterion only after you have that theory whether it is a new theory or not